There is talk about us, a disquieting chatter. Our bodies are inspected and scrutinized for how we’ve configured our Xs and Ys. Some want to turn us over and examine the dark, mysterious underbelly of the untamed beast. We are craftily categorized: Master and pupil, collaborator and adversary, branded male or female, black, brown, of color, colored. This strategy is used to isolate us when we resist, corral us once we’re broken, divide and conquer, then patch our misshapen bodies back together, for the complete collection holds more value than each piece alone. For their convenience we are rooted, rerouted, deracinated.

Now we are gathered in this classroom, propped up on furniture made from skeletons of trees, ancestral bones. These tables are scarred from years of mistreatment, rage, invalidation, disrespect, and mine, if you peer closely up its leg reads, “fag. you are gay.” There is text about us, a disquieting etching. Who is “you?” And what is “us?” In this classroom I am teacher and you are student and we are excavating ourselves from legacies of shame. But what treasures were buried alongside the bodies of our ancestors.

Ours are bone-deep archives recovered from “exes” and “whys,” nonlinear histories of who we’ve loved and what we’ve questioned or given over to the gnarling, finger-like roots, the jungle trees splitting through stony temple walls. But the chatter persists like white noise and the message is palpable. Some believe we need to be saved, uplifted from our queer and crooked ways. Others aim to pinkwash the Black&Brown off our skin and rescue us from the backwardness they believe we are determined to preserve. Doomed either way, we’ll have to be strategic if we want to survive. And is that what we want—to survive? I think survival is setting the bar too low. Can we be idealistic for one moment, even if it’s fleeting?

I sometimes get asked if I am “out” (as queer) to students in the research writing course I teach, and this question follows me into the classroom like a disquieting chatter creeping through my bones. For several semesters, I have taught this course using a theme that takes up critical theories of gender, and our assigned readings draw students’ attention to a range of queer perspectives that sometimes raise broader questions about LGBTQ rights, visibility, and safety on campus. We pour over the words of Gloria Anzaldúa’s “How to Tame a Wild Tongue” and our student-led discussions bring us to questions such as this: Is she sincerely wondering how best to “tame” a “wild tongue” or is this title a satirical jab? The debate that tends to follow begins with neatly divided assertions, black and white, but fades into ambiguous grays, our words transforming into particles of dust that fight gravity and refuse to settle. Our course texts are not divorced from how we have come to gather in this classroom. For, as Mel Michelle Lewis reflects, “students potentially perceive” her body (“Black lesbian woman”) as “‘embodied text’” that “becomes even more saturated with symbolism in courses that center matters of race, gender, sexuality, and other dimensions of ‘difference’”(34–5). Our bodies, teachers’ and students’ alike, are inspected, scrutinized, turned over and examined symbolically and semantically in countless instances: the moment we use unverified gender pronouns, to name just one instance.

It recently occurred to me how disoriented I am by the question of “outness.” I have been thinking about queer teacher identity for two decades and have only ever (or never not) been out during that time. Yet I have also never stood before my students and made an unsolicited declaration: “I am queer.” If I do not specifically discuss my queerness within the classroom space does this mean I am closeted by omission? This very point has been a common subject for debate taken up by composition pedagogues such as Harriet Malinowitz, Mary Elliot, Karen Kopelson, and Jonathan Alexander, among others. On the one hand, I hear arguments about the importance, if not the imperative, to declare our queerness in an explicit fashion to students; on the other hand, I hear contentions about the advantages of taking a subtler, more context-driven and individualized approach. In any case, there is no monolithic student-audience poised to receive our declarations. I find that some students read queerness on my body or through my interests and alliances while others do not. Does this reality define me as “out” to some students and “in” to others, queer to some but not to the rest? And are there only two positions in the mix—out/in, queer/non-queer? The trouble with pairing and polarization does not end here, for as Isabel Nuñez explains, “sexuality is part of who we are, and it does not go away when we enter our classrooms” (85). This point rings especially true as I examine the etched declaration: “fag. you are gay.”

One of the greatest challenges I face when thinking about my queerness in the classroom concerns the ways in which I am often asked to speak from the standpoint of a queer teacher or a brown teacher but rarely both at once. I find that in situations where “both-at-once” is encouraged and permissible, a conjunction is tacitly expected; I must speak as a queer and brown teacher. I presume the reason why this happens is related to what Lewis surmises as “an act of ‘excess’”—that “coming out in the classroom” as a “Black lesbian” becomes, for her, “a performative act that explodes the nexus of ‘that which is Black’ and ‘that which is queer’” (36). I am troubled by the patterns of coupling and dichotomization I must navigate linguistically but have not grasped how to address this, for the term “queerbrown” does not seem adequate either. Identifying myself as a “queerbrown” teacher limits my desire to peel back the unending layers of critical consciousness, to think simultaneously and inseparably about sexuality, race, gender, class, ability, age, size, citizenship, “pedigree,” and the like.

