Embodied Rhetorics: Writing Rides from the Seat of a Bike

Janice Chernekoff, Kutztown University of Pennsylvania

Abstract

This essay connects Burke’s concept of a mind-body dialectic with studies of embodied rhetorics to explore connections between bodily vocations and the writing linked to them. Randonneuring, a form of endurance bicycling, and the ride reports written by participants, provides a case in point.

Introduction

I remember Roc’h Trevezel as the name of an endless climb at the end of an endless night.

As I climb in the blue gray light that comes before the dawn, I notice the crucifixes that appear along the road like distance markers. Each one unique but appearing regularly along the road we ride.

I remember climbing a steady moderate grade from one crucifixion scene to the next. As I ride past these potent symbols of sacrifice and redemption, these stations of the cross, I realize that I am on my own secular pilgrimage: [I am] one of many who have come from afar to visit a place that only exists for a moment, to share a transformational experience created by the faith, sacrifice and effort of many.

Tired and weak, I approach the peak of Roc’h Trevezel. Then the sun rises and reveals the world to me. The peak is not a peak as much as a plateau. The lower peaks of the valley are islands afloat above the low-lying clouds. (Greene 18)

Like pilgrims embarking on the five-hundred-mile Camino de Santiago walk in Spain, randonneurs come to France once every four years to attempt the seven-hundred-fifty-mile Paris-Brest-Paris (PBP). In the passage above, Nigel Greene, having completed the 2015 PBP in under ninety hours (the time allowed for an official finish), characterizes his attempt as a “secular pilgrimage” requiring “faith” and “sacrifice” to succeed. PBP is the equivalent of Mecca for randonneurs, long-distance cyclists in a French tradition established more than a century ago.¹ The ride report is also a well-established tradition: riders describe preparing for an event, the trials and tests encountered during the event, and the lessons learned from it. News reports from initial editions of PBP, as well as ride reports by cyclists from the UK, Australia, Canada and the U. S. essentially take the same form. This is a stable genre because the riding and the writing are connected in ways that point to the “chemical sort of rhetoric” that Debra Hawhee says Kenneth Burke locates in his study of endocrinology (Moving Bodies 86). The ride report is a deeply human expression of material rhetoric, a response to an embodied rhetorical situation, such that the genre of the response and its enduring nature can be explained using Burke’s concept of the mind-body experience (Burke P&C 229).

Rhetorical Bodies

We should take seriously the embodied rhetoric of which we are constituted and the genres it manifests. I use “embodied rhetoric” literally, building on Burke’s mind-body term that he argues is a way of signifying the material basis for human symbolic behavior; all symbolic behavior, according to Burke, “is grounded in biological conditions” (P&C 275). Burke adds that this is not to suggest that rhetorical behavior is reducible to biology (P&C 275), but that human bodies are the kind of bodies that learn language (P&C 307). Other scholars have also worked to clarify this productive term and what it allows us to consider regarding rhetoric. Hui Niu Wilcox, for example, writes that embodied knowledges are revealed and expressed through “lived experiences, cultural performance, and bodily intelligence” (106), a view that brings attention to the rhetorical intelligence of bodies at the level of muscle and bone. A. Abby Knoblauch as well says that embodied knowledge is “knowing something through the body” (52), which is another way of saying that at least some of what we know and the way in which we express it emerges from the inextricably linked mind and body. The ride report and similar kinds of stories — for example, the stories of long-distance trail runners, marathon runners, ironman triathletes, and other endurance athletes — provide concrete instances of embodied rhetoric, supporting my claim that while genres generally respond to changes in “audience and circumstance” (Schryer 208), and are consequently only temporarily stable at best (Schryer 204), the ride report melds riding and writing into a more enduring genre that evidences a symbolic dialogue regarding an enduring human rhetorical situation.

