The Hand of Racism: Using Dramatism to Discuss Racism Holistically

Michael Rangoonwala, California State University, Sacramento

Abstract

Divisive rhetoric abounds in the United States on the topic of racism. Finding productive and holistic ways of analyzing and discussing racism are vital. This essay proposes the use of the pentad method (act, scene, agent, agency, and purpose) and dramatic framing from Kenneth Burke’s theory of dramatism as useful toward that end. A case study of analyzing a racial narrative is performed on Nelson Mandela’s famous 1964 Rivonia Trial speech. In this paramount speech, Mandela advocates for a pragmatic transformation through agency and uses a comic frame to address the problem of racism in Apartheid. This essay concludes with a discussion of how the pentad and dramatic framing can be used to address racism by encouraging constructive dialogue and creative rhetorical approaches.

Introduction

The issue of racism and its effects, past and present, has nationwide attention in the United States. In the wake of racial violence in the news, the Black Lives Matter movement, and debates on critical race theory (CRT), the topic of racism has become highly controversial in politics, schools, homes, businesses, and religious institutions (Hamilton 66–70). Fueling this fire is the factual existence of racial disparities in the United States. A longitudinal study from 1950 to 2016 has found a persistent wealth disparity of median black households having less than 15% of median white households (Kuhn et al. 4). Numerous studies point to many other inequalities black Americans currently experience in health, access to healthcare, food insecurity, educational attainment, student loans, prison sentences, voting access, home ownership, and life expectancy (Hartman et al.). While the statistics of racial disparities is soberingly clear, the presumed causes and solutions are rigorously debated. Indeed, a 2020 Pew Research Center Survey found Republicans were twice as likely as Democrats to attribute economic inequalities to just life choices. Additionally, 50 percent of Democrats attributed racial discrimination as a cause of inequity, while only 11 percent of Republicans did (Horowitz et al. 31). With such differences, public rhetoric about racism tends to be polemic and dichotomous between party lines and ideologies (Hamilton 61). Clearly, there is an acute need for exploring productive – and not divisive - ways to analyze and discuss racism.

This essay contends that the methods afforded in Kenneth Burke’s theory of dramatism are effective at analyzing racial narratives from a holistic perspective, allowing for constructive dialogue and creative rhetorical approaches. The analysis explores Nelson Mandela’s famous 1964 Rivonia Trial speech, which he gave before being sentenced to life in prison for his efforts against Apartheid in South Africa. The results show how Mandela advocates for a pragmatic transformation through agency and uses a comic frame to address the problem of racism. Since racism is a universal issue, insights from analyzing Mandela’s discourse provides a comparison point to addressing racism in the United States. A discussion follows of how the pentad (act, scene, agent, agency, purpose) and dramatic framing can be used to encourage dialogue and creativity in addressing racism.

Race, Racism, and Rhetoric

Before explicating different views on racism, qualifying notes must be made on the definition of race and the scope of this essay. Conceptualizing “race” is a slippery and complex endeavor. In the United States, the term race has varied over time. Race used to refer to ethnic groups, such as the Irish or British races, but it later shifted to refer to biological differences based on color (Ratcliffe 14). This association was accompanied by oppressive economic and social hierarchies, with whiteness presumed at the top (Ratcliffe 14). Presently, the very nature of whether race is a legitimate category is still debated. A recent national survey of anthropologists’ view on race and genetics conclude, “Results demonstrate consensus that there are no human biological races and recognition that race exists as lived social experiences that can have important effects on health” (Wagner et al. 318). On the other hand, in a 2018 op-ed piece in the New York Times, David Reich, a Harvard geneticist, is wary of the orthodoxy of race as only a social construct. Reich argues that scientists and anthropologists should be open to the possibility of biological differences across racial populations, citing studies using modern genetic research. While important, this debate is outside the scope of this rhetorical study.

Rather, this essay is concerned with addressing racism or discrimination resulting from racial prejudice. Regardless of one’s view on the legitimacy and definition of race, the negative social consequences of racial discrimination are undeniable. As such, one can examine race as a trope, as “It signifies socially constructed ‘common-sense’ attitudes and actions associated with different races” (Ratcliffe 12). Ratcliffe outlines four major cultural logics which views the trope of race in different ways, namely the logic of white supremacy, color-blindness, multiculturalism, and CRT (14). A white supremacy logic views race as a hierarchy based on biological differences. A color-blindness logic eliminates the concept of race both culturally and biologically. A multicultural logic values the use of ethnicity, or cultural heritage, over race. Finally, a CRT perspective posits race as a social construct and mandates the study of race to bring about social justice (Ratcliffe 14-15).

CRT merits further explanation due to its prevalence in the literature and public forum. CRT finds it roots in critical legal studies in the 1970’s which questioned the fairness and neutrality of the law (Brayboy 428). Since racial disparities continue to exist decades after civil rights legislation, CRT seeks to understand how racism continues to operate. First, CRT claims the concept of race is a social construction to benefit the dominant race. Thus, in the United States, being white is seen as normalized, privileged, and deeply institutionalized. Racism is seen as endemic in all parts of society, particularly against people of color. To address this, political reform, educational efforts, and social justice are pursued (Bernal 110-111; Hamilton 87-88). CRT rejects the ideas of meritocracy, color-blindness, equal opportunity, and liberalism (Brayboy 428; “Critical Race Theory” 6). Another main principle is the validation of experiential knowledge from people of color (Brayboy 428; Solórzano and Yosso 26). Known as counter-stories, the perspectives of oppressed groups can offer a different view compared to the master narrative of the dominant culture (Solórzano and Yosso 27-33). Finally, the scope of CRT is expansive because racism is believed to overlap with other subordinated identities - a concept called intersectionality (“Critical Race Theory” 10).

CRT has not gone unchallenged. Christopher Rufo, a senior fellow from the conservative thinktank the Manhattan Institute, has led the charge in strongly opposing the fundamental tenets of CRT (Hamilton 72). Rufo states, “In simple terms, critical race theory reformulates the old Marxist dichotomy of oppressor and oppressed, replacing the class categories of bourgeoisie and proletariat with the identity categories of White and Black.” While Rufo agrees with the premise that residual effects of racism is a problem in America, he strongly rejects the solution CRT proposes of “moral, economic, and political revolution.” CRT is accused of encouraging race essentialism, active discrimination and reverse racism, restricting free speech, manipulation, neo-segregation, and anti-capitalism (Rufo). The conservative position supports the ideal of equality and critiques CRT’s notion of equity, claiming it divides people into racial groups resulting in racial discrimination (Rufo). On his website, Rufo provides phrases for “winning the language war” and tips for “using stories to build the argument.” Clearly, views on racism are divided and a focus on rhetoric is front and center.

