Volume 12, Issue 2 Spring 2017

Contents of KB Journal Volume 12, Issue 2 Spring 2017

- 31869 reads

The Uses of Compulsion: Addressing Burke’s Technological Psychosis [Keynote Address]

Jodie Nicotra, University of Idaho

I'm so pleased to be here, not least because now I feel like I've come full circle with Burke and technology—writing this paper reminded me that back when I took Jack Selzer's seminar on Burke at Penn State in 2001 or so, I had initially proposed "Kenneth Burke and technology" as the topic for my seminar paper.* Jack said "eh, I don't think you want to do that. Why don't you write about Burke and this guy Korzybski instead?" Well, now I understand why he said that. I have to confess - about a third of my way into the research for this talk, I said out loud, "Why would ANYONE use Burke as a way to talk about technology?" But, as always, I'll be damned if I didn't come away understanding the human-technology relationship differently thanks to the depth of Burke's thinking about symbolic action and the function of language.

If the thinly veiled autobiographical protagonist of his short story "The Anaesthetic Revelation of Herone Liddell" was "haunted by ecology," then Burke himself was haunted by technology. Or perhaps it would be more proper to say that he was "goaded" by technology, judging by his repeated attempts to both theorize it and uncover some sort of symbolic action that might serve as a corrective. Beginning with "Waste—The Future of Prosperity," a prescient satirical essay from the late 1920s, the problem that Burke later termed the "technological psychosis" turns up again and again over the course of his career. But his later writings especially reveal what Ian Hill describes as "full apocalyptic overtones," an intensifying dread of technologically based environmental destruction that Burke, with comic ambivalence, viewed as the perfection, the logical, entelechial outcome of the rational animal's rationality.

Burke's pervasive anxiety about humanity's terrible, inevitable final goal manifests in these later works as an incessant hashing and rehashing of ideas. William Rueckert and Angelo Bonadonna characterize the Burke of the late essays as staging a "[relentless attack] on hyper-technologism" (On Human Nature 1), the essays rife with signs of his "late compulsion to refer back to earlier and other works of his, and to quote himself often" (6). Indeed, Burke himself likened his odd obsessiveness about technology to a compulsion. In one late essay, he admits to his "fixations about the problems of what I would call either 'technologism' or the 'technological psychosis'" ("Realisms, Occidental Style 105). In another he writes, "for several years I had been compulsively taking notes on the subject of technological pollution - and I still do compulsively take such notes." Burke actually loathed this compulsive note taking and longed to shut the door on the issue, "even," he wrote, "to the extent of inattention by dissipation. But it goes on nagging me" ("Why Satire" 72). If, as we can glean from reading this account, Burke took to drink in order to get shut of his obsessive attention to technology (not that he really needed that as an excuse), then certainly it must have had quite a grip on him.

Rueckert and Bonadonna suggest that Burke's obsession as it shows up in the redundancy of his later writings may have been the result of his advancing years combined with a loss of the desire to produce new work after the passing of his wife Libby. But further reading in Burke suggests that his language of compulsion in connection with technology warrants more sustained attention. Burke's own compulsions in regard to thinking about technology were also reflected in the way he talked about technology itself, to the extent that technology could be said to occupy a special third term in the nonsymbolic motion/symbolic action distinction that some scholars have marked as central to the whole of his philosophy. But more than this, I think pushing further on this idea of technology as compulsion actually suggests an avenue of response to the problem of technology as Burke sets it up. In my talk today, I want to dig a little deeper into Burke's attitudinizing of technology as compulsion and obsession; to think about what it means for Burke to characterize technology in this way, and the possibilities for action inherent in such a formulation. My talk is in two sections, the first being...

Haunted by Technology

For Burke, technology and language are deeply interconnected. In the afterword to Permanence and Change, he writes, "Technology is an ultimate direction indigenous to Bodies That Learn Language, which thereby interactively develop a realm of artificial instruments under such symbolic guidance" (296). Since for Burke as goes language, so goes technology, thinking about his treatment of one helps us understand the other. Despite his language of "instruments," Burke's depiction of the human relationship to both language and technology deeply troubles, if not reverses altogether, the typical understanding of control and agency. To wit, while the "Definition of Man" posits humans first as "symbol-using animals," reading a bit further clarifies that by this Burke doesn't mean that language is actually under our control, or that we can just use it in some instrumental fashion. He asks, "Do we simply use words, or do they not also use us? . . . An 'ideology' is like a spirit taking up its abode in a body: it makes that body hop around in certain ways: and that same body would have hopped around in different ways had a different ideology happened to inhabit it" (LSA 6). Likewise, since technology for Burke is inextricably bound up with symbol systems, he conceives of it less as an instrument than as a force that subsumes us, or at least a force that is not subject to our command.

As he suggests in the above passage, technology isn't simply neutral or passive, but has an inbuilt directionality - an "ultimate direction," to use his language. He writes, "I am but asking that we view [technology] as a kind of 'destiny,' a fulfillment of peculiarly human aptitudes" (296). Burke's mention of "destiny" and "fulfillment" here, of course, alludes to his appropriation of Aristotle's notion of entelechy; for Burke, entelechy is the "perfection" of language, such that the establishment of a particular terminology or nomenclature carries within itself its own "perfection" or inevitable end. And because of technology's inextricability from symbol systems, this entelechial drive is hence also inherent to technologies. As Burke explains in the afterword to Permanence and Change, human history has involved the turn from an early mythic orientation to what he writes is "our 'perfect' secular fulfillment in the empirical realm of symbol-guided Technology's Counter-Nature, as the human race 'progressively' (impulsively and/or compulsively) strives toward imposing its self-portraiture (with corresponding vexations) upon the realm of non-human Nature" (336). Note here Burke's language of impulsion and compulsion - the fulfillment of the technological imperative isn't just a passive happenstance of directionality, but an active drive. Thus, enmeshed in his notion of entelechy is this idea of an impetus or compelling force (i.e., something that's pushing through the perfection of symbol-guided technology). The language of compulsion, which crops up frequently in Burke's discussion of technology, appears most overtly in this passage from his satirical essay "Towards Helhaven": "Frankly, I enroll myself among those who take it for granted that the compulsiveness of man's technologic genius, as compulsively implemented by the vast compulsions of our vast technologic grid, makes for a self-perpetuating cycle quite beyond our ability to adopt any major reforms in our ways of doing things. We are happiest when we can plunge on and on" (61).

If entelechy comes from Aristotle, Burke borrows the language of compulsion from Freud, specifically the idea of the repetition compulsion developed in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. For Freud, the compulsion to repeat an originary psychic trauma across time and in differing circumstances was perhaps the most fundamental human instinct, albeit one that calls into question traditional notions of agency and freedom. Indeed, Freud suggested that the feeling of dread experienced by many people who are just beginning analysis might have its origins in the realization that they may not be as in charge of their lives as they'd like to believe. He writes, "what they are afraid of at bottom is the emergence of this compulsion with its hint of possession by some 'daemonic' power" (30).

David Sedaris's essay in the New Yorker called "Living the Fitbit Life" provides a comical, though pretty accurate portrait of such "possession by daemonic power." For those of you who don't know, a Fitbit is one of the new gadgets called "activity trackers," and it basically is like an amped-up pedometer. Sedaris writes, "To people like...me, people who are obsessive to begin with, the Fitbit is a digital trainer, perpetually egging us on. During the first few weeks that I had it, I'd return to my hotel at the end of the day, and when I discovered that I'd taken a total of, say, twelve thousand steps, I'd go out for another three thousand." His dismayed partner asks, "Why? Why isn't twelve thousand enough?" to which the narrated Sedaris replies, "Because my Fitbit thinks I can do better." Soon, the narrator finds himself walking more and more, driven by what he refers to as the "master strapped securely around my left wrist": first 25,000, then 30, 45, and finally 60,000 steps a day. He writes, "At the end of my first sixty-thousand step day, I staggered home with my flashlight knowing that I'd advance to sixty-five thousand, and that there will be no end to it until my feet snap off at the ankles. Then it'll just be my jagged bones stabbing into the soft ground."