Recent scholarship on embodied rhetoric builds on Burke’s arguments and extends them into other fields, providing convincing examples of materially embodied rhetoric. Jack Selzer claims that Celeste Condit, for example, uses DNA coding to model “how material rhetoric might be understood to incorporate both gross physical corporeality and the social and material act of ‘coding’” (13). Condit, who claims that Burke can usefully be thought of as “an idiosyncratic American post-structuralist (Brock)” (331), argues that “language as used by human beings does not operate without regard to the material realm, [so] it is better to say that language users constitute objects out of matter/form relationships, or, more technically, that language essentializes (by selection and identification) material/form patterns and relationships into perceived objects” (332–33). Condit sees Burke’s relevance to contemporary discussions of material and embodied rhetoric and relies on Burke to argue that rhetoric emerges from “complex and shifting material/energy/relationships” (333). Embodied rhetoric engages human energy as generated within the body and expressed in language forms appropriate to the experience. Jay Dolmage approaches the issue through the lens of disability studies, arguing that, “our own and our students’ bodily differences [are] meaningful and meaning-making” (“‘Breathe Upon Us’” 119). In support of his argument, Dolmage discusses the Greek God Hephaestus whose disability, Dolmage argues, was his ability, informing his intelligence and his way of seeing the world (122). The various disciplinary approaches to embodied rhetoric demonstrates the idea that bodies and bodily energies interpolate discourse. As Debra Hawhee notes about Burke, his “engagement with bodies from a variety of disciplinary vantage points foregrounds the body as a vital, connective, mobile, and transformational force, a force that exceeds — even as it bends and bends with — discourse” (Moving Bodies 7). If the body is a rhetorical agent, what does the body prompt us to ask and explore? And what are the effects of experience on genre, on forms of discourse?

Rhetorical Riding and Writing

Bodily questions inspire rhetorical responses that inform and create intelligence. The question of how far we can push ourselves physically is one bodily question that has inspired not only randonneurs, but a wide range of endurance athletes as well as religious pilgrims who walk the Camino de Santiago or fast for extended periods or engage in other activities that take them out of their physical comfort zone. To a significant degree, it is the body that experiences the question, endures the trials, and experiences the answers to the question. It makes sense, then, that the writing about such experiences will have a similar form; the experience influences the form of the reflection on it. Not every person is an endurance athlete or religious pilgrim, but people who are ask some of the same questions. How far can I go? What will I learn by pushing my body and mind to the limit? What are the limits? Endurance runner Kilian Jornet, who has completed ultra-distance races world-wide writes, “I want to challenge myself, give the best of myself, and try to discover what my thresholds are, to know myself better” (153). Jornet is inspired by bodily exigencies that involve pushing himself to his limits in order to comprehend and physically live the responses to the mind-body questions. Endurance sports athlete Rebecca Rusch similarly claims that accepting physical challenges helps us define ourselves. She writes that “every moment is an opportunity to outlast and overcome the odds that threaten to either paralyze us or tether us to fear and doubt. The moments when we endure define us and mold us into the people we want to be, as athletes, leaders, or partners” (270). According to Rusch, taking up these bodily-generated questions is critical to who we are, how we act, and what we think. Brian Crable’s analysis of Burke’s ideas on bodily rhetoric echo the arguments of the above athletes. Crable writes,

According to Burke, the foundation of human existence is organic — we are embodied, which means that certain permanent needs and ‘purposes’ cannot be denied. Further, these needs and purposes, which drive our earliest behavior, form the foundation for symbolic activity; sociality, with both ideal and material/economic dimensions, is a biological outgrowth. At the same time, the symbolic realm that is thereby constituted is not reducible to biology. (123)

Some of these permanent needs and purposes underlie all symbolic behavior, according to Crable, but they also form the basis for enduring genres; patterns in symbolic responses may not be biological but the patterns respond to and satisfy biologically inspired rhetorical exigencies.

One feature of ride reports, indeed of many stories about physical challenges, is an explanation of how and why the writer accepted the challenge. People less athletically inclined may think that randonneurs are crazy to ride long distances in rain, without sleep, or over mountains, but even randonneurs feel the need to understand and explain why they undertake these challenges. The explanations point to a faith — a secular faith — not only in the ability of body and mind to overcome hardship, but also in the rightness of taking on the adventure. In the epigraph to this essay, a piece titled “Living the Dream,” Greene notes that PBP is a “transformational experience created by the faith, sacrifice and effort of many” (18). Randonneurs who train and show up for PBP do so in part because they accept that it is a good and human thing to show up for this 750-mile ride, no matter the results. Indeed, all along the route of PBP, local people come out to support riders with food, drink, music, and places to rest; so spectators in France also see the value in the efforts of the riders. And the riders hope (and have faith) that the mind and body will work together to make success possible, but even if the adventure goes awry, they will emerge more fully the human beings that they want to be. Long-time randonneur Laurent Chambard, writing about another 750-mile ride, The Gold Rush Randonnée through more remote areas of Northern California, explains his reasons for wanting to attempt this epic ride:

The Gold Rush Randonnée (GRR) has been on my list of targets for a good while. I find the description of the ride . . . simply fascinating. The promise of 1200km of cycling through some of the last unspoilt parts of California, in what was once Gold Rush country, and over a route where altitude varies from sea level to nearly 2000 metres [6500 feet], has left me dreaming over the map a good few times.