Between this spectrum of opinions, there are those who share the social justice values of CRT but disagree on its assumptions, strategies, and conclusions. For example, Reilly compares and contrasts the catholic social teaching of the preferential option for the poor with CRT. Some common ground is found in recognizing underprivileged groups, redistributing resources, and abolishing oppressive structures (Reilly 655-656). However, CRT’s end goal of group-based liberation is deemed problematic because it results in fracturing society. Instead, “The end that we should be striving for, however, is solidarity: organic, permanent, and loving” (Reilly, 659). In a similar manner, the protestant Christian scholar John Piper supports the generic goals of CRT such as working against systemic racism and individual prejudice, but warns that “minimizing other relational dynamics (like love and humility and graciousness), can skew our understanding and yield unhelpful strategies.” Additionally, CRTs assumptions of self-identity construction and subjective truth are untenable with these faith worldviews (Piper; Reilly 657).

In summary, when it comes to race, racism, and rhetoric in the United States, discourse is contentious. The debate goes beyond the causes and solutions of racism to the labels used to define other viewpoints. For instance, what critical race theorists call “social justice,” Rufo terms as “Marxism.” What critical studies harks as “social constructs,” a classical liberal perspective champions as “social contracts” (Halsey). Arguments can spiral into circular accusations of racism and reverse-racism. Another conversational hurdle is with clarity. CRT has been critiqued of using vague jargon and dismissing opposition as proof of racism and white denial (Rufo; Halsey). With such a spectrum of viewpoints, one-sided claims to truth, and challenges with clarity, how can productive dialogue occur? How might different perspectives unify to counter the problem of racism together? To these ends, this essay proposes using the methods of the pentad and dramatic framing from dramatism. Rather than taking a position on the debate, dramatism is neutrally presented as a method capable of integrating diverse viewpoints.

Dramatism as a Method of Rhetorical Analysis

During World War II, Kenneth Burke, an American literary critic, noticed the dangers of both absolutist, fascist rhetoric and uncritical unity in countering it (Weiser, 291). He responded by developing an alternative approach through the theory of dramatism, which “encourages a poetic dialectic - the celebration of differing perspectives - and transcendence - the search for points of merger - in an effective parliamentary debate” (Weiser 287). Burke encourages productive debate by first focusing on human motivation and symbolic action found in language (Foss et al. 195). To Burke, language is not just a reflection of the world but is itself a form of action. Burke distinguishes the word “action” from “motion,” which is merely a blind, unmodified force (Foss et al. 195). Burke describes the human as “the symbol-using (symbol-making, symbol-misusing) animal” (Language as Symbolic Action 16).As Burke’s theory has a large scope, this essay focuses on using the pentadic and dramatic framing methods, as they are pertinent to Mandela’s speech, and by extension, discussions on racism in the United States.

The Pentad

The pentad is Burke’s systematic method to examine a symbolic drama from multiple perspectives (Crusius 27). It consists of five grammatical terms, rather than questions or answers, to invite dialectic criticism (Weiser 294). These terms are act, scene, agent, agency, and purpose. All the terms are connected to each other and are not mutually exclusive (Burke, A Grammar of Motives 127). Burke gives the metaphor of the five fingers on a hand to describe the unity of the five terms (Anderson par. 1). Crusius explains, “For drama implies action and action implies, among other terms, an act itself, someone to do the act (agent), a place and a time for the act (scene), an end of or intent for the act (purpose), and a means for doing the act (agency)” (27). Additionally, if one term is emphasized above the others, it becomes the lens through which all the other terms are viewed. Hence, Burke describes a school of philosophy for each term (A Grammar of Motives 127). In summary, the pentad is useful in understanding both how a rhetor names the situation and his/her accompanying worldview. The following paragraphs will define the pentadic terms, identify their idiosyncratic philosophies, and explain how to apply the pentad.

Act is defined as any purposive action (Foss et al. 199). In other words, it answers what happened. Burke claims that act is the central, beginning term that develops the pentad since it creates a situation to examine in the first place (Brock 100). Its corresponding philosophic terminology is realism (Burke, A Grammar of Motives 128). Realism, in contrast to nominalism, can be defined as “the doctrine that universal principles are more real than objects as they are physically sensed” (Foss 389). With realism then, language is utilized to understand objective reality and universal truths. However, while Burke identifies realism as the philosophical school for act, he further describes action in ways connotating freedom, choice, and essence. For instance, he states that the “act itself alters the conditions of action” (A Grammar of Motives 67), implying an existentialist philosophy in which actions form essence.

Scene answers the question of when and where the action occurred. In addition to physical environments, scene can represent ideas such as cultural movements or communism. The scope of the context assigned to the scene, such as the difference between a city and a continent, is termed the circumference of the analysis (Foss et al. 199; Rutten et al. 637). Lastly scene has the philosophic terminology of materialism (Burke, A Grammar of Motives 128). Materialism as a system “regards all facts and reality as explainable in terms of matter and motion or physical laws” (Foss 389). Fay and Kuypers describe it another way as determinism (202).

Agent, or who is performing the act, has the philosophic terminology of idealism (Burke, A Grammar of Motives 128). Idealism is “the system that views the mind or spirit as each person experiences it as fundamentally real, with the universe seen as mind or spirit in its essence” (Foss 389). With this philosophy, a human’s mental capacities form reality. Fay and Kuypers also associate idealism with self-determination (202). In idealistic discourse, agents appear rational and empowered (Tonn et al. 254), using “an individual’s inner resources to overcome adverse circumstances” (Fay and Kuypers 202).

The term agency refers to how an act occurs, and its matching philosophic terminology is pragmatism (Burke, A Grammar of Motives 128). In pragmatism, “the meaning of a proposition or course of action lies in its observable consequences, and the sum of these consequences constitutes its meaning” (Foss 389). In other words, the means to an end is featured and goodness or truth is indicated by the outcomes. Burke describes the school of pragmatism in an example with science, “Once Agency has been brought to the fore, the other terms readily accommodate themselves to its rule. Scenic materials become means which the organism employs in the process of growth and adaptation” (Burke, A Grammar of Motives 287). This example illustrates how a focus on agency causes a focus on processes.

The fifth term, purpose, describes the agent’s reason for doing the action (Foss et al. 199). Foss et al. clarify that purpose should not be confused with motive, which is only discovered using all five terms (200). Purpose has the philosophic terminology of mysticism in which “the element of unity is emphasized to the point that individuality disappears. Identification often becomes so strong that the individual is unified with some cosmic or universal purpose” (Foss 389). The accentuation of purpose emphasizes the ends, rather than the means, as the focus of discourse (Fay and Kuypers 202). Finally, Burke added a sixth term later in his work titled attitude, but it will not be elaborated in this essay.