On a broader scale, analyses of queer teacher identity can afford to be more deliberately resistant to discussions of queerness as separate from race in order to reexamine, problematize, and value our pedagogical performances as a dynamic, ever-evolving process. In other words, the onus of examining shared tropes and discourses of a queer, racialized teacher-subject should not fall only upon those of us marked “of color.” I begin by revisiting earlier concerns raised by composition pedagogues (Miller, Kopelson, Scudera) on the subject of queer teacher identity and consider if and how these theories shape the current conditions I face as a “queerbrown” composition teacher. In order to see these conditions through a lens that is sensitive to the false dichotomies of “in” and “out,” I intertwine my analysis of “the closet” with excerpts from an open letter to my Black&Brown Queer identified students. I argue that the closet often circulates in ways that limit our discourse about queer teacher identity and call for a pointed analysis of queerness that can be mistaken, “unread,” and, thus, closetized. I take up the term “closetized” as a way to describe the phenomenon of closetedness imposed on (teacher) bodies. Because as writing teachers we often ask students to wrestle with relationships between language and identity while encouraging plural ways of reading, I redirect these goals toward a theoretical reflection on the multidimensionality of teacher identity.

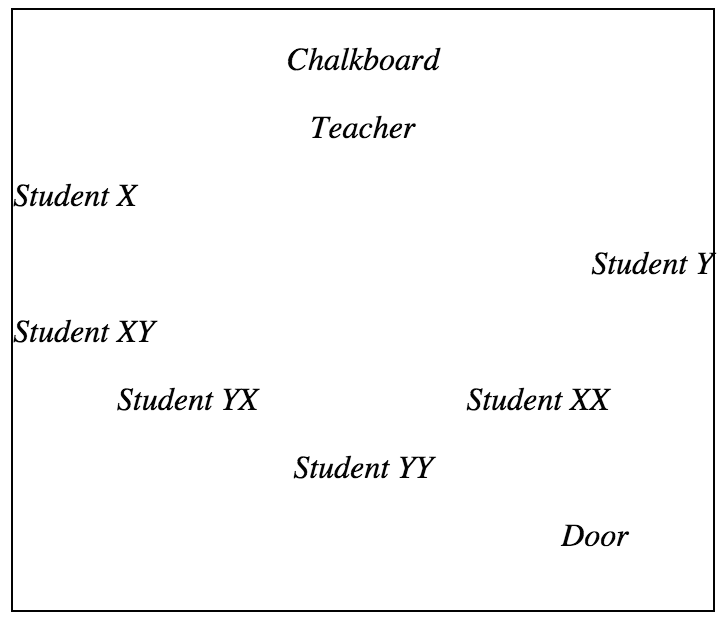

When would you like me to tell you I’m queer? Before we go over the syllabus on our first day of class, as we trace the skeletal structure of the course? Or by week seven, when the foundation has set and our roots begin to sprout through the ivory floors and stony walls, and we’ve collected and categorized bits of information about each other:

|

Teacher |

Student Y |

Student X |

Wears: |

Skirts or dresses, floral tattoos on arms |

Green or blue nail polish, Syrian flag stitched into denim jacket |

A red hat, koi fish tattoo on wrist |

Brings: |

Blue Benares scarf |

Prayer beads |

Foods to share |

Has referenced: |

Gloria Anzaldúa’s “Speaking in Tongues” and Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein |

bell hooks’ “Feminism: A Movement to End Sexist Oppression” and Lady Gaga lyrics |

Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider and online astrological predictions |

Are these bits of information decoding a secret language? I don’t know if you’d like me to tell you I’m queer or if I’m communicating it to you already. Perhaps there aren’t just two possibilities, and in any case, it isn’t easy to pick up on all the cues. I don’t know how to read your stony expressions during class so why should I assume I’ve made myself any more transparent? Student X, you contribute eagerly to the day’s discussion, then tell me afterward that your fear of making sentence-level “errors” prevented you from completing the writing assignment that was due. Student Y, you seem disengaged, then tell me you spent hours the night before watching a Wong Kar Wai movie marathon that wouldn’t let you stop for sleep. Grammar leaves us frozen. Movies make us insomniacs. We gather in this classroom poker faced yet searching for auspicious signs that things will work out as we hope. What is in our stars this semester, Student X?

They often suggest that you cannot read me at all, that Black&Brown “communities” don’t see queerness because we are quantifiably more homophobic and heteronormative than the rest. So, I thought I’d ask you directly seeing as I tend to favor transparency . . . Or do I? What does it mean to be transparent? I don’t mind ambiguity around Xs and Ys, Blackness and Brownness. But what about you? When was the last time someone asked you directly what you’re “reading” or how you perceive teachers in the classroom?