Chambard embraces the challenges presented by the “unspoilt” parts of Northern California in a ride that includes mountains, heat, desert, lack of shade, and long stretches without any services. Chambard dreamed of doing this ride, his mind and body, even in his sleep, wondering if he was up to the challenge.

Randonneurs often frame their induction into randonneuring, and especially an interest in PBP, in quasireligious terms, indicating the depth of their feelings about and commitment to their sport. In a 1975 PBP ride report, American Harriet Fell explains how she became interested in randonneuring when French work colleagues convinced her to extend her limits and accompany them on a two-hundred-kilometer ride, a distance that she had done once before so she was “willing to give it a try.” Her description of the ride includes the fact that they started before dawn on a day with “terrible, freezing rain.” The weather was so terrible that “Marvelous crystalline structures formed on the beards of [her] friends.” She notes that she was a lot faster after lunch and that the group finished together “in eleven hours and ten minutes.” Fell’s description of this ride, which amounts to her introduction to randonneuring, shows her pride in having faced physical and mental hardships with success — so much so that she agreed to ride a three-hundred-kilometer ride with these same colleagues a few weeks later. Also visible in this story, as with Chambard’s story, is an orientation to the world that includes a desire for challenges. Fell acknowledges that what they are doing is a little crazy, but she is pleased to find that she can endure, despite the “crystalline structures” on her friends’ beards, and despite the fact that she had only once before covered this type of distance. Sacrifice and faith: two key terms in religion, appear frequently in ride reports as well as in the stories of other endurance athletes signifying the importance to them of these activities.

A disposition for challenges may be viewed as an orientation or bias toward the world, and according to Burke, a disposition has biological roots:

Our calling has its roots in the biological, and our biological demands are clearly implicit in the universal texture. To live is to have a vocation, and to have a vocation is to have an ethics or scheme of values, and to have a scheme of values is to have a point of view, and to have a point of view is to have a prejudice or bias which will motivate and color our choice of means. (P&C 256–57)

If we embody vocations and related biases, and those predispositions affect our interpretations of events, including how we frame them, it is not hard to understand that endurance cyclists have written similar stories about their adventures since the inaugural running of the Paris-Brest-Paris. After all, the creation of this event was simply another iteration of a vocation or set of values embodied by some people. An endurance cyclist is likely to seek out, see and understand the experiences of, not only other endurance cyclists but also other endurance athletes as inspirational, while someone with a different orientation to the world might view these people as a little wacky. In another 2015 PBP ride report, Bob Hayssen recalls signing on for a 2014 200-kilometer ride “on a whim.” During the ride, there was much anticipatory talk of PBP 2015. Hayssen says that “it sounded like a great adventure. I was quickly hooked” (16). Hayssen already embodied the values required for endurance cycling when he was introduced to randonneuring; that is, he was predisposed not only to do PBP but to write the ride report he wrote before he signed up for the event. Condit argues that a fully materialist view of language “recognizes both the reality of forces in the universe and the way in which motivated human action objectifies those forces through language into more or less durable relationships with more or less intensive presence and visibility” (334). Some “motivated human action” is intense, deeply engaging the body and mind together in satisfying and durable relationships. Burke explains that our minds select certain linguistic concepts or relationships as purposeful, and that these “relationships are not realities, but interpretations of reality” (P&C 35). I’ve been arguing that such is the case with ride reports, and these “relationships” are visible in the way that ride reports are written. Additionally, some of the writing actually mimics bodies in motion (on bicycles).