To apply the pentad to a rhetorical artifact, the first step is to name or define each of the terms. The next step examines the ratios, or relationships, between the terms. Twenty possible ratios can be created with the terms. The ratio is thought of as potential to actual; the first term creates possibilities for the second term to actualize (Tilli 45). For instance, a teacher teaching would be a predictable agent-act relationship (C. Rountree and J. Rountree 354). Pentadic pairs do not need to stay consistent with their pentadic expectations however. A term can act unpredictably to upset the ratio and transform or reverse the relationship (Tilli 45).

After systematically pairing and evaluating the second term in light of the first, a pattern of dominant terms should emerge (Rutten et al. 636). The central, dominating term will define the other pentadic terms and represent a worldview or orientation (Foss et al. 201). Burke explains that analyses of the ratios are “not terms that avoid ambiguity, but terms that clearly reveal the strategic spots at which ambiguities necessarily arise” (A Grammar of Motives xviii). Developing the critical skill of noting ambiguities is central to interpreting the pentad and thus the motive. Additionally, a pentadic analysis is not limited to just within an artifact, but it can also examine the artifact itself as the act in a larger context (Foss et al. 201).

Using the pentad method is useful for analyzing a rhetor’s motives, understanding their orientation and interpretations, and identifying alternative perspectives (Foss et al. 201). Burke created dramatism to inspire a dialectic view of rhetoric (Weiser 294). The pentad is a method in which to discover the motive and philosophy of a symbolic act.

Dramatic Framing

Dramatic framing is another significant form of analysis from Burke. Burke identifies the impact of literary art forms and how it frames the attitudes of an event. They act as what he terms “equipment for living,” which enable people to deal with the complexity of an event and establish an orientation (Ott and Aoki 281; Rutten et al. 634). According to Burke, symbolic forms can be organized into frames of rejection or acceptance (Ott and Oaki 281). The frame of rejection takes the “literary forms of elegy, satire, burlesque, and grotesque,” but “By ‘coming’ to terms’ with an event primarily by saying ‘no,’ frames of rejection are unable to equip individuals and groups to take programmatic action” (Ott and Oaki 281). Alternatively, frames of acceptance focus on obtaining resolution and are often enacted in the literary forms of epic, tragedy, and comedy. For instance, using a scapegoat mechanism to reveal guilt and call for redemption is termed a tragic acceptance of the situation. The problem with this frame, though, is that it does not encourage ethical learning (Ott and Oaki 281) and can be described as fatalistic (Smith and Hollihan 589). Burke further clarified two forms of tragic framing in a footnote in Attitudes Toward History (188-189). A factional tragedy, typically seen in war rhetoric, externalizes all guilt by attributing evil to another party. In contrast, in a universal tragedy, guilt is internalized and shared by everyone, as the audience is invited to identify with the protagonist. A universal tragedy is similar to comic framing in creating a sense of “humble irony” and “the role of double vision” (Desilet and Appel 349). The difference is that a tragedy names one a villain, while a comedy labels one a fool: “Like tragedy, comedy warns against the dangers of pride, but its emphasis shifts from crime to stupidity” (Burke, Attitudes Toward History 41).

Burke encourages people to use a comic frame to achieve lasting peace. A comic frame, not to be confused with comedy as hilarity, encourages self-reflection and the advancement of social knowledge to avoid future mistakes (Ott and Oaki 280-281). It stands in opposition to victimage by encouraging redemption for the perpetrator and focusing on the causal conditions of the grievance (Smith and Hollihan 589). For example, Gandhi’s movement of civil disobedience in India illustrates the comic frame, as his focus was on “evil deeds” and not the “evil doer” (Carlson 450).

Another important, related concept to dramatic framing is terministic screens. Burke defines terministic screens saying, “Even if a given terminology is a reflection of reality, by its very nature as a terminology it must be a selection of reality; and to this extent it must function also as a deflection of reality” (Language as Symbolic Action 45). In other words, the terms and vocabulary one uses is the lens or ideological system through which they view reality. For example, if medical terminology is used to describe a disabled person, the lens the individual is viewed is through a pathological understanding (Rutten et al. 635). Foss et al. note that a person’s terminology is often related to their occupation or career (206). In sum, noting terministic screens reveals the rhetor’s dramatic framing of reality and biases.

Defining Racial Narratives

Since this essay examines a racial narrative, it is necessary to provide a brief definition and overview. The use of the term racial narrative simply means a narrative, story, or testimony that features discourse centered on race. The speech Nelson Mandela gives at the Rivonia Trial can be considered a racial narrative and may have transferable insights into racism in general. In this trial, Mandela gives a testimony of his own life, of the actions of the African National Congress (ANC), and the experiences of Africans. Thus, it is both an autobiography and biography. Mandela’s speech arguably fits the category of a counter-story showing the perspective of black Africans in South Africa.

The pentad is both suitable and effective for studying narratives. In the last 45 years, the study of narratives has flourished in multiple disciplines such as history, ethnography, psychology, communication, and more. Additionally, “Whereas the focus used to be primarily and exclusively on the form and content of stories, there is now an increasing attention for the political, ideological, cognitive, and social function of narratives” (Rutten and Soetaert 328). Scholars have applied the pentad to a variety of narratives ranging from personal experiences to fictional stories (Rutten and Soetaert 337). Bruner, an educational psychologist, claims that “narrative imitates life, life imitates narrative” (692), and applies the pentad to narratives to discover where the tensions are in the story (Bruner 697; Rutten and Soetaert 330-331). In a similar spirit, this study applies the pentad specifically to a racial narrative.

Nelson Mandela’s 1964 Rivonia Trial Speech

Nelson Mandela has placed his stamp upon history and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 for his efforts in eradicating the Apartheid system in South Africa (“Nelson Mandela”). Apartheid was a violent period in history from around 1950 to 1994 in which the white minority in South Africa created legislation to racially segregate South Africans in all aspects of society (“Apartheid”). For instance, through the Land Acts, 80 percent of the land became owned by the white minority and was used exclusively for their residential or business practices. Additionally, pass laws required non-white people to carry documentation to travel. Eventually, international pressure and internal reform brought about national elections in 1994 in which Nelson Mandela became the first black president (“Apartheid”).

The artifact under consideration in this analysis is the last 10 minutes of Nelson Mandela’s pivotal Rivonia Trial Speech in June 1964. Before the trial, Mandela was a nonviolent activist with the ANC, a black liberation group. However, since the government increased its violence, and non-violent protests gained little, Mandela and other activists responded with sabotage (“Nelson Mandela”). Alongside nine other accused ANC leaders, the presence of international jurists, and a biased court system, Mandela defended himself against charges of treason and supporting communism (Nicholson 123-125). In the end, he barely avoided a death sentence and was sentenced to life in prison until he was released in 1990 (Nicholson 126). As for his four-hour speech, it was later published and achieved global fame in its eloquent resistance against Apartheid (“Listen: Two Mandela Speeches”; “Nelson Mandela”; Nicholson 125).