Of course, Sedaris's description of the logical end of Fitbit wearing also happens to perfectly demonstrate Burke's definition of the entelechial function of satire, namely, "tracking down possibilities or implications to the point where the result is a kind of Utopia-in-reverse" ("Why Satire" 75). By the rationality of Sedaris's Fitbit, you must continue walking until you've worn your legs down to nibs. But while I agree with Burke that the Fitbit's symbolic framework is essential here for setting up this kind of logical end, I want to focus more specifically on the mechanisms of this compulsion. It's by the study of these mechanisms, I'll argue, that the "solution" for the technological psychosis diagnosed by Burke actually lies. To do that, I want to turn to an exchange that Burke had with Father Walter Ong, who, as you may or may not know, happened to teach at Saint Louis University for thirty years. The exchange between Burke and Ong provides some insight into the mechanisms of the technological psychosis.

This particular exchange of letters happened around an essay that Ong had sent Burke entitled "Technology Outside Us and Inside Us," in which Ong critiques instrumentalist notions of technology as "things 'out there,' in front of us and apart from us, belonging to and affecting the world outside consciousness" (190). Rather, Ong argues, we should think of how technologies also claim our insides, reorganizing our bodies through habit and reshaping our consciousness. Using the example of actual (musical) instruments, Ong points out that in learning to play, musicians must in a very material sense give themselves over to their instruments - as he writes, they "[appropriate] this machine, make it part of [themselves], [interiorize] it, gather it into the recesses of [their] consciousness" (190). Rich Doyle in Wetwares similarly articulates the human-technology relationship as a "grafting" that requires a hospitality of sorts to an inhuman form. This hospitality, writes Doyle, "relies intensely on forgetting; one must be capable of responding to the new action of a body….a capacity linked to a forgetting or an undoing of the old arcs of eye, hand, and memory" (5). In other words, we don't use technologies (including the ecologies that they come bundled with) so much as we are enticed or thrown into alliances that in return necessitate a reorganization of our bodies and our consciousness. Repeated encounters between human and technology in the light of purpose and scene prompt bodily reorganization in the form of new habits of action and perception, and new capacities. We might think of the regular user of Facebook, for instance, who starts to filter all of his experiences through the lens of their potential as written or photographic status updates; or the computer word processing program habitue, who, searching for a physical book on a shelf, finds her fingers reflexively attempting to use the Ctrl-F function; or the Fitbit user who becomes so accustomed to seeing his daily activity as the blinking dots on the device that he asks, like Sedaris, "Walking twenty-five miles, or even running up the stairs and back, suddenly seemed pointless, since, without the steps being counted and registered, what use were they?" This is more than human "use" of technology - in essence, through repeated interaction with the technology, a new virtual body has developed. And it is this virtual body, I want to suggest, that is the mechanism of the compulsion that Burke attributes to technology.

While Burke agrees with Ong's description of the mechanisms by which technology, in shaping humans, also serves as a compelling force, he still walks away from the exchange with a fatalistic view of the human-technology relationship. What he calls his "troubled attitude" in relation to Ong's essay is the fact that owing to technology's unintended byproducts (especially pollution and waste), and how much more powerful it makes individuals beyond their naked human bodies, no social or political system, no matter how full of self-consciousness, has been developed that can control "the astounding powers of technology." "Hence," he says, "mankind has a tiger by the tail." His Definition of Man reveals his lack of faith in the human ability to hang onto this tiger - he says, "The dreary likelihood is that, if we do avoid the holocaust, we shall do so mainly by bits of political patchwork here and there, with alliances falling sufficiently on the bias across one another, and thus getting sufficiently in one another's road, so there's not enough 'symmetrical perfection' among the contestants to set up the 'right' alignment and touch it off" (LSA 20). In other words, at his most pessimistic, Burke sees the technologically induced perfection of nuclear holocaust only not happening by chance.

Amplifying Obsession - Responses to Technology

Despite his anxiety about what he sees as the inevitable, terrible conclusion of the technological psychosis, Burke failed to secure a truly satisfactory solution to the problem as he defines it. As Rueckert and Bonadonna write, "Burke never developed a final vision beyond defining humans as bodies that learn language, establishing the link between language (symbol systems) and technology, and determining that technology was our entelechy" (272). Judging from the number of apocalypse narratives that currently populate screen, novel, and newspaper, there are many who would agree with Burke's fatalistic vision about the inevitable tragically perfect end of humanity's current rationally guided course. But I want to suggest that in Burke's very language of entelechy and irresistible compulsion there is a compelling framework for "solving" the problem of technology.

Because for Burke the human relationship with technology was thoroughly bound up with language, symbolic action was therefore the thing necessary to adequately address it. But what kind of symbolic action is the question. Perhaps because for Burke technology is so rooted in the idea of entelechy, both Burke and his critics assume that what is necessary to address the technological psychosis is a symbolic corrective - i.e., something that could serve to block or put the brakes on technology lest it continue rolling along to its disastrous finale of environmental apocalypse. James Chesebro summarizes the essence of this view in his argument that rhetorical critics must adopt a "decisively skeptical" role when it comes to the symbolic constructions of technology; everything must be put on hold until "dramatists have determined how a symbolic perspective can be used to counter technology" (279).

For some, such a corrective could only be grounded in human consciousness. Even Rueckert and Bonadonna, glossing Burke's take on the technological psychosis, fall into the consciousness trap. In their introduction to one of Burke's late essays, they write, "What you have at the 'end of the line' is a vast human tragedy which might have been averted if humans had paid heed to their own knowledge of what more and more technology might bring. We are not talking about pollution here, but about foreknowledge and the ability or failure to act on it. The other factor is the failure to foresee the consequences of an action or development" (4). With the language of knowledge and foreknowledge, we might hear in Rueckert's summary echoes of Ong's faith in human consciousness as the thing that might protect us from technology's disastrous consequences and preserve human freedom - that if we just knew enough or had enough knowledge about an issue, we could rationally discuss it and come up with a solution. Indeed, raising awareness about technologically induced environmental problems is what many environmentalists rely on to spur the public to action. But it's clear from even a cursory glance at the landscape of current public opinion and legislative wranglings over science and technology that mere awareness of problems (or even the provision of mountains of information and evidence) ultimately matters very little when it comes to decision-making or policy creation about environmental matters like, say, climate change.

Using tactics that are more recognizably Burkeian, T.N.Thompson and A .J. Palmeri recommend that rhetorical critics and dramatists develop what they call a "poetic psychosis" in order to counter Counternature. Psychotic poets would, they say, "exercise the resources and range of symbols, giving wings to 'agitating thoughts' so that they might enlist the action of others" (280), in countering technology. They write, ominously, "Poetic and comic correctives are needed to counter the rapid mutation of counternature before it reaches the 'end of the line' - its perfection - where the merger of mind and machine will leave no need for a poem" (283). But while I like this idea of fighting psychosis with psychosis, I still want to call into question the author's frame of rejection of technology here. [Problem with saying no - does Burke say anything about this in his ideas of the negative?.]

Satire was Burke's own solution for correcting the technological psychosis. As he explained in the essay "Archetype and Entelechy," satire can help reveal the terminological choices that lead to entelechies, but in a way that provides different possibilities for action. He writes, "satire can so change the rules that we have a quite different out. The satirist can set up a situation whereby his text can ironically advocate the very ills that are depressing us - nay more, he can 'perfect' his presentation by a fantastic rationale that calls for still more of the maladjustments now besetting us" (133). Burke employed this symbolic strategy of amplification in both his earliest satire on technology "Waste - The Future of Prosperity" and one of his final ones, "Towards Helhaven." With tongue in cheek, Burke suggests in the early essay that rather than people maximally waste in order to better the economy. He improves upon this amplification strategy in "Towards Helhaven" by "recommending" an action proposed by a certain gentleman who suggested that if a lake has been polluted, rather than turning backward or countering this action by asking how to undo or mitigate the destruction, to rather "affirmatively" address the issue by continuing to maximally pollute the lake, ten times as much - thereby, Burke writes, either converting it to a new form of energy or "as raw material for some new kind of poison, usable either as a pesticide or to protect against unwholesome political ideas" (61). The image is bitterly hilarious.