The rhetorical intelligence of the body posited by scholars such as Hawhee and Jennifer LeMesurier is evident in writing about riding in which the author attempts to use language to describe the mind-body experiences of riding a bike over long distances. The problem is always, as Bryan Crable points out, identifying and characterizing the nonsymbolic “from within symbolicity” (126). However, in the following passage by French cyclist and writer Paul Fournel, he captures well the ineffable connection between cells, muscles, mind and words, and how the rhetoric of maximum effort can be circulated throughout the body:

I can’t determine precisely the instant in which my thought escapes its object to become a thought of pure effort. The moment the rhythm speeds up, the moment the slope becomes steep, the moment fatigue gets the upper hand, thought doesn’t fade away before the ‘animal spirits’; on the contrary, it’s reinforced and diffused throughout my entire body, becoming thigh-thought, back-intelligence, calf-wit. This unconscious transformation is beyond me, and I only become aware of it much later, when the lion’s share of the effort is over and thought flows back, returning to what is ordinarily considered its place. (128–29)

Fournel argues that during intense physical effort, “thought” flows through one’s entire body, so that the body — thighs, back, calves — takes control, and only later, after the physical effort has been completed, does thinking become primarily an activity of the mind. Even then, while the mind may seem to control thought, the memories and knowledge of the physical effort completed are stored in the body. The body, writes LeMesurier, is “a conduit for remembered knowledge” (363). In the middle of an intense activity, the body often seems to take the lead; indeed, athletes interested in improving performance train until the moves or actions that they expect of their bodies are “automatic.” It is as if the training and the experience makes one into the kind of person — in both body and mind — who does the kind of activity for which one is training.

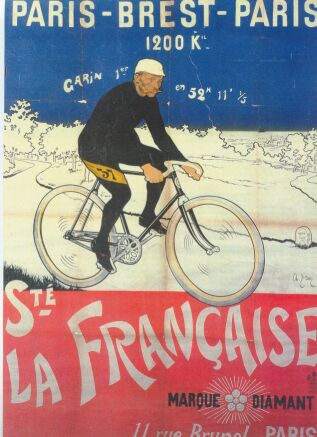

Figure 1. Featured in the poster is Maurice Garin, winner of the 1901 Paris-Brest-Paris as well as the inaugural Tour de France in 1903.

Shaping and reshaping the body and mind through repetition and a focus on rhythm was practiced by the Sophists, according to Hawhee. She writes that they used rhythmic gymnastic exercises, repetition of movement and music to train young rhetors properly (“Bodily Pedagogies” 147). According to Hawhee, the Sophists believed that “the forces (people, music, movement) one subjects oneself to will necessarily shape and reshape body and soul” (“Bodily Pedagogies” 152–53). It may also be true then, that a body and mind intensely trained to particular rhythms will seek them out, see them in experiences, and finally express them in language. Endurance cyclists experience most obviously the rhythms of turning wheels and pedals. They also experience the cycles of preparing for, doing, and then resting from intense physical efforts. In the following passage, Christine Newman effectively uses repetition of the phrase “I learned” to suggest the need to keep pedaling, even through pain and deep fatigue, to finish her ride:

I learned that mental toughness will allow you to ride for 300+ miles with two knees that are begging you to stop. I learned to pick the food which fills you up and keeps you going even if you can’t stand the sight of it after three days. Ninety miles from the finish, I learned that it is possible to be more tired than you have ever been in your life, so tired that you cannot stand up let alone ride a bicycle safely. I learned that I could fall asleep, in spite of a deep panic that my ride would fail not due to a lack of training but from a lack of sleep. (22)

In this description of the last part of her 2011 PBP ride, Newman uses the phrase “I learned” four times in as many sentences; the rhythm of the sentences suggests the rhythm of pedaling. While she tries to describe how she was feeling, Newman also tries to structure her sentences to suggest her meaning. Quite literally, this writing is embodied in the sense that Hui Niu Wilcox is referring to when she writes that embodied knowledges are revealed and expressed through “lived experiences, cultural performance, and bodily intelligence” (106). Newman’s lived ride experience is materially linked to her writing about it; her experience is written in, on and about her body, with the ride report being her best effort to reflect that experience.