An important consideration is that this dramatistic analysis will focus on the last 10 minutes of the speech, which contain Mandela’s most emotional and epic conclusions (see “Listen: Two Mandela Speeches” for audio, transcription, and all quotations from Mandela’s speech). Additionally, it is a manageable selection from his four-hour speech to analyze. Another important consideration is that the pentadic analysis will be done in isolation, or within the speech. The alternative way of utilizing the pentad is to examine the artifact itself as the act in a larger context (Foss et al. 201), but this is not the case for this analysis.

Transforming the Hand of Racism

The first way to uncover the implicit messages inside a racial narrative through the pentad is to identify the pentadic terms. Indeed, identifying the pentadic terms reveal Mandela’s rhetorically nuanced casting of the situation. Following this, the pentadic ratios are analyzed to illuminate his philosophic worldview.

Nelson Mandela’s Counter-Story

First, naming the terms shows that Mandela creates a juxtaposition of an oppressive present and a hopeful future. For his present situation in South Africa, Mandela describes a scene of political racialism through white supremacy. He says, “The lack of human dignity experienced by Africans is the direct result of the policy of white supremacy.” He later states that the “ANC has spent half a century fighting against racialism.” Mandela is critiquing the one-sided political monopoly of the white minority. The white minority are implied as the agents in this drama. Mandela implies their purpose as preserving white supremacy when he calls for equal voting: “I know this sounds revolutionary to the whites in this country, because the majority of voters will be Africans. This makes the white man fear democracy.” The fear of losing control motivates the ruling white minority to preserve their situation. In order to do this, they enact an agency of racist legislation. Mandela goes into detail describing “legislation designed to preserve white supremacy.” For example, Mandela critiques menial work assigned to Africans, pass laws, and the absence of equal political rights. Finally, Mandela depicts the consequence of racist legislation, or act, as the lack of human dignity for Africans. Mandela attributes poverty, the breakdown of family life, “a breakdown in moral standards, to an alarming rise in illegitimacy, and to growing violence which erupts not only politically, but everywhere” as ultimately stemming from racist legislation such as pass laws. In summary, there is pentadic coherence to explain the situation Mandela describes of an oppressive present as follows: for the purpose of preserving white supremacy,white minority agents create an act of abusing the human dignity of Africans through the agency of racist legislation in a scene of political racialism.

Mandela then strategically juxtaposes the oppressive present with a hopeful future, creating two sets of pentads. The second pentad contains terms that are exactly opposite of the oppressive present pentad. This nuanced casting of two situations illustrates Mandela advocating for a complete transformation of terms. Mandela states, “I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities.” This quote succinctly demonstrates Mandela describing a scene of democracy and equality, for the purpose of racial harmony and freedom for all. To accomplish this, Mandela proposes a new agency: “Above all, My Lord [the judge], we want equal political rights, because without them our disabilities will be permanent.” Mandela says voting is “the only solution which will guarantee racial harmony and freedom for all.” Having equal political rights through voting is accomplished by the agents of all people regardless of color or race. Consequently, the new agency of voting will produce an act of the restoration of human dignity. As Mandela states, “The only cure is to alter the conditions under which Africans are forced to live and to meet their legitimate grievances.” He then elaborates on all the “wants” that Africans are denied of. These wants, such as good pay or the ability to work or travel anywhere, are in direct contrast to the oppressive conditions Mandela describes under racist legislation. In overview, Mandela paints a hopeful scene of democracy and racial equality for the purpose of racial harmony and freedom for all, in which all people as agents can perform the agency of voting to create an act of restoring human dignity.

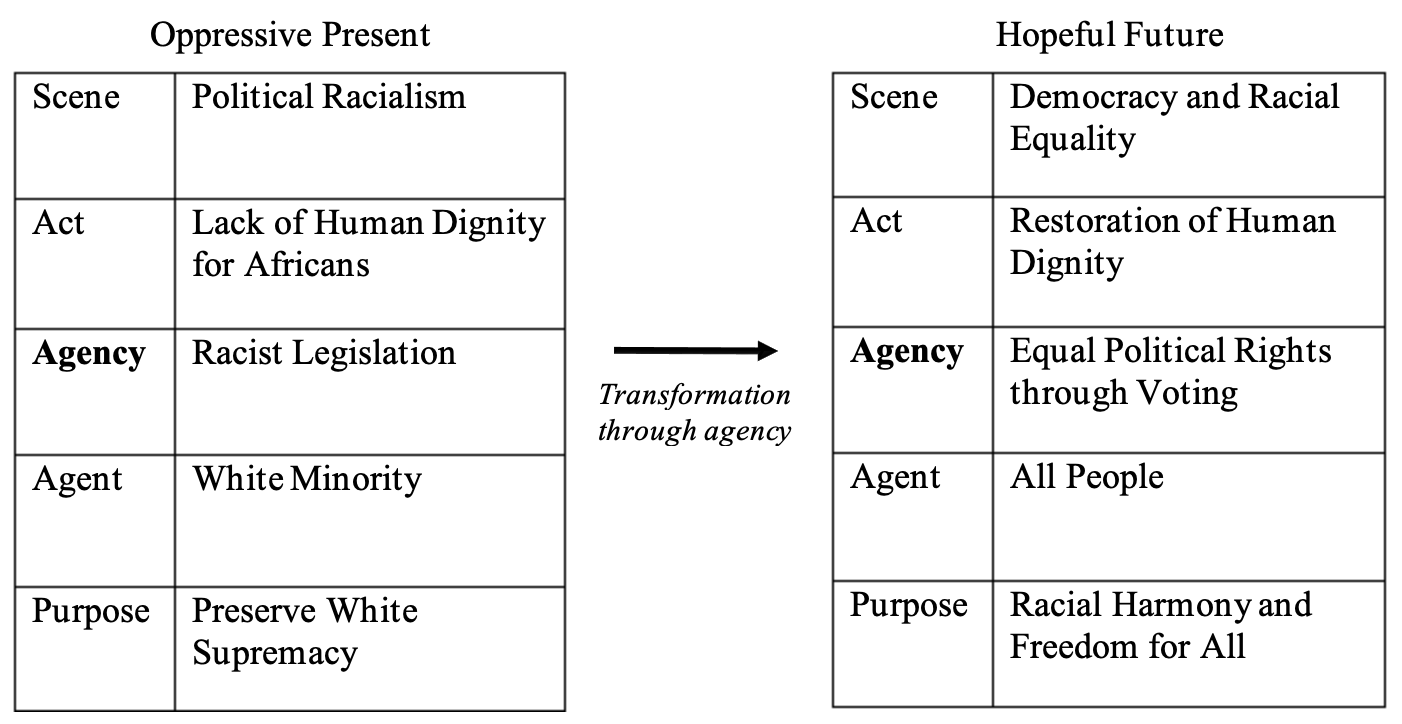

In summary, the juxtaposition of an oppressive present and a hopeful future is illustrated through the first step of naming the pentad. The implicit, rhetorical message revealed is Mandela’s exhortation for complete transformation. See Figure 1 below for a visual of the pentadic analysis.