But even though Burke's approach to satire works mechanically by amplifying or pushing a particular notion through to its logical end, it still ultimately (as Thompson and Palmeri point out) is a frame of rejection. It hopes to counter technology, to say "no" to it. But, using Burke's notion of satire as a cue, what if we were to think of a form of symbolic action that uses this same strategy of amplification as a frame of acceptance - one that says "yes" rather than "no"? I want to suggest Burke's own concept of technology as irresistible compulsion as a candidate for this idea of amplification or pushing through. In other words, we might take the final words of the Helhaven essay - "No negativism. We want AFFIRMATION - TOWARDS HELHAVEN" (65) more seriously than Burke meant them - perhaps not in a directly material, technological sense, like adding maximal pollutants to a lake, but in a symbolic sense, whereby we amplify the concept of compulsion to its logical conclusion, by thinking of technology as a compulsion over which we have no control. What if we literally could not help ourselves when it came to technology? That we had to, as Burke says, "perpetually tinker" until we blew up the world or sank ourselves in a horrific miasma of pollution from which only the lucky rich few could escape? How could we use this very idea of compulsion not as a corrective to technology, but as a way to push it through? If nomenclatures, as Burke argues in his essay "Archetype and Entelechy," are formative, or creative, in the sense that they affect the nature of our observations, by turning our attention in this direction rather than that, and by having implicit in them ways of dividing up a field of inquiry" (Dramatism and Development 33), then naming and treating technology as a compulsion will reveal certain possibilities for responding, and foreclose others.

Consider, for instance, the range of responses by environmentalists to the problem of climate change, a convergence of factors that Burke would certainly have read as the moment before the apocalypse. Most mainstream environmentalist approaches - a perfect example being Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth - rely on maximizing consciousness about climate change, the inherent assumption being that if people just understood or had enough information about the problem, they would change their behavior and their voting strategies. And while there's certainly nothing wrong with attempting to combat misinformation, one only needs to do a quick survey of the majority of Western attitudes to see that even if people have the "correct" information, it doesn't mean they'll automatically change their behavior or even their beliefs, thanks to factors like identification. (Along similar lines, X has an excellent article showing how, despite mountains of evidence for evolution, creationists still refuse to believe it).

Far more interesting approaches to the problem of climate change, I think, are those that amplify the idea of technology as compulsion by literally metaphorizing the Western relationship to oil as an addiction. Rather than setting up a frame of rejection, as do the strategies that rely on maximum consciousness, amplifications using the metaphor of oil addiction turn the attention affirmatively toward particular kinds of solutions. Those who adopt the nomenclature of oil as addiction can (to use more traditional rhetorical terminology), argue at the stasis of policy rather than fact or definition. They bring different sets of questions into play - like what is the most effective way to treat an addiction? For instance, Larry Lapide, the Research Director of MIT's Supply Chain Management 2020 initiative, argues that most American supply chains are "addicted to oil." The oil-as-addiction metaphor allows Lapide to move past arguments about whether there is a problem and who caused it to more pragmatic issues like identifying the most oil-heavy aspects of supply chains and encouraging businesses to analyze their own supply chains in order to make themselves less dependent on the fraught resource of oil. Lapide actually relies on a sort of petroleum-based Pascalian wager, recommending what he calls a "no regrets" risk management strategy when it comes to oil - namely, "Decrease your supply chain's dependence on oil to make it less vulnerable to price increases and supply chain disruptions." ("Is Your Supply Chain").

An even more interesting example is the Transition Network, an organization aiming to respond to the realities of climate change that was designed from the beginning around the concept that Western society is literally addicted to oil - in fact, the subtitle of The Transition Handbook, a bible of sorts for those who want to start a "Transition Initiative," is "From oil dependency to local resilience." In its pragmatic materials for guiding towns and other areas begin what Transition refers to as an "energy descent," lessening their dependence on oil, the Transition Network is grounded in metaphors of addiction. Arguing that generally speaking "the environmental movement has failed to engage people on a large scale in the process of change," (84), Rob Hopkins writes in the Transition Handbook that it is critical to understand how change actually happens, which led him to a model well known to addiction psychology called the Transtheoretical Change Model. The "Stages of Change," as the TTM model is popularly known, identifies a number of stages (like pre-contemplation, or the awareness of the need to change, through action, and maintenance) that addicts incrementally move through in treating their addiction. According to advocates of this addiction treatment model, understanding which stage one is in offers opportunities for understanding what might be blocking change (or, conversely, what pitfalls one needs to be aware of in the treatment of one's addiction). In applying this model to entities beyond an individual, Hopkins encourages potential Transition Initiatives to think of themselves as addicts and (like the supply chains above) apply the model to understand the specific nature of their dependence. As Hopkins says, "Recognising oil dependence makes it easier to understand why it might be difficult to wean ourselves off our oil habit, while also joining us towards proven strategies from the addictions field that might help us move forward" (87). A strategy of information—a strategy that says "yes."

Owing to his own tragic vision of technology, Burke ultimately could only view it through a frame of rejection. But while his writings specifically having to do with technology may not themselves offer to a productive response to technology, considered in a broader context - especially in terms of technology's enmeshment with language and all that entails in a Burkean sense, I find that they offer a way of thinking around the back door of technology, but one that says Yes rather than No, that affirms attitudes and hence pushes actions. Of course, I'm not suggesting that thinking of oil as addiction (or technology as compulsion) is the answer to all our environmental problems. But the general notion of looking for strategies of affirmation. I'll end here with an idea from Guattari that speaks to how I think Burke would have wanted to see technology were it not for this peculiar blind spot.

"This new logic - and I wish to stress this point - has affinities with that of the artist, who may be induced to refashion an entire piece of work after the intrusion of some accidental detail, a petty incident which suddenly deflects the project from its initial trajectory, diverting if from what may well have been a clearly formulated vision of its eventual shape. There is a proverb which says that 'the exception proves the rule'; but the exception can also inflect the rule, or even re-create it" (140).

The assignment according to Guattari is figuring out how to "promote a true ecology of the phantasm - one that works through transference, translation, the redeployment of the materials of expression - rather than endlessly invoking great moral principles to mobilize mechanisms of censure and contention" (141).

* This is an unrevised version of a keynote address at the Triennial Conference of the Kenneth Burke Society hosted at Saint Louis University in 2014. The revised version, "The Uses of Compulsion: Rewriting Burke's Technological Psychosis as a Posthuman Program," appears in Ambiguous Bodies: Kenneth Burke and Posthumanism, edited by Christopher Mays, Nathaniel Rivers, and Kellie Sharp-Hoskins. Penn State University Press.

Works Cited

Burke, Kenneth. "Waste, or the Future of Prosperity." The New Republic 63 (1930), 228-31. Print.

—. Language as Symbolic Action. Berkeley: U of California P, 1966.

—. "The Anaesthetic Revelation of Herone Liddell." The Complete White Oxen and Other Stories. U of California P, 1968. 255-310. Print.

—. "Towards Helhaven: Three Stages of a Vision." The Sewanee Review 79:1 (1971), 11-25. JSTOR. 20 Jan 2014.

—. Dramatism and Development. Worcester, MA: Clark UP, 1972. Print.

—. "(Nonsymbolic) Motion/(Symbolic) Action. Critical Inquiry 4:4 (1978), 809-838. JSTOR. Web. 16 Jan 2014.

—. Letter to Walter Ong. 9 September 1978. Walter Ong Papers. St. Louis University.

—. "Afterword: In Retrospective Prospect." Permanence and Change. U of California P, 1984. 295- 336. Print.

—. "Archetype and Entelechy." On Human Nature : A Gathering While Everything Flows, 1967-1984. Ed. William Rueckert, and Angelo Bonadonna. Berkeley: U of California P, 2003. 121-138. Print.

—. "Realisms, Occidental Style." On Human Nature: A Gathering While Everything Flows, 1967-1984. Ed. William Rueckert, and Angelo Bonadonna. Berkeley: U of California P, 2003. 96-119. Print.

—. "Why Satire, With a Plan for Writing One." On Human Nature: A Gathering While Everything Flows, 1967-1984. Ed. William Rueckert, and Angelo Bonadonna. Berkeley: U of California P, 2003. 66-95. Print.

Chesebro, James W. "Preface." Extensions of the Burkeian System. Ed. James W. Chesebro, Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 1993. vii-xxi.