Newman and Fournel, quoted above, also implicitly suggest that they engage in endurance cycling events because they anticipate that a tough ride, like PBP, will force them to function in a way that combines mind and body beyond logic and daily thought. The cycle and rhythm of such rides (or similar events) may then become familiar, and those wonderfully challenging moments may become something that one craves. That is, the process of an event can be ritualized, much as a religious ceremony, with each aspect of the ceremony holding meaning for the celebrant. Particularly in the writing of riders who have done events like PBP more than once, there is anticipation as well as the embodied knowledge of what it is required, and this is reflected in the way a person speaks and writes about the event. The ride and telling the story of the ride constitute a vocation in the sense that Burke uses this word — one’s “ethics or scheme of values” infuses one’s being as well as one’s speaking and writing. Lois Springsteen, who has completed PBP seven times so far, anticipates the event with joyful memories, with hopes for a decent performance in the next iteration of the event, and an eagerness for the wash of experiences that PBP brings. After the 2015 PBP, she reflects:

But why go back? It’s hard to describe the wonderful feel of PBP. At times it is more a festival than a grueling challenge. Cheering crowds and street parties, bicycle art, impromptu roadside coffee/snack stands abound. There were six thousand cyclists on this special, quadrennial 1230K/ 90 hour pilgrimage with red taillights glowing as far as one could see during that first night. While I have not ridden many other 1200K randonnées, I will venture to say that this one is the most unique of all due to the sheer number of participants. Even though I have become one of the oldest female riders, I still wanted to be part of it. (9)

Springsteen returns to PBP and writes about her experiences because she yearns for this familiar “pilgrimage.” Physically and mentally, rhetorically, Springsteen responds to the PBP call with the same questions that prompted her to show up for her first PBP thirty years ago. Can I complete this ride again? What will I learn this time? Now, the call elicits a response from her at the level of what Hawhee calls “learning-performing” memories (“Rhetorics” 156). Being tuned into a set of patterns and rhythms provides comforting familiarity as well as purpose in our work to understand and more deeply embrace our lives.

For many randonneurs, the ride report is the last part of the cycle of the event, providing an opportunity to reflect on one’s experiences and convert them into words, for oneself and to share with others. The ride report effectively transubstantiates the body-mind experience of the ride into a narrative that typically pays close attention to the call to ride, the ride and the difficulties endured, and the redemption earned through the ride. The report, that is, follows the contours of a spiritual body-mind experience. Vickie Tyer, in a middle section of her 2015 PBP ride report, illustrates the difficulties riders have when they begin to deal with sleep deprivation and fatigue. She describes the need to “dig deep” to make it through a second sleepless night to get to Brest according to her plan: “The skies got foggy, and the night got chilly and lonely. I had to dig deeper. I was determined to see Brest before sunrise, no matter what” (15). While the phrase “dig deeper” is typically used as a metaphor, here it is intended almost literally, as if her mind and muscles together are reaching deeper into her being for the willpower to keep turning the pedals. The end of her ride report describes the finish: “ . . . then I was crossing the finish line, with a crowd of wonderful people cheering for little ‘ole me. What a blast. What a sense of accomplishment. What redemption. What a ride. Words cannot describe it.” (15, emphasis added). I take Tyer literally. I think she did struggle to put into words the “learning-performing” memory — the sense of release — stored in her body by her PBP experience. The redemption earned completes the cycle and the narrative, written for herself and shared with others, allows people with the same set of values to see how they, too, might earn a similar sense of satisfaction. Ride reports like Tyer’s cause me to search within myself for the courage and will to attempt this ride, and I know that narratives like this may initiate similar forms of action and thought in others. I agree with Hawhee that there is a “curious syncretism between athletics and rhetoric” (Hawhee, “Bodily Pedagogies” 144), and this amalgamation of bodily matters with rhetoric inspirits body-mind journeys.

Endurance cycling, including randonneuring, is a vocation by Burke’s definition for Tyer and many others. Devotion to this vocation is deep and enduring because its adherents clearly see their experiences as spiritual, judging by the language and metaphors of ride reports. Piety is the attitude of a vocation; Burke notes that, “Where you discern the symptoms of great devotion to any kind of endeavor, you are in the realm of piety” (83). I would add that when we are operating in the realm of piety, we are by definition thinking and acting in a realm that is to some degree beyond language. As noted, Tyer is literally stumbling for words in the above passage to describe aspects of her experience. In a 1995 issue of Australia’s randonneuring magazine, Checkpoint, the editors also reference this phenomenon: “Many of the stories that found their way into Checkpoint over the past year reflected the self-confessed amazement by ordinary folk who actually achieved incredible feats. Little do they realize that they are capable of (sic), and some will attend PBP in 1999” (3). Awe and wonder, feelings associated with experiences that cannot be put into words infuse the attitude present in many ride reports. Writers are often amazed by their accomplishments; Australian Trevor King’s 1999 PBP report tells of his discovery after returning home that he had fractured his pubic bone during a fall, and that he had completed the last nine hundred kilometers with this injury (12). American Lois Springsteen writes in her 2015 PBP report of finishing the last forty miles with a broken wrist (8), and British journalist J. B. Wadley, in his 1971 ride report, writes about riding through mind-numbing and hallucination-creating fatigue. Finally, from a short 1921 Le Mirroir des Sports article comes this short quote from Louis Mottiat, winner of the event that year²: “I wanted to sleep, I felt bad sitting on my saddle, and I was thirsty, but I stayed strong” (trans. mine). A vocation is a calling or a mission that textures one’s life and gives it meaning. In the experiences summarized above, the rider-writers use available language and a familiar form to articulate transformative moments in life.