Figure 1.

Second, the arrangement of pentadic terms illuminate Mandela strategically crafting a counter-story. A counter-story presents the perspectives of the oppressed to “shatter complacency, challenge the dominant discourse on race, and further the struggle for racial reform” (Solórzano and Yosso 32). It is significant how Mandela arranges the pentadic terms because it shows his perspective. For instance, an alternative view—and perhaps the white minority’s view—could feature the violent situation, poverty, and breakdown of moral standards in South Africa as the scene. With this point of view, a variety of interpretations of the causes of the scene could be made, such as placing the locus of blame on the black South Africans. Instead, Mandela posits the turmoil in the country as an act. Naming the problems as an act removes the conversation from abstraction and makes it personal, indicating an intentional agent, agency, scene, and purpose at work. Mandela provides a line of logic that unjust pass laws ultimately cause poverty and violence. Overall, Mandela is explaining a counter-story on behalf of the oppressed African people that racist legislation is the root cause of the societal problems. Through examining the arrangement of pentadic terms, a window is created to peer inside the racial narrative.

Rights Realize Reality – A Pragmatic Worldview

The second step of the pentad method is to analyze the pentadic ratios or relationships. Analysis of the ratios shows a rhetor’s implicit, key motives. First, it is demonstrated that Mandela features agency as the dominant term through a process of elimination. Next, it is explored how agency as the dominant term reveals Mandela’s philosophic worldview.

At first it appears scene would be the dominant term in Mandela’s speech. Indeed, scene fits logically in controlling the other terms. The scene of political racialism could be seen to control or cause the act (lack of human dignity for Africans), agency (racist legislation), or purpose (to preserve white supremacy). However, Mandela presents the scene in subordination of agency when he states, “The lack of human dignity experienced by Africans is the direct result of the policy [emphasis added] of white supremacy.” The policy is the root cause while white supremacy is a descriptor. Granted, it may be unclear which preposition, “of the policy” or “of white supremacy,” is more significant in this sentence. The rest of the speech confirms a focus on agency, though, as Mandela centralizes issues in legislation, pass laws, and voting.

One could also argue that purpose is the dominant term in this speech. The purpose of preserving white supremacy could logically enact an agency of racist legislation, a scene of political racialism, or an act of abusing the human dignity of black Africans. Yet similar to scene, Mandela subordinates the purpose term when he says, “Legislation [emphasis added] designed to preserve white supremacy entrenches this notion.” Once again, Mandela highlights legislation. Furthermore, the rhetoric employed by Mandela in this speech is not characteristic of dramatistic purposive rhetoric. For example, in Fay and Kuyper’s analysis of John F. Kennedy’s (JFK) Berlin speeches, they claim JFK emphasizes purpose by using a prophetic and moralistic tone and employing the unconditioned future tense (207). Mandela does not employ similar wording as he passively uses the present perfect tense in the last paragraph of his speech saying, “I have dedicated my life to this struggle,” “I have fought,” or “I have cherished the ideal.” Mandela’s tone is more so somber than prophetic, offering a description of the oppressive present and hoping for change. This is not surprising considering his context—a prisoner on trial defending against the death penalty.

The term act, or the lack of human dignity for black Africans, does not logically realize the potential in the other terms in this case. Instead, it is often explained as a result of the agency of racist legislation. Similarly, the term agent, or the white minority, could not control the other terms except for maybe the purpose of preserving white supremacy. Also, Mandela only mentions “the white man” twice and focuses his discourse more so on agency, act, and scene.

After examining the relationships in all the ratios and “the strategic spots at which ambiguities necessarily arise” (Burke, A Grammar of Motives xviii), it becomes convincing that agency is the dominant term in this artifact. Previous examples have illustrated how Mandela desires transformation through agency by emphasizing key terms such “legislation,” “policy,” “pass laws,” and “equal political rights.” Additionally, Mandela’s counter-story positions unjust legislation as the ultimate cause of poverty and violence in the country. Since Mandela’s discourse mainly addresses aspects of agency, act, and scene, the main ratio pairs are Agency:Act and Agency:Scene. It can be concluded that Mandela’s main exhortation is to transform an oppressive present to a hopeful future by changing the nature of legislation or agency (refer to Figure 1). “Above all,” Mandela states, “we want equal political rights.” To transform a situation, a pentadic term can act unpredictably to upset the ratio and transform or reverse the relationship (Tilli 45). In this case, the pentadic term of agency is not being used to reverse a single pentadic ratio; rather, it is acting as a pivot to transform into a whole new pentad. Through changing agency, all the other terms will be changed as well. This is evidenced in that agency remains the dominant term in both pentads. It is the definitions of the terms that are changing. Using the pentad is monumental in understanding the course of action Mandela recommends and thus his key message.

Lastly, the dominant term reflects the rhetor’s motive or worldview through a corresponding philosophic terminology (Foss 389). Since agency is featured in this speech, Mandela is implying a pragmatic worldview to change the circumstances of Apartheid. Mandela’s discourse focuses on processes or means, which is caricature of a pragmatic philosophy. For example, Mandela calls for a democratic voting process, the elimination of pass laws, and less governmental regulation of daily life for Africans. Mandela’s argument is that by examining the consequences of legislation, one can determine the political direction South Africa should take. In making the case for the direction of democracy, Mandela first presents the dire consequences of the present racist legislation: poverty, violence, and inhumane treatment of black Africans. Afterwards, Mandela describes the positive consequences of having just and democratic legislation: human dignity and equality. Clearly, Mandela is exhibiting a pragmatic worldview in which truth or goodness is to be assessed by the consequences of processes.

Furthermore, one can elaborate on the main ratios, Agency:Act and Agency:Scene, in relation to their philosophic worldviews. The Agency:Act ratio translates into pragmatism defining realism or existentialism. In terms of Mandela’s speech, the message is that enabling just processes of legislation will create a reality or essence that is just. More specifically, equal democratic elections will inspire acts that restore and maintain human dignity for all. Equally so, unjust processes lead to oppressive acts. The Agency:Scene ratio translates into pragmatism shaping materialism. In the case of Mandela’s speech where scene represents an idea (political racialism or democracy), the implicit message is that legislation will ultimately shape the political landscape of the country. Just legislation will realize true democracy, not the other way around. Likewise, unjust legislation will realize a racist climate. Overall, Mandela is exhorting to change the unjust scene and dire acts of the oppressive present through first changing the dominant term of agency, and hence implies the philosophical worldview of pragmatism. Through dramatism, these implicit messages have been explored inside the racial narrative.