One of the course goals we discuss on our first day is how to practice habits of reading throughout the most seemingly mundane daily activities—how to imagine our surroundings as an unending text. We consider whether it’s possible to distill assumptions and judgments from initial impressions. As the weeks pass, what are your impressions? Perhaps this is not for me to know. This may be asking you to share something private. There’s likely a difference between personal and private, another pair we ought to analyze. We’re getting good at this business of dissection and regrouping, bonding, separating. Master and pupil, isolated and corralled. They taught me how to do this with words and now I’m teaching you, but here we are going about it with more questions than instructions.

This anecdote is personal, not private: They taught me how to take a pair of synonyms and find the nuanced differences. I had a queer way of expressing myself, stuck in the deviant language practices I learned from my ancestors, the “illiterate” savages, dirty and godless. My roots have a primal grip; we were a people of queer tongues, communicating with peculiar, disorienting words. I carry this genetic memory in my bones. At school, they replaced my thesaurus with a dictionary when I confessed my secret—I was trying to write using novel and nobler words than the ones I actually knew—that my thesaurus was a suit of armor. In order to inspect me they had to access my skin, seize the armor, strip and scrutinize me, peer into the Xs and whys. The armor is gone, and now here we are (you and I), pairing and dividing, and I’m wondering if you think there’s an artful advantage to reading like the masters. (How) are we reading and isolating each other?

I am trying to locate a queer lineage and in doing so find that teachers have long been divided on the imperative of coming out in the classroom, whether to come out at all, how and when to do it. We pair and divide ourselves on this subject. Queer pedagogical theories lend themselves to constellation-like patterns that reflect the broader social contexts in which they have emerged: In the mid 1990s, Elliot draws from Malinowitz’s claim that coming out to students is useful for “‘divesting those students of their ignorance and their entitlement to prejudice’” (qtd. in Elliot 706). Elliot posits her preference for coming out “spontaneously to students at the ‘golden moment,’” that is to say, moments that “occur during class discussions and thus provide a relevant context for self-disclosure” (704–5). Almost 20 years later, Domenick Scudera’s “Teaching While Gay,” continues the conversation about how LGBTQ teachers negotiate identity politics in the space of their college classrooms. Scudera describes a familiar tension between encouraging students to speak openly about their views and deciding what counts as intolerable bigotry, hate, and homophobia. Both explicitly and implicitly, Scudera raises larger issues of (LGBTQ) teachers’ responsibilities, academic freedom of expression, and so-called “safe zones.” I am struck by Scudera’s reflection on wanting his students to “speak freely” while questioning where to set “limits” on their views:

If one of them expressed a racist opinion, say, during a discussion of the work of Frederick Douglass, I would stop the class immediately and face the issue directly. Yet oddly, when approaching a text like Fun Home, I feel compelled to make my students feel comfortable in expressing any opinion on the subject of homosexuality And [sic] that may mean that their thoughts oppose the very life that I am living. If I were Jewish, would I create a safe environment for anti-Semitic opinions to be expressed when reading chapters from Primo Levi's The Drowned and the Saved? If I were female, would I allow my students to belittle women during a discussion of Elizabeth Cady Stanton's writings? No. I would not tolerate misogynist, anti-Semitic, or racist talk in my classroom. Yet as a gay professor, I encourage my students to share their thoughts against homosexuality.

The questions Scudera raises about student expression and censorship are honest and ethically conflicting, and they compel me to revisit earlier works by Richard E. Miller and Karen Kopelson, works that reimagined a space for pedagogues to discuss LGBTQ teacher identity in the context of teaching composition. In “Fault Lines in the Contact Zone,” Miller’s questions about how to address blatant homophobic hate speech in student writing along with Kopelson’s strategies for “performing neutrality” in order to quell student resistance offered a generation of scholars like me a launching point to debate and critique how teacher identity functions in writing courses. Kopelson’s “Rhetoric on the Edge of Cunning” describes neutrality as “the very ‘cornerstone’ of an elitist, exclusionary, masculinist ‘Western intellectual tradition, established by white, heterosexual men’” and suggests that performing neutrality “may” permit “teachers to work with and, in many cases, work against their own identity markers and, in that process, to work with and against student antagonism to identities and issues of difference more generally” (121, 122). I am disinclined to describe any position—“cunning,” “satirical,” or otherwise—as “neutral.” Furthermore, I am unlikely to prejudge a body of students as homogenously resistant and follow up by catering to their imagined perceptions.

Just as there is no consensus on whether and when to tell students we are queer, it can be difficult to know if and how we are or will be inspected, scrutinized, and/or celebrated. Lewis explains that “asserting queer [instructor] identity may be perceived by students, other faculty and administrators as an act of inappropriately sexualizing the classroom,” but this observation functions as a reality rather than a warning, for examining “the subject matter through the sharing of embodied knowledge at the nexus of race, gender, and sexuality is critical” not only to a “feminist intersectional analysis” but also to “a framework that appreciates these intersectionalities “as a part of the performance of pedagogy” (36–9). Knowing how we are read eludes us to varying degrees; for some, it may be unknowable. Nevertheless, the question of whether or not I am “out” leaves me asking if and how students read my allegiances. I wonder if some students expect me to support a certain kind of academic gatekeeping or share in a circulating perception of our college as a remedial place for those branded “at-risk” and “underprivileged.” I feel sensitive, if not defensive, about the contradictions I might be perceived to embody as a “queerbrown” academic, and this discomfort is certainly mine with which to grapple. I have a responsibility to work through this and as I do, allegiance reveals itself as a key piece; it is important to me, regardless of what students and colleagues do or do not perceive, that I remain committed to struggles against oppression, or as my students and I have called it in our class discussions, “The Struggle.”