Doyle, Richard. Wetwares: Experiments in Postvital Living. U of Minnesota P, 2003. Print.

Freud, Sigmund. Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Tr. [from the German]. Bantam, 1959. Print.

Guattari, Felix. "The Three Ecologies." Trans. Chris Turner. new formations 8 (1989). Web. 30 May 2014.

Hill, Ian. "'The Human Barnyard' and Kenneth Burke's Philosophy of Technology." KB Journal 5.2 (2009). Web. 03 Jan 2014.

Hopkins, Rob. The Transition Handbook: From Oil Dependency to Local Resilience. Green, 2008. Print.

Lapide, Larry. "Is Your Supply Chain Addicted to Oil?" Supply Chain Management Review 11.1 (2007). ProQuest. Web. 06 Jun 2014.

Ong, Walter. "Technology Inside Us and Outside Us." Faith and Contexts. Ed. Thomas J. Farrell and Paul A. Soukup. Atlanta: Scholars, 1992. 189-208. Print.

Rueckert, William and Angelo Bonadonna. "Introduction." On Human Nature: A Gathering While Everything Flows, 1967-1984. Ed. William Rueckert, and Angelo Bonadonna. Berkeley: U of California P, 2003. Print.

Sedaris, David. "Stepping Out." The New Yorker 30 Jun 2014. Web.

Thompson, T. N., and A. J. Palmieri. "Attitudes toward Counternature (with Notes on Nurturing a Poetic Psychosis)." Extensions of the Burkeian System. Ed. James W. Chesebro. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 1993. Print.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

- 19912 reads

Technological Devolution, Social Innovation: Attitudes Toward Industry

M. Elizabeth Weiser, The Ohio State University

Weep not that the world changes—did it keep /A stable changeless state, 'twere cause indeed to weep. —William Cullen Bryant

Abstract

Technology changes our identity, with the same ambiguous results Burke saw evidence of all around him eighty years ago.1 His reaction was to counsel caution, even repudiation, but his dialectical rhetoric and comic corrective offer a more nuanced theoretical approach to the ambiguous conversation between humans and technology. His theories point toward a means to replace both his extreme distrust of technology and industrial communities' previous naïve optimism with an active, critical shrewdness.

AS IAN HILL NOTES IN KB JOURNAL, "Because [Kenneth] Burke's theory of rhetoric is so intertwined with bodily survival and the technological threat thereto . . . Burke's critical program embodies a technological rhetoric." But his attitude is not friendly, Hill goes on: "Burke's observations of technology again and again emphasized its destructive capacity."

Rhetorical communication today, in contrast, with its emphasis on digital media analysis and production, oftentimes embodies a different sort of attitude. To paraphrase Bob Dylan, it is more like "better get out of the new world if you can't learn to code—for the times, they are a-changin'." Like so many, I teach my students to use the technology of the 21st century in a Rust Belt town bruised and battered by the technology of the 20th. So should our conversation with technology be one of praise or blame? Changing our viewpoint from the tragic to the comic frame makes it clearer that it is both. Technology has always been a-changin' our identity, with results more ambiguous, more akin to the love-hate relationship Burke saw evidence of all around him 80 years ago. His reaction—in his writing and his life—was to counsel caution, even at times repudiation, but his dialectical rhetoric and comic corrective offer a more nuanced theoretical approach to the ambiguous conversation between humans and technology. His theories point toward a means to replace both his extreme distrust of technology and industrial communities' previous naïve optimism with an active, critical shrewdness.

Because I study identity formation in museums, I became particularly interested in the potential manner in which this shrewdness was dramatized in museums in former industrial centers like my town. How do communities which thrived through technology, whose identity was based on their relationship to technology, narrate the story of their betrayal when that technological identity is lost? The experience of industrial museums in depicting the ambiguous human-technological relationship yields useful insights as we in post-industrial settings face the need to re-orient our perspectives.

In this brief article I compare two similar industrial museums—both named "Work"—in two similar industrial boom-bust-cautious recovery towns: Newark, Ohio (where I teach) and Norrköping, Sweden (where I worked while on sabbatical). I also look at the new industrial exhibits in the National Museum of American History, perhaps the first exhibits in any national museum to focus specifically on the business side of technological innovation. I examine museums because their epideictic frame is more likely to provide the space and time to consider multiple voices in debate, a hallmark of the comic frame. Through their promotion of a communal identity, they may also prompt visitors to engage as Agents in their world. I argue that Burke's interminable conversation in the comic frame, in a Scene which has the potential to promote identification with a polyvocal community, which has never been so important as now, as humanity continues "on the edge of the abyss" in a rapidly technifying world (Burke, "Anaesthetic Revelation" 296). Without recourse to an identity as Agents, communities facing industrial change as a tragedy become fatalistic and despairing, see heroes and villains rather than co-workers, invent scapegoats and strongmen, long for the past rather than challenging the future—in short, they become the "heartland" electorate that rose up in the last election in populist revolt against a changing nation. Changing the narrative that forms their identity is no mere aesthetic exercise, then, but a real-world exigence.

Before examining specific museum exhibits, let me acknowledge the ongoing conversations in museum studies over the degree to which any museum exhibit is memory rather than history, story rather than truth; as well as questions of whose memory/history/story/truth is recounted and to what effect. These are important questions, but leaving them aside in this article, I will instead focus on the effects of the narratives told by the exhibits, adopting Burke's pragmatic social constructivism that acknowledges both the viability of multiple perspectives and the recalcitrant nature of "reality": It exists, and it sets bounds on the ways the past can be portrayed and the future envisioned. As Edward Schiappa writes in a piece comparing Burke's master tropes and Thomas Kuhn's scientific paradigm shifts, "Despite the potential cries of relativism against both, neither Kuhn nor Burke meant that people can 'see' anything they want" in our metaphor-infused world "because, as Burke noted, 'the universe displays various orders of recalcitrance' to our interpretations, and we are forced to amend our interpretations accordingly. Thus, our perceptions have an 'objective validity' (PC 256-57, qtd. in Schiappa). It is not that museum exhibits and the communities they serve cannot shape the story, it is that the material objects, the communal memories, the larger sociopolitical context, and even the generic characteristics of narrative itself all set bounds on just how the shaping will occur—and it is the shaping and its consequences I examine in this article.

As Hill notes, Burke's concern with technology was due in part to its role in heightening people's natural reluctance to change in response to changing circumstances because "although capable of communicating, machines lack the poetic sensibility to react to changing conditions with altered symbolism." Human motivation is understandable but not rational, as Burke insisted repeatedly as a counter to his positivistic age—it is shot through with attitudes while "the technological machine [is] the external expression of the rational ideal" (Burke, "Literature and Science" 160). Technology, like the science that develops it, pushes the human toward that "rational ideal," but the human condition recalcitrantly refuses. Thus, wrote Burke in this 1937 address to the Third American Writers Congress, "I think that the restricted concept of scientific style is not adequate to name human motivations. I doubt whether references to 'causality' will ever 'explain' choice; they can only chart limitations of choice" (163). For Burke, it is the artist who sees beyond the strictures imposed by current expected connections to make new connections. These new juxtapositions, new ways of looking at a situation, are what allow people to move beyond an entrenched mindset—in this case, to see themselves as more than the cogs in a machine (particularly if that machine is now failing). Whether a given museum allows the needed juxtapositions into its narrative can mean the difference between a community asserting itself as a change Agent in the conversation with technology and a community struggling to do so, as we shall see.

The Towns

Newark, Ohio, pop. 48,000, and Norrköping, Sweden, pop. 87,000, are surprisingly similar. Both were home to prehistoric native communities which left important archaeological remains that both towns, until recently, have largely ignored. Both towns took advantage of their strategic transportation opportunities—rivers and railroads—to become proud engines of the Industrial Age during the 18th to 20th centuries. As a Norrköping pamphlet explains, "Several hundred years ago a number of factories were built along the river Strömmen. Imposing factory buildings took shape, providing many of the inhabitants with work producing textiles, weapons, paper and electronics. Norrköping was a flourishing industrial city for many generations" (Upplev Norrköping). Newark, meanwhile, was a stop on the Ohio & Erie Canal, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and the National Road. Even today, Interstate 70, with its stream of semis delivering products back and forth across the country, runs just a few minutes south of town. By the 20th century Newark was the world's leading manufacturer of stoves and interurban cars, and its glass manufacturing, from Coke bottles to fiberglass, made it an important supplier in the global network. Large factory complexes dot its landscape. In the mid-20th century, Norrköping was called "Little Manchester"; Newark was "Little Chicago."