The Comic Foolishness of Racism

By examining Mandela’s discourse through a dramatic framing lens, it can also be argued Mandela uses a comic frame. Throughout the speech, his tone and words are educational and not derisive. As Carlson notes in his essay on Gandhi’s movement, “The comic frame identifies social ills as arising from human error, not evil, and thus reasons to correct them” (Carlson 448). In a similar manner, Mandela’s discourse focuses on reasoning instead of accusation. While very similar to the tragic universal frame, the comic frame may be more suitable to describe Mandela’s approach because of his focus on foolish human error versus shared guilt. Mandela’s comic spirit is shown through how he addresses a terministic screen to build universal identification, emphasizes impartiality, and focuses on agency to solve societal problems.

First, Mandela establishes universal commonalities by exposing and critiquing the terministic screen of white supremacy. In the first paragraph of the speech, he states, “White supremacy implies black inferiority.” Mandela then describes the consequences of viewing blacks as inferior such as expecting them to do only menial tasks. “Because of this sort of attitude, whites tend to regard Africans as a separate breed. They do not look upon them as people with families of their own; they do not realise that we have emotions—that we fall in love like white people do.” Mandela cites more examples and ends with “And what ‘house-boy’ or ‘garden-boy’ or labourer can ever hope to do this?” In this last sentence, Mandela is pointing out how labeling Africans with economic-like terminology selects a reality that Africans are inferior and deflects their hope to live with dignity. In other words, Mandela is exposing a terministic screen. By appealing to the universal human traits of love and family, Mandela builds identification with his wider audience.

The comic approach is also apparent when Mandela appeals to impartiality in the last two paragraphs of his speech. Mandela states, “Political division, based on colour, is entirely artificial and, when it disappears, so will the domination of one colour group by another.” He elaborates that the goal of the ANC is “fighting against racialism. When it triumphs as it certainly must, it will not change that policy…I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination.” These excerpts show Mandela is more concerned with eliminating racism than with casting blame or guilt to a perpetrator. Mandela said he desires a “free society in which all persons [emphasis added] will live together in harmony.” It is clear Mandela is not using a rejection frame, for he suggests programmatic action for a democracy. Mandela is emphasizing a comic frame to advance social knowledge and avoid future mistakes.

Furthermore, Mandela’s focus on agency complements a comic approach. Instead of labeling the white South Africans as inherently evil, vicious, or criminal, he focuses on the foolishness of the policy of white supremacy and its negative societal effects. Through crafting a counter-story, Mandela provides a line of logic that unjust, racist pass laws ultimately cause poverty and violence, which affect both blacks and whites as “violence is carried out of the townships into the white living areas.” Arguably, keeping the focus on legislation and the problem of racism averts the speech from slipping into a factional tragic frame of blaming. Indeed, Mandela rarely mentions the agent of white men in the speech artifact, which may indicate he is trying to focus on the causal problems and long-term solutions.

In summary, Mandela’s attempts to reason through building identification, emphasizing impartiality, and focusing on agency exemplify the comic frame to bring about an ideal society. These rhetorical moves may serve to create what Burke termed “maximum consciousness” or self-reflection (Attitudes Toward History 171). Ironically, Mandela is seriously comic, and concludes his speech with his famous words, “it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Discussing the Hand of Racism

Amid the spectrum of contentious rhetoric on racism in the United States, there is an acute need for finding productive ways to discuss racism. The case study of Mandela’s speech demonstrates how the methods in dramatism may be helpful toward this goal. Specifically, pentadic and dramatic framing analyses allow for constructive dialogue and creative rhetorical approaches for addressing racism.

Promoting Constructive Dialogue through Clarity

For constructive dialogue to occur, a necessary precursor is clarity. Clarity is especially important in discussions of racism, where definitions and assumptions can be vague and abstract. In the present analysis, the methods in dramatism create clarity by illuminating the rhetor’s perspective, underlying philosophy, and holistic message.

First, dramatism helps one accurately understand a rhetor’s perspective. The analysis details how Mandela crafts a counter-story to explain the abuse of black Africans as an act, indicating an intentional agent, agency, scene, and purpose at work. Furthermore, the juxtaposing pentads of an oppressive present and a hopeful future reveal what Mandela believes are the causes and solutions of racial discrimination. He also critiques the terministic screen of labeling Africans with economic-like terminology, which fails to capture the universal human traits of love and family. Finally, understanding that Mandela uses a comic frame for his arguments helps to comprehend his goals for universal peace and long-term solutions. Overall, the terminology from dramatism provides clarity on Mandela’s perspective.

Second, dramatism provides the tools to identify a rhetor’s underlying philosophy. Changing agency through the right to vote is highlighted as Mandela’s central appeal, indicating the philosophy of pragmatism. Through analyzing the pentadic ratios, Agency:Act and Agency:Scene are found to be the key pairs. In other words, Mandela assumes that changing the processes of legislation will create a just reality and democratic climate. Identifying one’s assumptions is a vital step to bringing clarity to a discussion, regardless if the other agrees.

Third, clarity is a natural consequence of the pentad because identifying all five grammatical terms results in a holistic message. As Crusius notes, “The Pentad's main purpose is to overcome the limitations of any single critical vocabulary” (27). Whether one is analyzing a racist event or racial narrative, the perceived act, scene, agent, agency, and purpose must all be labeled. Additionally, the effort of organizing the relationships between the terms may reveal incompatibilities. If found, fixing logical errors creates more cohere arguments.

Arguably, one of the main issues with current discourses about racism is when only a single pentadic term is highlighted. For example, CRT seems to posit racism in mainly scenic language when they describe racism as “endemic, permanent” (Solórzano and Yosso 25), at the institutional, cultural, and individual level (Museus and Park 552), as the “center of analysis” (Love 228), where it “permeates society” (Hamilton 88), and is central to other forms of subordination (Bernal 110). Emphasizing scene follows the philosophy of determinism, where free will is inconsequential (Fay and Kuypers 202). At the other extreme, a classical liberal perspective emphasizes the agent and the philosophy of self-determination, believing in meritocracy, equality, and the ability of “an individual’s inner resources to overcome adverse circumstances” (Fay and Kuypers 202). Clearly, scene and agent have contrasting philosophies (Crusius 27). This is also apparent across political lines. Republicans are twice as likely as Democrats to attribute economic inequalities to life choices, whereas Democrats are more likely to point to structural barriers like racial discrimination (Horowitz et al. 30). To combat vagueness and one-sided claims to truth, perhaps what is needed is for all parties to present holistic messages, where all five grammatical terms and their relationships are expressed. After all, the pentad represents a hand and not just a finger. But what if both sides provide holistic messages and they are still at odds with each other? At the least, laying out viewpoints through the pentad provides clarity to aid discussions. Better yet, maybe a humble admission can be made that one school of philosophy cannot accurately portray reality. Like a diamond with many facets, being open to other perspectives can provide a more encompassing view of the world.