Embodied Rhetorical Genres

I’ve been the editor of American Randonneur, the official quarterly publication of Randonneurs USA, for four years, and in that time I’ve read hundreds of ride reports. Before that, it was reading ride reports that spiked my interest in randonneuring. Riding a lot, writing reports occasionally, and reading and editing others’ ride reports, I understand that writers shape and relive their experiences in their narratives. Shannon Walters sums up Aristotle’s notion that rhetoric belongs “to the genus of dynamis” with the claim that rhetoric, “like other arts, is produced by a transformative ‘coming into being” (32). Rhetoric is more skill than product, according to Walters, and in this case it is the skill to translate the “ thigh-thought, back-intelligence, calf-wit” mentioned by Fournel (128–29) into something intelligible. There are genre conventions that ride report writers abide by, probably mostly unconsciously, but somehow in rhythm with other ride report writers. My interest in and study of ride reports led to questions about arguments expressed by scholars of Rhetorical Genre Studies (RGS). Why do ride reports all seem to say the same thing? And what then to make of Catherine Schryer’s claim that genres are only “stabilized-for-now or stabilized-enough sites of social and ideological action” (204)? I’m citing Schryer’s often-used quote, but Carolyn Miller, Charles Bazerman, and many other noted RGS scholars argue that genres are rhetorical actions that respond to changing rhetorical situations and contexts, and as such, they constantly change. Schryer goes so far as to say that a “stable system,” including a stable genre, would have to be rhetorically unsound “because a stable system cannot respond to changes in audience or circumstance” (208). However, what I am suggesting in this essay is that if we allow that the body is a rhetorical agent, it may be possible that some embodied rhetorical situations present themselves again and again, because the answers are temporary or never entirely satisfactory.

Every time I try to put into words how and why the rhetoric of the ride report is deeply, materially, literally, embodied, I reach, almost as if into my body, for the right words. I am trying to pinpoint a practice, a form of moving-thinking-feeling-languaging that engages the whole body — body, mind, spirit — and is represented in the ride report as well as in related forms of writing about other kinds of life-intensifying challenges. Endurance runner Kilian Jornet writes, “I know that when I am running and skiing, my body and mind are in harmony and allow me to feel that I am free, can fly, and can express myself through all my talents. . . . Running provides my imagination with the means to express itself and delve into my inner self” (176). Jornet states that endurance running and the making sense of his experiences in language engage his whole being; he points to a form of life-affirming rhetoric that makes itself known in and through physical challenges as well as in his verbal explanations of those efforts. In an article from Le Petit Journal about the 1901 edition of PBP, Simon Levrai reports on Maurice Garin’s amazing ride: “1200 kilometers covered in 52 hours and 11 seconds, without stopping to sleep, almost without taking a breath, this is certainly one of the most magnificent tests of human endurance” (trans. mine). This brief news report celebrates the human potential that Garin’s effort exhibits, the willingness or desire of the human body to face and endure the “impossible.” The implicit awe and respect is directed not only toward Garin but toward humanity in general.

Embodied rhetoric can be a practice that allows people to creatively explore and better understand their rhetorical-biological selves, a point made by Jornet near the end of his book, “Perhaps I run because I need to feel creative. I need to know what is inside me and then see it realized somewhere outside me. . . . A race is like a work of art; it is a creation that requires not only technique and work but also inspiration to reach a satisfactory outcome” (177). Fournel, in the eloquent passage quoted earlier in this essay, and Jornet point to a biological-rhetorical impulse to engage in activities that demand a mind-body response to a bodily exigency. Both the physical effort and the thoughts and words formed around the effort are part of the creative act because we are a kind of being that makes sense of everything in language.