Are we supposed to have a shared secret language? Shared maybe, but not secret because secrets might provoke resentment and suspicion. Student XY, you describe the anger and shame you feel toward the conditions of “our people.” “Y’know, Professor. OUR people.” We labor over the meanings of words—differentiating, discriminating. Yet we’ve never discussed “The Struggle” and carry on as though we share an understanding of this term. Would you like me to define the “we” I am constructing and the “them” I am invoking or do we have a shared understanding here, too? Them/us is both dangerous and strategic. How do we know when to cross the line or when we are (un)wittingly doing so? From pupil to master, we find ourselves crossing illusory boundaries, sometimes from master to pupil again. “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (Lorde 112). And what of those who’ve crossed from field to house?

It’s no secret that just as I am always out, I am always committed to The Struggle. At times I wish this were obvious, no declaration necessary, and I suppose this is because your affirmation would mean something to me. But it’s not your job to affirm me. Perhaps my commitment is already obvious and I alone am missing the secret codes and cues. My allegiances are not necessarily disconnected from who I am, and by saying this I’m not alluding to some authentic core or essential self. I am talking about an inherited legacy, a genetic memory, the stuff we sometimes know but don’t know why we know it. For me it’s the awareness that my lineage has been revised, weeded at the root, and fictionalized. My ancestors were divided (and sometimes divided themselves) into tribes. Ours and theirs: “not ours/like ours.” Ours were warriors, artists, and dancers, whose traditions were quashed in conquest and robbed amid the traumas of ethnic cleansing. Sanitation and sanity fold neatly together like two halves of a mango. Some tried to rise up as rebel outlaws. Rise and fall—that is what marks an empire. That was before the tree roots clawed through stone ruins to reclaim their own land.

Now, they suggest that I “get in touch with” my culture and be proud of my roots, for that is what it means to overcome internalized oppression. Get in touch but don’t touch too much because it wouldn’t be wise to rise and fall back into backward ways. They tell me they’ll teach me which move to make, what to treasure, how to read because they are now the keepers of the empire in its dusty jungled rubble. They are the keepers of our forgotten traditions:

Do Touch: |

Don’t Touch: |

“Yoga” classes for campus community |

Profits made on (mis)appropriated customs |

“Ethnic” artifacts and apparel |

Laws on kirpan in public schools |

“Our peoples’” literature |

Canonical requirements |

They want me to think about what I am modeling in the classroom because it’s important to lead by example, to model pride and joy, not shame or bitterness. On some days, though, pride, shame, joy and bitterness are twisted and tangled so tightly that the only solution is cutting them out at the roots.

It is a struggle to trace roots that have clawed themselves through walls of stone, spread like fingers, at once sinister and desperate to survive. Some roots are broken, gutted at the flesh, bones exposed, and others are velveteen, curious, stretching cautiously into the unknown. I see root-like veins in my face, under the skin, a layered collage of ancestors splitting through my stony expression. Not surprisingly, I have yet to be asked if I am out to my students as brown. My performance of queerness is apparently less obvious than the brownness of my skin. As such, my brownness signifies less ambiguity and thus leaves no real opportunity to “come out as brown.” I am uneasy with this explanation because performing brownness, for me, is also a multifaceted reality. I am reminded of Malcolm X’s 1963 speech in which he distinguishes between another pair—“the field negro” from “the house negro ”—explaining that the construction of a “twentieth-century Uncle Tom” is so closely allied with (or subservient to) his master that “if you say you’re in trouble, he says, ‘yes, you’re in trouble [and] doesn’t identify himself with your plight whatsoever” (“The Race Problem”). “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (Lorde 112). While the distinction Malcolm makes emerges from a vastly different historical context than that of my own lineage, on a symbolic level it resembles the polarized roles that shaped my immigrant family and communities. We were divided (and sometimes divided ourselves) into categories of “assimilationist model minority” and “traditionalist rebel outlaw,” the former acquiescing to the demands of colonizers and the latter armed in resistance against colonial pressures. Of course, the binaries do not hold, they fall apart, one a part of the other. And as far as my own brownness is concerned, I am out as brown to my students in the same way I am out as queer. That is, I have only ever and never not been brown.