Clearly, the two towns' similarities are due in part to their integral roles in the industrial machine. As Burke noted in Attitudes Toward History, "We use the term 'world empire' with relation to technology because technology's vast and ever-changing variety of requirements means in effect that areas hitherto widely separated in place and culture are integrally brought together" (20). Both Norrköping and Newark utilized similar resources and locations to build powerful identities linking themselves to the global marketplace during the height of the Industrial Age, and with similar results. Beginning in mid-century, however, both towns suffered the effects of deindustrialization from automation and globalized competition. Little by little for the next forty years, the factories and mills shut down, thousands of people were thrown out of work, and the sense of identity in both towns suffered tremendous dislocation that continued through the turn of the new century. This was the destructive industrial force—or at least one of the destructive forces—that Burke saw as inherently threatening. The analogy Burke used in a 1974 article explaining his aversion to industrial technology was that "the driver drives the car, but the traffic drives the driver" ("Why Satire" 311)—that is, individuals are buffeted by the social force of the tools they supposedly control. Certainly this is what happened to the people of both Newark and Norrköping.

Out of this common industrial devolution, both towns opened museums devoted to their industrial legacy.

The Works Museum

The Works Museum, in Newark (hereafter the Newark Museum), was founded in the former Scheidler Machine Works, a 100-year old factory beside the mass of railroad lines and canal just south of the downtown courthouse square. Most of the museum, which attracts an audience mainly of local schoolchildren and their parents/grandparents, is oriented toward its ground floor science center, and the museum focuses the majority of its programming on science education and the returning small visitors who "play" in the center. But the reason the science center exists is because Newark identifies itself as a longstanding hub of technology, and that history is depicted on its much-less visited upper floor. One-third of this second-story space is devoted to the settlement and growth of the town into a "manufacturing city" during the19th century. Another third features volunteer-staffed "living history" displays from the era. A final third, "Manufacturing in Licking County," attempts to encapsulate the 20th century. Here are vitrines of self-contained displays from some dozen or so of Newark's key 20th century industries: Pure Oil, Rugg Lawn Mowers, Burke Golf Clubs, Wehrle Stoves, Heisey Glassware, Jewett Interurban Cars, Park National Bank, Holophane Lighting, Owens Corning Fiberglass.

Figure 1. Image of the Works Museum, Newark, Ohio, showing some of its historical exhibits of Newark industries. Photograph by the author.

More than half of the companies exhibited are now closed, and most of the others have seen significant local workforce reductions. The human impact on the workers of this dramatic change is only hinted at: "The Heisey Company closed its doors for Christmas vacation in 1957 and never re-opened." "In 1971 the Burke line moved to Morton Grove, Illinois." "By 1966 the plant was sold to the Roper Company." "The Jewett company declared bankruptcy in 1918 and never recovered." "What changes will take place in the 21st century?" asks the sign that closes the history section. Many of those changes have already occurred from the post-war industrial peak— the percentage of people in poverty in the County has nearly doubled in the first 15 years of the new century (Ohio Development Services Agency Research Office)—but that story is largely absent. Absent as well, then, is a dialogue on contemporary or future Newark.

What is this if not a Burkean terministic screen, the symbolic reflection of reality that by its very nature must be a selection of reality that must function also as a deflection of reality? Hill writes of technologists choosing terms that "select beneficial technological artifacts as argumentative proof of progress" thereby deflecting their "destructive reality." At the Newark Museum, the "proof of progress" that is selected is the glory that was, the technological achievements of an earlier era. The destructive reality that is deflected, therefore, is the human cost of the business cycles rendering many of these accomplishments obsolete. The company went bankrupt, the factory moved to Mexico, the business was sold to others . . . but what does this mean for the town? Because the Newark story focuses terministically on technology, it must spend its epideictic capital on praise alone—praise for the growing manufacturing might of the town, praise for the transportation channels, praise for the innovators who made technological advances and the entrepreneurs who opened factories; praise, then, for the factories themselves. If it were to epideictically blame anything, it would have to call into question the very advances—and advancers—that it is designed to praise.2

It is this gap in the selected conversation that the Arbetets Museum in Norrköping attempts to address.

The Museum of Work

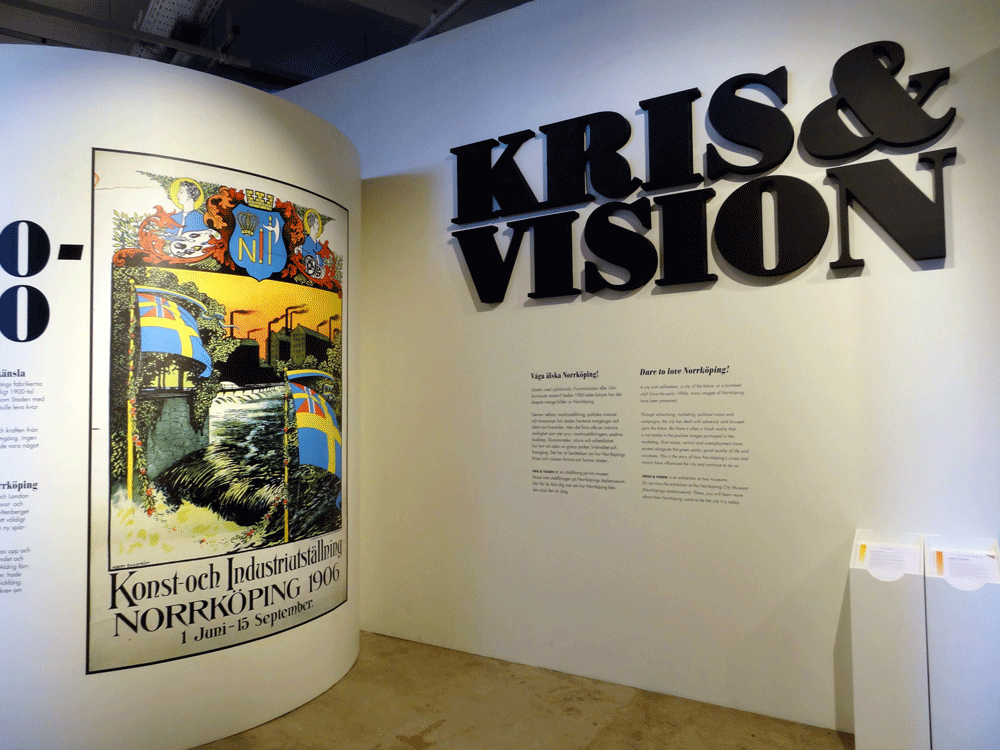

The Arbetets—which means "Work" in Swedish, thus the Museum of Work—is housed in a former textile mill, and like Newark's The Works, it attracts a largely local audience of families, students, and retirees, with a smattering of tourists. Like Newark, the Norrköping Museum emphasizes upfront the educational fun of its children's science center. The historical aspects of Norrköping industry, meanwhile, are found next door in the Stadsmuseum (Norrköping City Museum), which includes a large section of textile mill and a "street" of 19th century tradesmen (cooper, cartwright, blacksmith, cobbler, tailor). So far this is not dissimilar to the Newark Museum, and from 2012-15 an exhibit of 20th-21st century history, displayed jointly in the two museums, echoed the post-war "Manufacturing in Licking County" exhibit as well. The synopsis for this exhibit, "Crisis and Vision: Dare to Love Norrköping," however, immediately makes it clear that the exhibit is more than epideictic praise for the glorious past. As it explains, "[h]istorically, the city of Norrköping has experienced both great successes as well as immense failures both of which have left their mark on the city and its inhabitants. What can we learn from these crises and visions and how will the city look in the future?" ("Facts about the Exhibition").

Figure 2. Image of the Arbetets Museum, Norrköping, Sweden, showing the entrance to its multi-year exhibition "Crisis and Vision." Photograph by the author.