The existence of genres evidencing a deeply embodied rhetoric suggests that our bodies create and respond to rhetorical exigencies. Here I echo a conclusion drawn by LeMesurier: “The moving body as both responder and creator can be considered a material rhetorical device that . . . uses its own knowledge and forces, ever shifting in the albumen of bodily encounters, to yield rhetorical effects” (378). Rhetorical questions and exigencies exist in that “albumen,” a point suggested not only by the relative stability of the ride report across time and space, but also by the idea that the ride report responds to the same rhetorical questions as other quest stories including those I’ve cited as well as a host of others found in literary works, popular movies and religious stories. What is a person — mind and body together — capable of doing? What are our limits? Can we handle the exploration of those limits with grace and perhaps a little humor? What will we learn about ourselves and what it is to be human by testing ourselves? These questions haunt us, in part because they cannot be answered once and for all even for one person. And they continue to exist through time and across cultures. Bitzer argues that some well-established forms of discourse come to have a “power of [their] own,” so that the traditions endemic to these discourse forms “function as a constraint” upon any new possible responses (13). The ride report, a version of the quest or hero story, continues to exist and to draw creators and audience, in part because it has existed for so long and new writers and readers are steeped in its traditions. Additionally, however, it continues to exist because the exigency that inspires it continues to motivate people to bodily-rhetorical action.

Concluding Thoughts

I’ve noted my interest in ride reports and how they appear to defy basic precepts of Rhetorical Genre Studies. I’ve implied that Paris-Brest-Paris, Mecca for randonneurs, attracts because its history and everything about it is solidly grounded in the quest myth. That is, the ride report taps into a rhetorical situation that is “in some measure universal” and enduring (Bitzer 13). What my study offers, then, is not so much a counterpoint to the main ideas of Rhetorical Genre Studies but a reminder that the foundations of rhetoric are inexplicably and materially bound to our bodies. At the beginning of this essay, I said I wanted to take seriously the “embodied rhetoric of which we are constituted” (2), and this discussion has shown that the body can be a creative rhetorical agent, establishing and responding to rhetorical situations, sometimes with the cooperation of our minds, and sometimes in spite of what might seem like good sense. Like Condit, I believe we can see “an active biology in conversation with an active social coding system” (351). This study then suggests that the sources of and responses to rhetorical situations may take place at a fully embodied level, and this matters because it means that to be human is to be profoundly rhetorical.

As profoundly rhetorical beings, we create and use genres not only in response to situations encountered in our academic lives and in the business world, but just as importantly in situations where our bodies as well as our minds are equally and actively engaged. Or, this discussion also suggests our bodies are involved, to some degree, even in genres originating in professional contexts. That is, to explain and make use of a more fully embodied rhetoric, we must first accept that “embodied” literally means in the body. These conclusions raise questions for further studies of embodied rhetoric. The focus of this study, however, has been on the body as rhetorical actor, as thoroughgoing and intelligent rhetorician. What is to be learned from an endurance challenge, whether that challenge be a 750-mile bike ride, a fifty-mile run, or a three-month trek along a mountain trail? In each case, one is enticed by an activity that the mind and body together — working together — find engaging and meaningful, and we wonder how and why this is so. A bike ride might be so much more than just a bike ride. It may be a response to an embodied rhetorical situation the answer to which is ephemeral, individual yet universal, and reverently human.

Notes

1. “Randonneuring is long-distance unsupported endurance cycling. This style of riding is non-competitive in nature, and self-sufficiency is paramount. When riders participate in randonneuring events, they are part of a long tradition that goes back to the beginning of the sport of cycling in France and Italy. Friendly camaraderie, not competition, is the hallmark of randonneuring” (Randonneurs USA website).

2. PBP was a professional race until 1931, according to the Audax Club Parisien website.

Works Cited

Bazerman, Charles. Shaping Written Knowledge: The Genre and Activity of the Experimental Article in Science. U of Wisconsin P, 1988.

Bitzer, Lloyd F. “The Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy and Rhetoric, vol. 1, 1968, pp. 1–14.

Burke, Kenneth. Permanence and Change: An Anatomy of Purpose. 3rd edition. 1954. U of California P, 1984.