(When) would you like me to tell you I’m brown? Not the kind of brown that will sell you out inside the ivory tower and dodge you on the dusty streets. The kind of brown who is having a paradigm shift, a queer experience, a moment of affirmation just being in this classroom with you. I was raised to think of “model minority” as a compliment. Now I feel its burning insult. The world of models is a competitive one and it sets us up to fight each other for a scrap of recognition. A model for whose standards and consumption? These are questions my ancestors have taught me to ask. “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (Lorde 112).

Student YY, I notice your fabulous green nail polish as you raise your hand. You ask me where I got my blue Benares scarf. We talk briefly about the detailed emphasis on food in Chungking Express. You show up in your small group conference wearing high-heeled shoes. I admire their design. “Today is national coming out day,” you say, “and I’m coming out on campus.” Your peers and I beam and affirm you. Affirmations and compliments are not the same thing, and although we’ve never explicitly discussed the difference, you’ve taught me and I’ve learned through the act of sharing language. We are both teachers and students in this moment, this one, hyperbolically ideal and fleeting instant.

Now, for the first time I am not The Brown Face in the classroom, I am just another—even as a (brown) teacher. Just another brown body exiting the train, walking up the stairs and down the path to campus. When the pack of police officers scrutinize our faces on the subway platform, their gaze sweeps across mine. They are looking for dirt in the pile. Inspecting our underbellies. I am just part of the pile: “Not You/Like You” (Trinh). When I was stopped by five cops in the train station for a “random” search, I wished from a place of fear and humiliation that they would read me: “model minority.” I caught myself immediately. Model for whom? At that sick-in-gut moment, the conversation shifted to a lighthearted discussion, compliments directed at the rich, blue color of my scarf, and I realized that perhaps “model minority” was how they decided to read me and I alone had missed the codes and cues. Let me read my own rights: Why should I get to walk the line between model minority and rebel outlaw whenever it’s convenient, even if only to protect myself in a given context? I haven’t earned any right to do this, it’s about the privilege I hold.

I routinely learn about the ways in which being perceived, albeit problematically, as a “model minority,” especially in terms of race, gender, and class, grants me certain kinds of access. Joycelyn Moody describes the multilayered complexities involved in finding and being with community:

I want to avoid ranking oppressions or claiming some oppressions graver than others. Something stops me. […] I know that ain’t no body like a black body, that black bodies are subject like no others to unspeakable tortures. And no, I do not mean an expansive ‘black’ body—as in, say, the postcolonial black body of India, nor ‘black’ as a category that contains all nonwhite groups, as in ‘colored.’ I mean of African descent. Period. (165)

Historicization is key here; one of the most important aspects of Moody’s claim is that underrepresented individuals and communities can benefit from listening across lived legacies and experiences. Her point here underscores the impulse to find shared grounds on which to establish community and the material challenges this impulse can pose. Although many of our affiliations and desires are interconnected, we sometimes discover that our roots have clawed deeper into certain aspects of our lives, and the commitment to honor ourselves as whole people can feel like a heartbreaking endeavor. At times, my students will argue that experiences of oppression are quantifiable and permit us to draw conclusions about “who has it worst.” These are debates I neither advocate nor censor. Instead, I assert that it is important to know our collective and individual histories in order to examine where each one of us stands today.

From a pedagogical standpoint, it can only enrich our classroom instruction, individual and collective struggles, or participation in The Struggle to reflect on where we hold privilege. We have a responsibility to examine even if and how The Struggle is ours in which to participate. For, as Tonia Bryan reminds us, we cannot afford to gloss over the ways in which we are not positioned equally: “WHAT DO YOU MEAN YOU’RE NOT A ‘LESBIAN OF COLOUR?’ you asked when I refused to go to a retreat for lesbians of colour. When they had that big feminist conference in Africa. You know, the one in the eighties where the BIG GIRLS CLUB decided that ‘OF COLOUR’ would be our name? WHO WAS CLEANING THE TOILETS?” (68). The hidden labor of scrubbing and bleaching haunts me to the bone. I imagine those who have tried to scour the message written up the leg of my desk: “fag. you are gay.” Carrying this image is not meant to absolve us from the privilege of indifference.

We might have to check our language, find new codes and cues, tell some secrets not necessarily out of a desperation to be absolved but to understand what is happening in our guts. To remind ourselves what it means to have guts and that we are not indifferent. I have a feeling that we are wise beyond our years and our guts have a private map that can tell us where to go from here, how to navigate the jungle so that we can visit our own ruins. I’ve sometimes wondered why the expression is “wise beyond our years” but not “beyond our ears.” Both seem accurate and probable. We don’t have to hear to know what’s being said. We must access the language we have learned for survival, the one Anzaldúa calls “a patois, a forked tongue, a variation of two languages” (Borderlands 77).