With its mix of epideictic praise and blame for the communal values on display throughout Norrköping's 20th-21st century iterations, the exhibit wades directly into a conversation that would be familiar across the industrial rust belt: "What happened, and what will we do now?" Like Newark, Norrköping in the first half of the 20th century billed itself as "The City with Self-Esteem." Like Newark, its signage reports that it had transportation, "amazing gear-driven technology," and "skilled, low-paid workers." It is here that the "work life" orientation of the Norrköping Museum comes forth, however, as the exhibit goes on to add that "factory work at this time was low paid, dirty, noisy, and dangerous." While the Newark Museum mentions that post-war life was faster paced, the Crisis and Vision exhibit notes that that fast-paced life also meant that "The work tempo was increased and breaks were shortened." Industry was good for Norrköping—but not only good. Yet it was also not only bad. There are many examples of civic pride in the successful town. When textile mills began closing in the 1950s-60s, then, as the exhibit goes on to narrate, Norrköping struggled to respond. In its self-identified "City of Tomorrow" of the 1960s, it first attempted diversified industry and tourism. In the 1980s, "A Friendly Town" welcomed government agencies and demolished block after block of the old 19th century worker apartments. The exhibit shows a photo of the bright modern worker apartments that replaced the slums, but it also discusses the epithet resulting from this demolition—"The Bombed City." "The bleak 1990s" threw thousands more out of work, yet the exhibit also displays promotional videos from the period touting the pleasures of Norrköping for both tourists and businesses.

Looking to the Present

In the 2000s, the area around the Norrköping Museum has seen its sprawling, shuttered factories revitalized and turned into a college campus branch, a science park for new knowledge-based industries, shops, concert hall, and tourist office, all linked by pedestrian/bike pathways along the rejuvenated river in "The City of Knowledge and Culture."

The area around the Newark Museum is also revitalizing, with its 19th century courthouse and jail now deemed "historic" and marked for renovation, its closed movie and ballroom "palaces" turned into live concert venues, its square made pedestrian-friendly, its paved-over canal transformed into a covered Farmer's Market, and, slowly, ugly streetscapes turning into inviting areas. Industrial technology is also making new inroads into the county at large, with new companies moving in, taking advantage once again of the central location. Unemployment is down to 3.8% as of this writing, one of the lowest in the state (Williams).

At the same time, both towns face a continuing problem of poor health, low education, and un- (or under-) employment among their poorest residents. The workers that new industries need are dozens of highly skilled engineers and technicians, not the thousands of low-skilled line workers of decades past. This ambiguous recent development is documented in the Norrköping Museum exhibit, but not at the Newark Museum, where the epideictic praise-display upholding the value of Newark's past industrial greatness closes off the narrative from critique, and therefore from the possibility of discussing an ambiguous present. In contrast, the final sign in the Norrköping exhibit not only lays out the data on current successes and failures, it also encourages audiences to actively consider their impact and identify with the town: "Today, a lot of hard work is being done to create an attractive image of Norrköping. But the reality is more complicated. What is your view of Norrköping?" In a more dialectical world, people are the Agents in the conversation.

Assigning the Agents

What is it about the Norrköping Museum that allows it to engage visitors in the ongoing technology-driven changes outside its doors in a way that the Newark Museum cannot?

First, the mission statement of the Norrköping Museum focuses on people in dialogue, not industrial success. The Norrköping Museum's mission is "to document working life and bring its history to life through: providing a forum for debate and interpretation of the working lives and conditions of women and men" ("About the Museum"). Though this is similar to the mission statement of the Newark Museum, which aims to be "an interactive learning center where people of all ages can have fun and be inspired by the history, technology and artistic accomplishments of the communities we serve" ("About the Works"), there are two fundamental differences. One is the terministic screen through which the museums examine the role of industry in their communities. The Newark Museum adds to its mission statement an origin narrative noting that its founder "assembled a group of local citizens interested in preserving Licking County's industrial past" ("About the Works"). That is, preservation of industry was the impetus for the museum. Both museums recognize that workers and technology are the two components of industry, but the terministic screen for Norrköping—the linguistic lens with which it names its world—focuses on the workers ("working life") while that for Newark focuses on the technology ("industrial past"). Not surprisingly, then, the Norrköping Museum includes a number of social commentary exhibits among its rotating collections, such as the "Industrial Country—Sweden in the Modern Age" exhibit when I was there in 2012; "Job Circus," whose goal was both to help young people explore careers of the future and explain causes of the skills mismatch in 2014; or their recent "Land of Tomorrow," an exhibit that is "meant to be a tool box and source of inspiration for discussions and thoughts about a future that is sustainable – ecologically, economically and socially" ("Current Exhibitions"). That is, the Norrköping Museum uses its exhibits to re-orient its audiences from a late-century perception of themselves as (failing) industrial giants by posing critical questions designed to encourage thinking not so much about the technology itself but about the city's reaction to it, and their continuing reaction. The Newark Museum, in contrast, is more trapped in the past. It might, with its terministic screen of technology, add extant industries to its display cases, but by focusing on technologies rather than people its narrative can only relate the next industrial success rather than the ongoing town actions/reactions. Thus, its two industrial exhibits in the past few years have (1) added a display case on communication that "encourages all to examine how the cell phone has changed their own life and the world" ("History Exhibits"); and (2) housed a temporary exhibit on the history of glass-making, focusing on praising the post-war innovations of mid-century giants Owens Corning and Holophane, two companies that have downsized and closed in the county, respectively, in the past 10 years.

The difference in their terministic screen (industrial past or working life), in turn, affects to whom they assign the pentadic role of Agent in the dramatic conversation between human and technology. Newarkians should love Newark because it has been great. This terministic choice, however, in combination with its necessary focus on decades-old history, has consequences not only for the narrative but also for the current communal identity of the narrative's audience. To Newarkians today—to the 21 percent below the poverty line, for instance (Ohio Development Services)—"it has been great" is neither a current reality nor a future promise with which they can personally identify. The possible responses to this narrative of past industrial greatness are only passive: People can despair that the greatness is gone or they can wait for it to return (and hope it touches them). In this light, even the vote for a demagogue who promises to "Make America Great Again" is in the end a passive gesture—a shot in the dark that someone with the authority of industry can make bring back the past for them. In all cases, it is industro-technology which is the acting Agent, the one in the driver's seat, not humanity.

In contrast, the Norrköping Museum narrative is not one of industrial greatness but of industrial greatness and corresponding humanitarian difficulties. Its focus on working life means that its epideictic narrative can both praise workplaces for their industrious innovation and blame them for working conditions, pay, etc. Focusing on the social means focusing on the town, in other words, and the town can advance and retreat and (ambiguously) advance again. This is a narrative not of greatness but of resilience, and innovative Agents are not only technological but also social—perhaps most importantly social. Burke thought this focus on sociability to be key to understanding human motivation. Humans, he thought, were best explained not by their role as individuals who happened to join into groups, but as primarily political beings, "a context of definition whereby his individual role is defined by his membership in a group" ("Literature and Science" 165). It is through their identification as social/political beings that humans find themselves, Burke thought, not vice-versa, and therefore a focus on social resilience is in essence an appeal to human nature. Norrköpingers are encouraged by the museum narrative's praise and blame of the ongoing social history to identify with this ongoing social resilience of the town itself, and this calls for a more active response than that of Newark. It is a response that promotes ongoing cooperative innovation. To put it another way, residents of Norrköping are encouraged by the narration of their past century to become participating Agents in the succession of challenges and successes brought by technology to their town, while residents of Newark are prompted by the narrative to see their historic role as passive Agencies who may (or may not) be used by the industrial Agents that are changing the town today.