Chambard, Laurent. “Chasing The GRRizzlies (In The Heat!). . . . Gold Rush Randonnée, July 19–23, 2005.” 2005. TS. Personal Writing of Laurent Chambard.

Condit, Celeste. “The Materiality of Coding: Rhetoric, Genetics, and the Matter of Life.” Rhetorical Bodies, edited by Jack Selzer and Sharon Crowley, U of Wisconsin Press, 1999, pp. 326–56.

Crable, Bryan. “Symbolizing Motion: Burke’s Dialectic and Rhetoric of the Body.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 22, no. 2, 2003, pp. 121–37.

Dolmage, Jay. “’Breathe Upon Us an Even Flame’: Hephaestus, History, and the Body of Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 25, no. 2, 2006, pp. 119–40.

Fell, Harriet. “Paris-Brest-Paris 1975.” http://www.ccs.neu.edu. Accessed 20 Feb. 2016.

“Editorial.” Checkpoint, Dec. 1995, p. 3. Web. Accessed 21 Feb. 2016.

Fournel, Paul. Need for the Bike. Trans. Allan Stoekl. U of Nebraska P, 2003.

Greene, Nigel. “Living the Dream: One Account of Paris-Brest-Paris.” American Randonneur, vol. 18, no. 4, 2015, pp. 16–19.

Hawhee, Debra. “Bodily Pedagogies: Rhetoric, Athletics, and the Sophists’ Three Rs.” College English, vol. 65, no. 2, 2002, pp. 142–62

— . “Rhetorics, Bodies, and Everyday Life.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 36, 2006, pp. 155–64.

— . Moving Bodies: Kenneth Burke at The Edges of Language. U of South Carolina P, 2009.

Hayssen, Bob. “Paris Brest Paris 2015 in Under 84 Hours.” American Randonneur vol. 19, no. 1, 2016, pp.16–18.

Jornet, Kilian. Run Or Die. Velopress, 2013.

King, Trevor. “Paris-Brest-Paris: Thanks and Gratitude.” Checkpoint, 1999, p. 12.

Knoblauch, A. Abby. “Bodies of Knowledge: Definitions, Delineations, and Implications of Embodied Writing in the Academy.” Composition Studies, vol. 40, no. 2, 2012, pp. 50–65.

LeMesurier, Jennifer Lin. “Somatic Metaphors: Embodied Recognition of Rhetorical Opportunities.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 33, no. 4, 2014, pp. 362–80.

Levrai, Simon. “Le Semaine.” Weekly column. Le Petit Journal 1 Sept. 1901 (no. 563): np. randonneursbc.ca. 31 March, 2016.

Miller, Carolyn. “Genre As Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 70, 1984, pp. 151–67.

Mottiat, Louis. “Ma Victoire.” Le Miroir Des Sports 8 Septembre, 1921, p. 160. Randonneurs.bc.ca. Accessed 18 April, 2016.

Newman, Christine. “Red Hot Ride.” 2011 Yearbook: Paris-Brest-Paris. RUSA, 2012, pp. 21–23.

Rusch, Rebecca, with Selene Yeager. Rusch to Glory: Adventure, Risk and Triumph on The Path Less Traveled. Velopress, 2014.

Schryer, Catherine. “Records as Genre.” Written Communication, vol. 10, no. 2, 1993, pp. 200–34.

Selzer, Jack. “Habeas Corpus: An Introduction.” Rhetorical Bodies. Eds. Jack Selzer and Sharon Crowley. U. of Wisconsin Press, 1999, pp. 3–15.

Springsteen, Lois. “My Seventh PBP Adventure.” American Randonneur, vol. 18, no. 4, 2015, pp. 8–12.

Tyer, Vickie. “PBP 2015 Ride Report.” American Randonneur, vol. 18, no. 4, 2015, pp. 14–15.

Wadley, J. B. “Brestward Ho!” Chapter 2. Old Roads and New. J. B. Wadley, 1972. randonneurs.bc.ca. Accessed 14 April, 2016.

Walters, Shannon. Rhetorical Touch: Disability, Identification, Haptics. U of South Carolina P, 2014.

Wilcox, Hui Niu. “Embodied Ways of Knowing, Pedagogies, and Social Justice: Inclusive Science and Beyond.” NWSA Journal, vol. 21, no. 2, 2009, 104–20.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

- 20543 reads