Students X&Y, while you’re writing individually or working on peer review, my gaze follows the circle of wooden desks pushed along the perimeter of our classroom. These desks came from curved trunks of trees, now transformed into 90-degree angles, severe edges and stark lines. They are bones that lost their roots, and we are trying to curve them back to a lively form. It’s a misshapen, incomplete circle, large gaps to each side of my desk. Student XYX, when I ask you to move in closer, you inch up reluctantly and I don’t pursue it. Perhaps this is a gesture of respect, like how you insist on calling me “professor,” a traditional holdover that defines me from you. Then again, we are not the same.

We’ve been taught the language of divide and conquer and memorized it as a means of survival. Teacherness from studentness, a strategic separation, or something akin to the title of the Trinh T. Minh-ha essay we just finished reading: “Not You/Like You.” Remember how we lingered on this passage: “Those running around yelling X is not X and X can be Y, usually land in a hospital, a rehabilitation center, a concentration camp, or a reservation. All deviations from the dominant stream of thought […] can easily fit into the categories of the mentally ill or the mentally underdeveloped” (215). Remember how we sat in heavy silence, reminded of the times we’ve been labeled academically “remedial” (215)? We were corralled, broken, tamed into performing a “sanitized sanity.”

Maybe it’s something else, something more Frankensteinian that compels you to keep some distance. I might ask you to contribute to class discussion, to exhibit what I believe you know, to perform an intellectual tap dance with me to mark the milestones we’ve crossed. Perhaps it’s simply logistics, it’s tough to see the chalkboard when your back is against it. They are but two small gaps distorting our already imperfect circle, collecting chalk dust as it settles to the floor. We’ve made a half-hearted loop contained by the square-shaped room. Four white walls and four wrong angles (for our purposes anyway):

The gaps disappear whenever I take a different seat, one away from the chalkboard, but they are symbolically still present. We are different from one another, every body in this room. Our Xs and Ys and Black&Browns. Sameness was never the goal. At times I try to talk about us as a “classroom community,” but that’s not quite adequate either. We are different from one another but not indifferent: “Who cleans our classroom?” We cannot discuss The Struggle in abstraction from the dark hands that labor in the dark hours of the night, the roots that split through the earth into our ivory classroom, clawing through this graveyard of trees and scouring “fag. you are gay.”

The leg of my desk, “fag. you are gay,” is simultaneously public and hidden. I scrutinize this text, its lower case letters and periods, a grammar uncensored, frozen. I long to write back: “You don’t have to tell me twice.” This is my little inside joke but only I am in on it, private and personal. Unless, of course, my students have noticed the leg of this desk, read the message, and read me. Could my joke be out? Eve Sedgwick’s work on establishing the closet as a site of knowledge and political consciousness is useful to theories and critiques of how queer teacher-bodies are constructed/positioned/erased within writing classrooms. This work compels me to ask how the closet functions in the lives of teachers who feel tested and limited by dichotomous “in/out” and “queer/non-queer” modes of communicating. Building on Sedgwick’s assertion that “‘Closetedness’ itself is a performance,” I add that closetedness can be abstract and concrete, metaphorical and literal, rich, nuanced, pejorative and yet beautifully strategic (3). For as Steven Seidman points out, “closeted individuals remain active, deliberate agents” who “make decisions about their lives” and “forge meaningful social ties,” (30, 31). Seidman is also careful to explain that “it is perhaps more correct to speak of multiple closets:” there is no one experience of closetedness even if our narratives and histories share resemblances (31). Sameness was never the goal.

For teachers who are out but read as non-queer, agency seems to be held by particular audiences who, upon learning we are queer, react as though we have just come out. In this context, the audience becomes the central subject around which “inness” or “outness” revolves. This issue of agency is magnified whenever celebrities are said to have come out in the media. Celebrities, not unlike teachers, are frequently referenced in debates about responsibility, example-setting, and modeling pride. If and when we publicly comment on an aspect of our queer lives our comments are constructed, if not rebranded, as a public “coming out.” In some instances we are offering exactly that – a public revelation aimed at circulating information previously guarded as private. But it is also plausible that the individual is in fact out and open about their queerness and through a candid remark or gesture makes the audience suddenly privy to their queerness, an audience who, for any variety of reasons, was not previously “in the know.” It is not necessarily possible (or desirable) to control how we are read and perceived, even if for some individuals there is little ambiguity around their queerness. According to Tony E. Adams, “in order to ‘come out’ one must first somehow ‘go in,’” and it is worth examining what this means for those of us who have, for long stretches of time, “only ever, never not” been out (21). Somehow, we remain at risk of being closetized.

I have been searching for the appropriate term to use to describe public or politically sanctioned forces that “closet” (as a verb) certain individuals. “Closet” alone, even as a verb, may be unsuitable for those of us who have “already” come out and by having done so believed the act to be somehow linear. We have followed a scripted trajectory: We were closeted, then we came out, and so this after-the-fact public construction is more accurately a re-outing. We become re-closeted, encloseted or closetized by being mistaken and unread. “Unread” is a term I prefer over “unseen” and “unheard” because reading is not limited to those who can see and hear. Let me emphasize that not everyone can be closetized; there are some for whom queerness is not ambiguous. Or, is queerness, perhaps, always ambiguous?