The Comic Corrective, the Industrial Past, and the Critical Present

Burke's America in the late 1930s was a time not wholly unlike our own. The disruptions and hardships of the Depression dragged on, war grew more and more imminent, and the bright promise of technology to make lives better that was so keen in early decades of the century grew increasingly muddied by its human consequences. Despite widespread struggle and the specter of worse, however, people did not rise up and embrace structural change—and Burke struggled in articles and books to understand why not. As he put it his 1937 piece for the Third American Writers' Congress, "[I]f we do learn by analogy, if we do form our response to new situations on the basis of what we have learned from past situations, it would seem to follow that we must, to an extent, be hypnotized by a past situation while confronting a new one" ("Literature and Science" 169). Technology was the rational outcome of the rational mind—and if the rationality that produced the very technology creating such new situations could only lead to continuing down the same path, regardless of human desire for other choices (the traffic driving the driver) then some way of perceiving the situation that was less purely rational was a needed corrective. As I've written about elsewhere (see Weiser, Burke, War, Words), it was the New Critical way of looking at old situations, exploring juxtapositions and paradoxes, embracing ambiguity, all so much a part of the modernist poetry of the early 20th century, that was Burke's model of the "sharp sound that awakens us [from our hypnosis], at times when the rise of new materials requires us to shake off an old perspective and to frame a wider circle of correctives" ("Literature and Science" 171). That is, the solution to "technosis," the kind of rational technological perspective that would lead to misery and war, was not more of the same but something different, a new, wider frame of reference enabled by a conscious reframing from inevitable tragedy to Agent-driven comedy.

To return to Burke's technological conundrum, does the fast-paced world in which so much of society finds itself, with technological advances that drive the driver, benefit society or threaten it? Although in Burke's 20th century those in power largely answered "benefit" and Burke therefore focused on "threaten," a Burkean comic frame would instead answer "yes." Yes, it does both, but—as was evident at the recent global climate summit—it is humans, not machines, who have the potential agility to adapt their conversation with technology to reflect changing Scenes and the shrewdness to continue the dialogue. Burke's stated view on technology seems so decidedly negative—as he sums up in "Why Satire," a relentless drive toward industrial technology produces waste, war, and pollution—that it seems too hopeless, of little use in forming an adequate conversation of "words about words about technology." For in fact Burke's view was rarely hopeless, and he both acknowledges the extremes of his perspective and offers a possible way out via what he termed from the beginning of his career the comic corrective (see Attitudes Toward History). While in a dramatic tragedy it is only through human suffering that catharsis is achieved, he noted, within the comic frame difficulties are not viewed as evils but as mistakes—and mistakes can be fixed. Thus Burke's explanation for the differences between the reactions to past greatness and ongoing resilience would be that the people of Newark are asked by their own industrial narrative to place themselves in the frame of a technological tragedy, invoking heroes and villains (then deflecting from the perceived villainy), while the people of Norrköping can place themselves within the frame of a social comedy, with its cast of fools, and then act to fix mistakes made earlier.

The outcome of the former is inevitable, that of the latter is a work in progress; thus, the tragic frame, Burke acknowledged, does not really offer a true perspective on the technological world.

Though the present developments of technological enterprise . . . have led to the affliction of much suffering, and raise many threats, the technologically experimental attitude behind all such activities is not in spirit tragic. So far as I can see, the technological impulse to keep on perpetually tinkering with things could not be tragic unless or until men became resigned to the likelihood that they may be fatally and inexorably driven to keep on perpetually tinkering with things. . . . Also, I keep uneasily coming back to the thought that, with the cult of tragedy, maybe you're asking for it. ("Why Satire" 312)

The technological impulse does not, in fact, lie in the hero-or-villain arena of tragedy unless we resign ourselves to its inevitability—whether that inevitability is the wasteful destruction of the planet or the technotopia of a brave new world. Thus pure indictment as surely as pure praise of our technological identity merely reduces our role as Agents in our own conversation.

The comic frame is the escape from the passive resignation or disengagement of such either-or thinking. "The comic frame of acceptance," he wrote in Attitudes toward History, "considers a human life as a project in 'composition,' where the poet works with the materials of social relationships" (173). As Burke had discussed in Permanence and Change, much social interaction tends toward stagnation rather than action—it was either wholly "euphemistic," upholding the status quo, or wholly "debunking," tearing down the existing structure (166). The comic attitude toward social interaction, in contrast, is neither overly sentimental—a nostalgic remembrance of better times—nor overly shocked when faced with the betrayal of those good times. It is instead a "shrewd but charitable" view toward one's opponents, one that acknowledges the possibility of betrayal even while continuing to engage, "picturing people not as vicious, but as mistaken. When you add that people are necessarily mistaken, that all people are exposed to situations in which they must act as fools, that every insight contains its own special kind of blindness, you complete the comic circle" (ATH 41). This shrewdness is what allows for social interaction rather than withdrawal— in interpersonal relationships as much as in political parlays and social dynamics. We might build an industrial empire only to lose it all and throw thousands out of work, we might pin our hopes on an industrial savior only to see it move to a cheaper labor market, we might try to clear out the slums and make better housing for all only to look like we've bombed our own city, we might better our lives through technology only to realize it is destroying the planet . . . and then, if properly primed by narratives of past engagements in similar dire moments, we might keep on trying. Notice again the Norrköping Museum's "Land of Tomorrow" exhibit: In a "future that takes the threat of climate change seriously," "what can you or I do?" it asks. Improving the conversation with technology—which is both part of the problem and part of the solution—is key to that future.

The comic frame, therefore, is not only a corrective to an overly rational historic hypnosis, not only a pragmatic solution. In its ambiguous perspective, its acknowledgment that there are multiple cuts of cheese even as one's own looks best, it is also the best way to converse with technology because technology itself is an ambiguous conversant, neither villain nor hero. At times technology is the Agency or tool, the thing made by our industrial genius; at times the Action, the interactive exploration of our innovative selves; oftentimes it is the problematic Scene, the context within which industrial cities like Newark and Norrköping forge their communal identity; other times it is the Purpose, its perfection the entelechial end goal of our actions regardless of the human consequences. As hero or villain or fool, it can appear also as the co-Agent with us humans, acting on us even as we act on it. The comic frame, though, reminds us that we humans are also always Agents in this drama, needing to act and react to the ongoing conversation with technology.

The National Museum of American History

To demonstrate a bit of this comic frame enacted in a cultural scene, let us look at one other museum, the National Museum of American History (hereafter National Museum) in Washington, DC. Unlike Sweden's national museum—indeed, unlike any of the 25 other nations' museums that I examine in my forthcoming monograph Museum Rhetoric—the U.S. National Museum has two permanent exhibits (opened in July 2015) expressly devoted to industrial entrepreneurship and business innovation. To what extent does the comic frame exist in the narratives of these two exhibits? How is ambiguity acknowledged, and who are the Agents in this industrial scene—people or technology?

The more technologically focused exhibit, "Places of Invention," uses a tripartite narrative frame of people, place, invention to tell the stories of six American regions where technological innovation occurred. "What kind of place stimulates creative minds and sparks invention and innovation?" asks its introductory sign. "See what can happen when the right mix of inventive people, untapped resources, and inspiring surroundings come together." In dramatistic terms, particular groups of Agents paired with particular Scenes and Agencies enabled an innovate Act moving the nation into the modern world. So for instance, Stanford, sunny weather, and a "casual but fiercely entrepreneurial business climate" lured tech workers who eventually banded together as "academic, corporate, and hobbyist communities [to] invent the personal computer" in Silicon Valley. These simple, monologic praise narratives are openly family-friendly, not meant for in-depth critical thought. Its exhibits, however, do walk a line between our two local "Works" museums by assigning agency to people and places in conversation to produce technology. That is, if the dot.com bust, gender equality, or privacy issues are not discussed in the Silicon Valley section, neither are the silicon chip nor Ed Wozniak given sole credit for personal computing. Collaboration, the narrative tells us, was the key to the invention—and what better way to materialize Burke's dramatistic contention that in any symbolic action the Act, Agent, Agency, Scene, Purpose overlap, none of them complete without the others, because "we are capable of but partial acts, acts that but partially represent us and that produce but partial transformations" (GM 19). The comic ambiguity of these partial acts-interacting is the essence of how invention occurs in the "Places of Invention" story.