Promoting Creative Rhetorical Approaches

In addition to clarity, the methods in dramatism allow for creativity in addressing racism. The pentad can ironically provide a serious conversation by being playful with the terms. For instance, which pentadic term(s) should be the focus of a rhetor to effectively combat racism? One can extrapolate the answer using singular, scaffolded, or simultaneous pentadic approaches. Additionally, dramatic frames can be combined to create new rhetorical strategies.

A singular pentadic approach analyzes how transformation occurs from one pentadic term changing. Most pentadic analyses feature one pentad and explicate the ratios within the singular pentad (e.g., Fay and Kuypers; Rutten et al.; Tonn et al.). Sometimes a term can act unpredictably to upset the main ratio and reverse the relationship (Tilli 45). Yet in Mandela’s speech, the central term of agency acts like a pivot between two pentads. If agency is redefined, then one pentad swings into becoming another pentad. From Mandela’s perspective, changing the agency of racist legislation is the key to end domination.

But was Mandela’s approach successful in South Africa? Mandela’s hopeful belief could be explained by the context of his speech. At the time, he was still in a pre-civil-rights context in South Africa. Democratic elections were only held thirty years later in 1994 (Nicholson 126). Amid oppression, Mandela was searching for practical steps to achieve the ideal of harmony. Although South Africa is now a democracy, South Africa still struggles with the “entrenched social and economic effects” of racism (“Apartheid”). Proof of this struggle is very evident in a South African town hall debate show in 2014 (“Big Debate on Racism”). In the show, opinion leaders across a variety of industries and races debated why the dream of the “rainbow nation project” has seemed to fail. The debate illustrates the continued need for finding productive ways to discuss racism.

In contrast, CRT may critique Mandela’s focus on agency as inadequate and suggest attacking the ideological scene of racism itself. CRT maintains that racial gaps have not improved in the United States even with legislation from the civil rights movement (Delgado and Stefancic 41). Therefore, CRT advocates for political and educational structural reform (Bernal 110-111; Hamilton 87-88). However, CRT’s focus on group-based power structures are critiqued as encouraging revolution (Rufo) and fracturing society (Reilly 659). It is possible a focus on just the scene of racism does not yield long-term solutions of unity and peace.

Perhaps what is needed is a scaffolded pentadic approach, in which pentadic terms are changed in a step-wise process. Instead of assuming there is only one root problem, one can address the issue from multiple angles. For instance, a focus on transforming agency may have been an appropriate first step to allow all voices to be heard, and subsequent efforts should now attend to the scene of racism through education, hold individuals as agents to higher moral standards, and have public leaders implore the purpose of unity. Another strategy could be termed the simultaneous pentadic approach, in which all terms of the pentad are attempted to be transformed on the same occasion. Further research is encouraged to assess the various potential combinations and results of these different approaches.

Finally, combining dramatic frames may offer a creative framework to address racism effectively. In his speech, Mandela uses a comic frame by building universal identification, emphasizing impartiality, and focusing on the foolishness of racist policy. One critique of the comic frame, though, is its inability to address “situations justifying warrantable outrage,” such as Hitler’s actions or the bombing of Pearl Harbor (Desilet and Appel 356). Similarly in South Africa, the tension of wanting rectification—while desiring a unified country—is quite evident (“Big Debate on Racism”). Likewise in the United States, while the causes and solutions of racism are debated, the existence of racial inequalities is well documented and requires a response (Hartman et al.). The other option is a tragic frame. The general tone of CRT in addressing the dire consequences of racism is arguably a factional tragic frame, where all guilt and evil is externalized to another party. Yet as discussed so far, this approach does not provide long-term solutions. Instead of just selecting either a comic or tragic frame, there must be another possibility.

In such situations of warrantable outrage, Desilet and Appel discuss the potential of combining frames by initially using a tragic framing of conflict within a broader strategy of comic framing (356). They provide a notable example from President Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 and 1943 speeches in the wake of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. In 1941, Roosevelt expressed appropriate, tragic rhetoric in condemning the attacks, yet he did not use words to dehumanize the Japanese people. In 1943, while Roosevelt projected victory for the battlefield in a radio address, he still verbalized hope for Germany to rejoin the international community after defeat. Roosevelt’s example illustrates how tragic framing can be embedded in a larger comic frame seeking unity (Desilet and Appel 356-358). In a similar way, it should be explored how combining modes of framing may be used to acknowledge the outrage of racism while also proposing peaceful solutions.

Conclusion

The topic of racism in the United States has fueled controversy and divisive rhetoric as different perspectives, political parties, and theories collide. Burke’s theory of dramatism can play a unique role in this discussion by offering methods suitable for integrating diverse viewpoints and encouraging unity. To Burke, rhetoric is not simply persuasion, but a means toward identification which “seeks to build a community, a sense of oneness amid diversity of conflicting interests and values” (Crusius 28). Through the case study of Nelson Mandela’s 1964 Rivonia Trial speech, this essay demonstrates how pentadic and dramatic framing methods can promote constructive dialogue and creative rhetorical approaches. Clarity and holistic messages are the first step, and it is seen that Mandela crafts a counter-story, creates a juxtaposition of an oppressive present and hopeful future, advocates for a pragmatic transformation through agency, and uses a comic frame to address the universal problem of racism. The pentad is heuristic, allowing for creative ways to address racism from a singular, scaffolded, or simultaneous pentadic approach. Furthermore, combining tragic and comic frames may offer an innovative strategy to rectify racial inequalities while still seeking unified solutions. Future research using dramatism is encouraged to continue the dialogue on how to address the pentadic hand of racism in today’s society.

Works Cited

Anderson, Floyd. “Five Fingers or Six? Pentad or Hexad?” KBJournal, www.kbjournal.org/anderson. Accessed 1 May 2017.

Apartheid.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/topic/apartheid. Accessed 22 Apr. 2017.

Bernal, Dolores Delgado. “Critical Race Theory, Latino Critical Theory, and Critical Race-Gendered Epistemologies: Recognizing Students of Color as Holders and Creators of Knowledge.” Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 8, no.1, 2002, pp. 105–26.

“Big Debate on Racism.” YouTube, uploaded by Big Debate South Africa, 12 Feb. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=jpLFdtSNwpU. Accessed 18 Apr. 2019.

Brayboy, Bryan. “Toward a Tribal Critical Race Theory in Education.” Urban Review, vol. 37, no. 5, Dec. 2005, pp. 425–46.

Brock, Bernard L. “Epistemology and Ontology in Kenneth Burke's Dramatism.”Communication Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 2, 1985, pp. 94–104.

Bruner, Jerome. “Life as Narrative.” Social Research, vol. 71, no. 3, Oct. 2004, pp. 691–710.