We’ve arrived at a point where we need to discuss the pervasiveness of ableist language in how we communicate experiences of oppression: Some of us are troubled by our “invisibility” and unmet desires to be “seen” and “heard.” Student XX, I notice that you’ve begun to apply the term “reading” to everyday situations like reading people on the subway or customers at your workplace. You stop yourself midsentence to question this act of reading: “Wait, in a way I’m making determinations when I read people and how do I know these aren’t just assumptions and stereotypes?” Reading, as we are using this term, is political. It isn’t free of ideology and you make an excellent point; it’s a disorienting cycle to be read and unread in the same instant, to be, in fact, misread. Reading, and more broadly literacy, is complex. It is entrenched in hierarchies and gatekeeping mechanisms and yes, we need to be reflective.

Some of us are always read as queer, never misread. But “always” and “never” are absolute traps from which we need a “patois” to release us. And if our goal is to learn different ways of reading does “misreading” have a place, too? Could all readings be misreadings, even if all readings are not equally suitable? I fear that it’s these self-conscious uncertainties that make them think we are imprisoned in a closet, quarantined from the bright, righteous light. Could this be why they want to save and rescue us from the confines of our dark, oppressive paradigms? I have chased that light beyond the closet door in a desperate and futile pursuit. I wonder if I’m ever plainly out or if I simply pass from one dark closet to another. After all, to enact the false voyage of dark to light merely replays the master narrative—dark, tattered, ignorant savage transformed at the feet of the bright, starched, righteous, savior, everyone promising to save and be saved.

My own closet is dark indeed, made so by the brown-skinned women who fill it, the women who gendered me in those sequined Benares silks that sparkled when light entered from cracks in the door. My closet is a dynamic space of action and interaction, a complicated legacy of repression, self-hatred, and joy, all woven, stitched, and pressed into brocade designs. These are the women who taught me to take pleasure in bold, imported fabrics, originally spun at the hands of our “compatriots.” For me these women modeled womanhood, living emblems of civic pride, nationalism, custom, and tradition, with jewels dripping gold and shoes most certainly not meant for walking. These women were an embodiment of femininity, arriving at gatherings in ornate saris and jalabiya, carrying vats of homemade curries. They personified a perfumed sisterhood: wife, mother, daughter and auntie, ladylike, heteronormative and homosocial just as their versions of God commanded. But within the closed-door mutterings to which I was privy, their perfumes masked another reality. They meticulously archived anecdotal evidence about who was good and who was bad. Bad girls outfitted us with tools to measure the good, and good girls served as moral models for the bad. There was no gradation between pedestal and peril; the boundary was a cliff with a 90-degree drop and women were falling right before our eyes. Femme Fatales marked XXX. Falling from all the wrong angles.

When I examine “the dark space” of my closet, I find the contradictions overwhelming and absurd. In Kami Chisholm and Elizabeth Stark’s 2006 film FtF: Female to Femme, Masha Raskolinkov explains that ideals of femininity are truly unattainable. One might strive toward such ideals but can never reach or fulfill them, for femininity is, in many ways, an abstract, impossible myth, although to perform and play at femininity can be, for some, a savvy, delightful, even ironic act. For me, femme can be a self-conscious performance, a deliberate masquerade, a costume, a pleasurable, playful outlet, as well as a gut feeling, corporeal experience, an urgent reality and much more: “femme is the trappings of femininity gone awry, gone to town, gone to the dogs. Femininity is a demand placed on female bodies and femme is the danger of a body read female or inappropriately feminine. We are not good girls—perhaps we are not girls at all” (Rose and Camilleri 13).

I take up femme to challenge the notion that artifacts, characteristics, and actions traditionally associated with femininity (and thus, deemed oppressive) are inherently demeaning and sexist; the trouble is that we have learned to attach sexist attitudes and perceptions to these artifacts in the first place. The perceived power (or powerlessness) of applying nail polish, for example, is of our own making. Rose and Camilleri offer their description of femme as a somewhat elusive term: “Femme is inherently ‘queer’—in the broadest application of the word […] Released from strictures of binary models of sexual orientation and gender and sex. Released from a singular definition of femme. Released from the ‘object position’ where femme is too often situated” (12). The perception of femininity as contradictory to queerness wavers as a misguided yet pervasive reality. I am familiar with the ways in which dominant receptions of femme grant a female, brown, woman-identified subject like me certain kinds of cisgender privilege, as well as how these privileges play out in my classrooms and the workplace at large.

The absurd contradictions of “normativity” and queerness as well as judgments of “good” versus “bad” are routinely projected onto queerbrown teacher and student bodies. Black&Brown individuals are often expected to “behave” in ways that confirm or downplay their Black&Brownness, queer individuals are often expected to act in ways that confirm or downplay their queerness, and gender is sometimes the tool (or scapegoat) used in assessing if/how these expectations are met. Do you dress this way because you’ve acquiesced to the demands placed on Black&Brown women—the pressure to manicure your appearance? Or is this a demonstration of some meta-awareness, an act of resistance in fact? Do you dress this way in defiance of stereotypes or is this a calculated display of queerness?