This partial biographical agency given to communities of people interacting in places is continued in the narrative of the other new permanent exhibit, "American Enterprise," just across the hall. The intended audience for this exhibit is clearly older, more educated, and more willing to take the time to contemplate than the audience for Places of Invention. Thus artifacts are musealized in vitrines with a variety of signage offering both casual and in-depth reading, but the attitude of knowledge-production is not necessarily equated with one solo Truth. Instead, American enterprise in this exhibit moves by fits and starts, sometimes taking a wrong path only to course-correct later, generally moving toward increased industrialization but always within a scene of ongoing debate over whether this movement is necessarily "progress." The exhibit moves chronologically and divides US industrial history into four epochs: the Merchant Era, Corporate Era, Consumer Era, and Global Era. Each section tells its story from a variety of perspectives, making overt for the visitor those multiple cuts of cheese that, as Burke insisted, would make it easier to view one's own cut as just one possibility. For instance, in the Merchant Era visitors learn about business in the early years of the nation from the stories of Metis fur traders, Eli Whitney, shopkeeper William Ramsey, weaver Peter Stauffer, and stories of electricity, slavery, debt, gold, and land grabs.

As we can see already, the frame of the exhibit allows for the inclusion of a number of "mistakes" in the entrepreneurial path, from slavery to (later) the annexation of Hawai'i, the Dust Bowl, and consumer debt. Rather than a tragic frame that insists on either epideictic praise or blame, the comic frame of the exhibit allows for both/and in the interaction between human and technology. For example, it notes that with digital technology, "immediate access to everything helped spawn a social media revolution, gave consumers greater choices, and sped up business. Some loved being connected, but others worried that they could never escape work or surveillance." The artifacts accompanying this ambiguous signage also sometimes support the narrative of praise and sometimes that of blame. Thus, accompanying the digital technology sign is a radial display of all the types of devices (phone, watch, camera, map, computer) that are now contained in one smartphone—a praise display. But accompanying the signage on globalization, which tells us that "in a globalized economy, innovative ideas and products flowed easily across national borders," a more ambiguous display includes a Japanese McDonald's sign, a Walmart truck, and a Disney shirt, raising questions about the kinds of "innovations" flowing across the world. And a vitrine discussing green business practices, which notes that at first "companies responded with empty public relations campaigns" and only later saw the potential for profit, accompanies this statement with photos almost exclusively of people, rather than technology, acting to promote change for a more sustainable future. Within a comic frame these human Agents interacting with technology need not be pure in their motivations nor produce wholly praiseworthy results in order to proceed. Indeed, the history of wrong turns included in the entrepreneurial story lessens the need to imagine that such future-forward acts as digital media, globalization, and sustainable energy must be already resolved as good (or bad). In the comic frame, where tragic absolutism turns to comic potentiality, they may well be good and bad.

Figure 3. An image of the National Museum of American History, Washington, DC, showing the diversity of perspectives in its display of industrial eras. Photograph by the author.

At the end of each of the four industrial eras, signage "Debating Enterprise" sums up the intended comic frame of the exhibit…. and Alexander Hamilton debate whether government should promote industry at all or should encourage farming to grow the new nation. (Admittedly, these "differing voices" are nearly exclusively male, a weakness of their selection.) The visitor may infer that the question of how to balance government and business for the benefit of the nation has been the predominant debate of American enterprise—and it is a debate at best unresolved and perhaps unresolvable. That as readers of this article we may feel strongly that there is, in fact, a proper balance that, almost certainly, the nation has not achieved demonstrates our propensity to embrace the tragic frame of right and wrong, good and evil. The comic frame opts instead for the ambiguous answer between Agents whose varying positions are not considered evil but at most mistaken, and partially foolish, capable of persuading/being persuaded.

Conclusion: Symbolic Engagement

In his presentation at the 9th triennial Burke conference, Jimmy Butts argued that for Burke it would be the end of the conversation that would be the real tragedy. Butts began with Burke's interest in the word "apocalypse," which (like substance, another favorite Burkean word) has a paradoxical meaning. From its Latin root, kalypto, we get "eclipse," a covering of the sun; adding apo- or "away from" gives us the "apocalypse"—so the cataclysmic end-time is literally an unconcealing or unveiling, "a revelation of the truth," says Butts. For Burke the end of the world as we know it, the entelechial stasis would be the revelation of some ultimate truth that ended the interminable conversation that is "always decentering" (Butts). Such a revelation of truth is often a desired goal—including a goal of visitors to a museum, who want to hear the one true story—but Butts points out that for Burke it is the ever-ongoing conversation that keeps us from apocalypse. The end of the debate is stasis, and in any living organism stasis equals death.

As is evident in today's spiral of rancorous, ad hominem attacks, most of us do wish for an end to the always decentering dialectic whenever we debate opponents with strongly held beliefs. Surely the giant industrial complex of the 20th century either was, in truth, heroic or was, in truth, demonic. It is well to remember that in Burke's definition of the human, homo dialecticus, the creature who "by nature respond[s] to symbols" (Burke, RM 43), is also homo technologicus, "separated from his natural condition by instruments of his own making" (On Symbols and Society 70). What industrial museums and exhibits offer to the polarized world of homo technologicus, then, is a way to poetically interact with alienated (and alienating) technology. Recall Hill's insight that Burke's concern with technology was that it impeded change because unlike humans "machines lack the poetic sensibility to react to changing conditions with altered symbolism." The comic frame of a narrated exhibit can bring the human visitor into conversation with her own inventions—be they a full-scale turn-of-the-century machine workshop (Newark) or automated looms producing real woolen items (Norrköping) or the knick-knack-filled workshop of the inventor of Pong (National). They remind us materially of the relationship between humanity and technology. Though this can potentially be a mere nostalgia trap, the museal equivalent of "make America great again," it can also engage us in the narrative. And narrated as a heuristic for a community seeking agency, this engagement with the comic past of trial and error and trial again is an argument to move from the disempowering search for heroes and villains. As the National Museum asks visitors repeatedly, "What would you do?" This is the question not of victims of a tragic past but of citizens of an ever-struggling (ever-striving) future.

Notes

1. A version of this article was presented as a conference paper at the 9th Kenneth Burke Society Triennial Conference, July 2014. I am indebted to James Zappen's 2014 presentation at the Triennial Conference for the idea of this human-technology interaction as a "conversation" and a relationship, as well as his gracious reading of an earlier draft of this article. I am also grateful for the insightful comments of the KB Journal reviewer whose advice better focused the final draft.

2. Newark's newest permanent exhibit does highlight a person—local resident Jerrie Mock, who in 1964 became the first woman to fly solo around the world—but visitors are asked to imagine being her ("test your skills at a flight simulator"), rather than being asked, for instance, to consider how we in Newark today teach or learn the skills to become first in the world in a field.

Works Cited

Arbetets Museum. "About the Museum." n.d. Web. 2 Aug 2014.

—. "Current Exhibitions." 2015. Web. 13 December 2015.

—. "Facts about the Exhibition." Norrköping, Sweden, n.d. Print.

Burke, Kenneth. "The Anaesthetic Revelation of Herone Liddell." The Complete White Oxen: Collected Short Fiction. Berkeley: U of California P, 1968. 255-300. Print.

—. Attitudes Toward History. 3rd rev. ed. 1937. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print.

—. Counter-Statement.1931. Berkeley, CA: U of California P, 1968. Print.

—. On Symbols and Society. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1989. Print.

—. Permanence and Change. 1935. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print.

—. "The Relation between Literature and Science." Henry Hart, ed. The Writer in a Changing World. New York: Equinox Cooperative Press, 1937. 158-71. Print.

—. A Rhetoric of Motives. 1950. Berkeley: U of California P, 1968. Print.

—. "Why Satire, With a Plan for Writing One." Michigan Quarterly Review 13.4 (1974): 307-37. PDF.

Butts, Jimmy. "How Burke Wanted to Save Us from Our Techno-Apocalypse." 9th Triennial Conference of the Kenneth Burke Society. St. Louis, MO, 19 July 2014. Presentation.

Hill, Ian. "'The Human Barnyard' and Kenneth Burke's Philosophy of Technology." KB Journal 5.2 (2009). Web. 1 Aug 2014.

Ohio Development Services Agency Research Office. The Ohio Poverty Report. Columbus, OH, 2014. PDF.

Schiappa, Edward. "Burkean Tropes and Kuhnian Science: A Social Constructionist Perspective on Language and Reality." JAC 2.13 (1993). Web.

The Works: Ohio Center for History, Art, and Technology. "About the Works." 2014. Web. 2 Aug 2014.