Burke, K. A Grammar of Motives. Prentice-Hall Inc., 1945.

—. Attitudes Toward History. 3rd ed. University of California Press, 1937/1984.

—. Language as Symbolic Action. University of California Press, 1966.

Carlson, A. Cheree. “Gandhi and the Comic Frame: ‘As Bellum Purificandum.’” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 72, no. 4, Nov. 1986, pp. 446–55.

“Critical Race Theory.” ASHE Higher Education Report, vol. 41, no. 3, 2015, pp. 1–15.

Crusius, Timothy W. “A Case for Kenneth Burke's Dialectic and Rhetoric.” Philosophy & Rhetoric, vol. 19, no. 1, 1986, pp. 23–37.

Delgado, Richard, and Jean Stefancic. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. New York University Press, 2001.

Desilet, Gregory, and Edward C. Appel. “Choosing a Rhetoric of the Enemy: Kenneth Burke's Comic Frame, Warrantable Outrage, and the Problem of Scapegoating.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 41, no. 4, 2011, pp. 340–62.

Fay, Isabel, and Jim A. Kuypers. “Transcending Mysticism and Building Identification Through Empowerment of the Rhetorical Agent: John F. Kennedy's Berlin Speeches on June 26, 1963.” Southern Communication Journal, vol. 77, no. 3, 2012, pp. 198–215.

Foss, Sonja K. Rhetorical criticism: Exploration & practice. 3rd ed., Waveland Press, 2004.

Foss, Sonja K., et al. Contemporary Perspectives on Rhetoric. 30th ed., Waveland Press, 2014.

Halsey, Max. “How CRT and Classical Liberalism Collide.” Public Square Magazine, 18 Oct. 2021, www.publicsquaremag.org/dialogue/social-justice/how-crt-and-classical-liberalism-collide/. Accessed 14 June 2022.

Hamilton, Vivian E. “Reform, Retrench, Repeat: The Campaign against Critical Race Theory, through the Lens of Critical Race Theory.” William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender & Social Justice, vol. 28, no. 2, 2022, pp. 61–102.

Hartman, Travis, et al. “The Race Gap: Black/White.” REUTERS GRAPHICS, graphics.reuters.com/GLOBAL-RACE/USA/nmopajawjva/. Accessed 13 June 2022.

Horowitz, Juliana, et al. “What Americans see as contributors to economic inequality.”PewResearchCenter, 9 January 2020, www.pewresearch.org/social- trends/2020/01/09/what-americans-see-as-contributors-to-economic-inequality/. Accessed 13 June 2022.

Kuhn, Moritz, et al. “Income and Wealth Inequality in America, 1949-2016.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 128, no. 9, 2020, p. 4.

“Listen: Two Mandela Speeches That Made History.” NPR, www.npr.org/sections/the two- way/2013/12/06/249210908/listen-two-mandela-speeches-that-made-history. Accessed 10 Mar. 2017.

Love, Barbara J. “Brown plus 50 Counter-Storytelling: A Critical Race Theory Analysis of the ‘Majoritarian Achievement Gap’ Story.” Equity and Excellence in Education, vol. 37, no. 3, 2004, pp. 227–46.

Museus, Samuel D., and Julie J. Park. “The Continuing Significance of Racism in the Lives of Asian American College Students.” Journal of College Student Development, vol. 56, no. 6, 2015, pp. 551–69.

“Nelson Mandela.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/biography/Nelson- Mandela. Accessed 10 March 2017.

Nicholson, Christopher. “Saving Nelson Mandela: The Rivonia Trial and the Fate of South Africa (Pivotal Moments in World History) by Kenneth Broun.” Transformation:Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, vol. 83, no. 1, 2013, pp. 122–27.

Ott, Brian, and Eric Aoki. “The Politics of Negotiating Public Tragedy: Media Framing of the Matthew Shepard Murder.” Readings in Rhetorical Criticism, edited by Carl Burgchardt, Strata Publishing, 2010, pp. 270–88.

Piper, John. “Critical Race Theory, Part 2.” desiringGod, www.desiringgod.org/interviews/critical-race-theory-part-2. Accessed 14 June 2022.

Ratcliffe, Krista. Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Reich, David. “How Genetics is Changing Our Understanding of ‘Race.’” The New York Times, 23 Mar. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/03/23/opinion/sunday/genetics-race.html. Accessed 7 March 2019.

Reilly, Christopher M. “Preferential Option for the Poor and Critical Race Theory in Bioethics.”National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 4, 2021, pp. 647–65.

Rountree, Clarke, and John Rountree. “Burke's Pentad as a Guide for Symbol-Using Citizens.”Studies in Philosophy & Education, vol. 34, no. 4, 2015, pp. 349–62.

Rufo, Christopher F. “CRITICAL RACE THEORY BRIEFING BOOK.” www.christopherrufo.com/crt-briefing-book/. Accessed 14 June 2022.

Rufo, Christopher F. “Critical Race Theory.” YouTube, 14 June 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=cfmpnGV0IGc&t=700s. Accessed 14 June 2022.

Rutten, Kris, et al. “The Rhetoric of Disability: A Dramatistic-Narrative Analysis of One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest.” Critical Arts: A South-North Journal of Cultural & Media Studies, vol. 26, no. 5, 2012, pp. 631–47.

Rutten, Kris, and Ronald Soetaert. “Narrative and Rhetorical Approaches to Problems of Education. Jerome Bruner and Kenneth Burke Revisited.” Studies in Philosophy & Education, vol. 32, no. 4, 2013, pp. 327–43.

Smith, Francesca Marie, and Thomas A. Hollihan. “‘Out of Chaos Breathes Creation’: Human Agency, Mental Illness, and Conservative Arguments Locating Responsibility for the Tucson Massacre.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs, vol. 17, no. 4, 2014, pp. 585–618.

Solórzano, Daniel G., and Tara J. Yosso. “Critical Race Methodology: Counter-storytelling as an Analytical Framework for Education Research.” Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 8, no. 1, 2002, pp. 23-44.

Tilli, Jouni. “The Construction of Authority in Finnish Lutheran Clerical War Rhetoric: A Pentadic Analysis.” Journal of Communication & Religion, vol. 39, no. 3, 2016, pp. 41–58.

Tonn, Mari Boor, et al. “Hunting and Heritage on Trial: A Dramatistic Debate over Tragedy, Tradition, and Territory.” Readings in Rhetorical Criticism, edited by Carl Burgchardt, Strata Publishing, 2010, pp. 253–70.

Wagner, Jennifer K., et al. “Anthropologists’ Views on Race, Ancestry, and Genetics.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, vol. 162, no. 2, 2016, pp. 318–27.

Weiser, M. Elizabeth. “Burke and War: Rhetoricizing the Theory of Dramatism.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 26, no. 3, 2007, pp. 286–302.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

- 31583 reads

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 123.72 KB |