I scan our imperfect circle as the class discussion continues. Student YY, I can tell you are being cautious with your language, critical and attentive while trying to express your ideas in a meaningful way. I admire that about you. You are sensitive to those receiving your words. You mention that you’ve been disparaged for saying “the wrong thing” or using “the wrong terms.” In some ways I can relate to that. Setting words down can be a terrorizing act. We cast words into a torn up space between the desire for expression, panic of surveillance, and fear of misdirected targets. These are the lingering traumas of being corralled, our roots clawing through, breaking off, digging upward. But for better or for worse, we are in no way alone. Perhaps you and I are learning to walk that 90-degree edge between self-expression and self-censoring and this may be our lifelong endeavor. Or maybe we’ll learn to reconcile the two by forging a “patois” with confidence.

Whenever you’d like me to tell you I will. As the weeks pass, we might establish greater trust in the process of reading, excavating, separating, rerouting. For the moment, I’m writing to you in the epistolary tradition of our ancestors, Lorde, Anzaldúa, Bryan, among others, whose tenderness, honesty, and unapologetic rage sustains and motivates me. I want to keep alive the epistolary tradition (a queer tradition?). I want to use it to queer affect. I want to include you in this discussion of teacher identity, to cross some lines constructed to divide me from you, to let my thoughts, my feelings out of my closet. For me, letters are usually personal, even when they are formal. In this one, I feel vulnerable and restrained. I am sincere and false. It is a self-conscious exercise, serious and farcical, an ironic ruse, the artificial separation of theoretical reflections and italicized confessions. Here, I am “walking the razor’s edge” (Bryan). This isn’t the letter I would write if no one but you were reading. That letter would, perhaps, remain unread.

Works Cited

Adams, Tony E. Narrating the Closet. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2011. Print.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999. Print.

—. “Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to 3rd World Women Writers.” Readings in Feminist Rhetorical Theory. Eds. Karen A. Foss et al. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2004. 75–84. Print.

Bryan, Tonia. “Walking the Razor’s Edge: An Open Letter to My Honey.” Queering Absinthe 9.1 (1995): 67–73. Print.

Chungking Express. Dir. Kar Wai Wong. Jet Tone Production, 1996. Film.

Elliot, Mary. “Coming Out in the Classroom: A Return to the Hard Place.” College English 58.6 (October 1996): 693–708. Print.

FTF: Female to Femme. Dir. Kami Chisholm and Elizabeth Stark. Frameline, 2006. Film.

hooks, bell. “Feminism: A Movement to End Sexist Oppression.” Feminist Theory Reader. Eds. Carole R. McCann and Seung-Kyung Kim. New York: Routlege, 2003. 50–56. Print.

Kopelson, Karen. “Rhetoric on the Edge of Cunning; Or, The Performance of Neutrality (Re)Considered As a Composition Pedagogy for Student Resistance.” College Composition and Communication 55.1 (September 2003): 115–46. Print.

Lewis, Mel Michelle. “Pedagogy and the Sista’ Professor.” Sexualities in Education. Eds. Erica R. Meiners and Therese Quinn. New York: Peter Lang, 2012. 33–40. Print.

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider. Berkeley, CA: The Crossing Press, 1984. Print.

Miller, Richard E. “Fault Lines in the Contact Zone.” College English 56.4 (1994): 389–408. Print.

Moody, Joycelyn K. “For Colored Girls Who Have Resisted Homogenization When the Rainbow Ain’t Enough.” When Race Becomes Real. Ed. Bernestine Singley. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2002. 159–71. Print.

Nuñez, Isabel. “Introduction: Teaching as Whole Self.” Sexualities in Education. Eds. Erica R. Meiners and Therese Quinn. New York: Peter Lang, 2012. 85–87. Print.

Rose, Chloe Brushwood, and Anna Camilleri. Brazen Femme: Queering Femininity. Vancouver, B.C.: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2002. Print.

Scudera, Domenick. “Teaching While Gay.” Chronicle of Higher Education. 9 May 2013. Web. 11 August 2013.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. “Epistemology of the Closet.” The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader. Eds. Henry Abelove et al. New York: Routledge, 1993. 45–61. Print.

Seidman, Steven. Beyond the Closet. London: Routlege, 2002. Print.

Trinh T, Minh-ha. “Not You/Like You.” Readings in Feminist Rhetorical Theory. Eds. Karen A. Foss et al. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2004. 215–19. Print.

X, Malcolm. “The Race Problem.” African Students Association and NAACP Campus Chapter. Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI. 23 January 1963. Web. 26 August 2013.

Young Frankenstein. Dir. Mel Brooks. Twentieth Century Fox, 1974. Film.