The fetish status of the archival object, or rather the reverence accorded to the archival object by researchers, relates to its status as a primary artifact that authorizes the making of new disciplinary or field-specific knowledge.1 What does the field of rhetoric and composition make of researchers who baldly announce desires to work with texts that are “hardly the kind of digestible work found in a traditional composition reader” (Faunce 352)? My essay attends to an understanding of archival material as fetish object. In agreement with Charles Morris, III and K. J. Rawson’s claim that “archival queers must rhetorically induce and construct queer mnemonic socialization in alternative contact zones and counterpublic sites and subcultural spaces,” I conclude that embracing the queer pleasures of the archives must be understood as a vital aspect of queer existence both theoretically and practically (86). With considerations of Jonathan Alexander and Jacqueline Rhodes’s point that the argument against valuing queer writing and rhetoric is one that entails the erasure of queer histories, possibilities, and lives and Mathias Danbolt’s point that minoritarian subjects have never had a privileged relationship to cultural production through official archives, I assert that queer rhetoric’s strength lies in its commitment to representing embodied desires and corporeal experiences that fall outside of the “specter of normalcy” (Rallin 156). My desire to touch queer history, as I explore it in this article, involves engaging the playful tension between the object of my desire’s absence and my longing to conjure his presence.

When I traveled to the David Wojnarowicz Papers, as part of my doctoral research in the field of rhetoric and composition, my criteria for choosing from among the 175 boxes was that the artifacts I selected appeared to be doing explicitly queer rhetorical work. Regardless of whether Wojnarowicz is remembered as an outsider artist, a writer, a public intellectual, a musician, an AIDS activist, or an anti-censorship advocate who fought for freedom of expression during the Reagan-Bush era, or as “the iconic Angry Gay Man” (Carr, “Portrait” 85) who careened off the cliff of history as an entire generation disappeared due to the AIDS epidemic, his significant place in American aesthetics and politics is evident from his continual provocation and disruption of dominant cultural assumptions. Indeed, I was overwhelmed by the volume and scope of Wojnarowicz’s efforts to claim space for and with other like-minded queer, outsider, and performance artists. My dissertation committee gave me fair warning that I would likely want to drag a cot into the archive once I began. To be sure, I became so engrossed while reading Wojnarowicz’s diaries, which have since been digitized, and engaging his artifacts, correspondence, writing, and artwork that I wanted to spend all of my waking hours at New York University in the Fales Library reading room and would have were it not for the fact that my access was limited to regular research hours.

Marvin Taylor, founder of the Downtown Collection at Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University, which is where the David Wojnarowicz Papers archive resides, tells interviewer Emily Colucci that much of the work issuing from academia on archives serves merely to misrepresent the function of archives. Taylor’s main target is Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever, which he characterizes as “a useless piece of shit” (Colucci). In Archive Fever, which is more a response to the book Freud’s Moses than about archives per se, Derrida states that the word ‘archive’ is related closely to a default mode of reasoning that falsely promises total knowledge. According to the artist, critic, and theorist Allan Sekula:

Archival projects typically manifest a compulsive desire for completeness, a faith in the coherence imposed by the sheer quantity of acquisitions . . . Thus the archival perspective is close to that of a capitalist, a professional positivist, the bureaucrat, and the engineer—not to mention the connoisseur . . . (118).

The fact that both Derrida and Sekula trace the development of archives to cultural elites is interesting given that the word ‘archive’ is derived from the Greek archeion, which was the physical home of the chief magistrate or Archon who produced, preserved, and interpreted laws and records (Derrida 11-13). Hence, an archive consolidates the political power of those officials charged with its stewardship. The violence of the archive for Derrida is in the selection of materials, objects, and records for inclusion, which connects to Sekula’s insistence that archival ambitions are never neutral. An archive, for Taylor, “is nothing but the fossil evidence of experience . . . a stand-in for the absent body, because then you can talk about the fetish of the archival object” (Colucci). According to William Pietz the term fetish has “never been a component in a ‘discursive formation,’” as developed by Foucault in the Archaeology of Knowledge, with the “exception being the sexual fetish of twentieth-century medical-psychiatric discourse” (10). Taylor does not elaborate on the reason why it is useful to discuss the fetish status of archival objects and the enormous time researchers invest in archival pursuits, though he does praise Michel Foucault’s understanding of the archive as the conditions that enable meaning to occur in the first place. I can only speculate that Taylor means to imply there is an investment on the part of the researcher to select objects and texts contained in an archive that serve as symbolic resources that create or imply unity between the researcher and the artist or writer whose work is contained therein.

The research process unfurls slowly, mundanely, and according to convention-bound procedures as each folder or item is checked out and later checked in with the front desk staff. In order to access the David Wojnarowicz Papers, all qualified scholars and researchers must submit a reader’s application to a Fales Library and Special Collections archivist to describe the scope and purpose of the research (“Access”). Upon approval of the reader’s application, one must schedule an appointment in the reading room no less than forty-eight hours in advance of a visit. To enter New York University’s Bobst Library each day, a visiting researcher must interact with a security guard and show photo identification and a research pass that designates the duration of time for which Fales archivists have granted library privileges to that researcher. Finally, each day researchers with approved access and an appointment complete a manuscript request form, in consultation with the finding aid, which is an index of the materials housed in the Wojnarowicz Papers, and present that form to a staff member at the front desk of the reading room.

If archival materials are fetish objects for scholars and researchers, then perhaps this has more to do with the fact that the archival research process itself is premised upon the idea that only the initiated can gain access to or navigate through the many levels of bureaucracy and gate-keeping required. It almost goes without saying that being able to spend about seven hours a day, five days a week, as a researcher at New York University’s Bobst Library is itself an immense privilege and a significant expense, even if a researcher is fortunate enough to secure a research grant. Those artists and authors in the Downtown Collection are also an elite population, at least insofar as they occupy valuable and limited real estate or physical space in the Bobst.

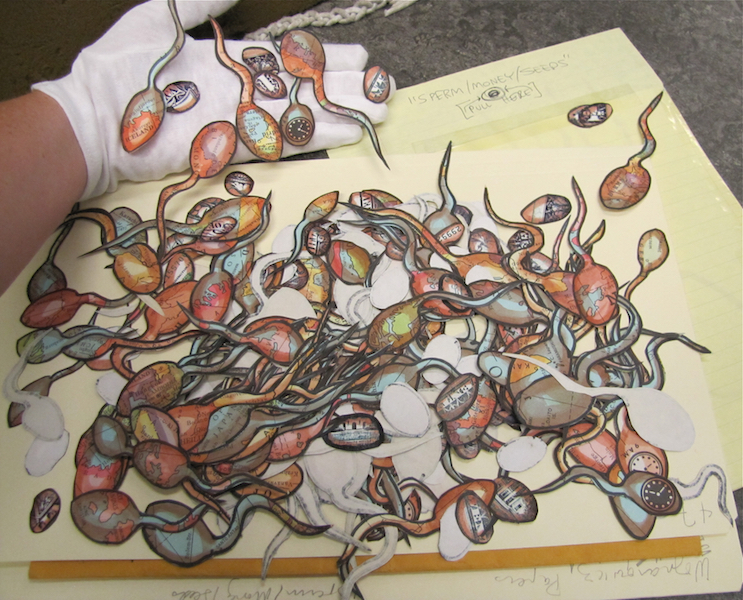

No doubt Taylor is well aware of the paperwork and procedures required to gain access to the collection, as he most certainly had a hand in establishing access policies and guidelines for patrons. In the absence of being able to have an actual conversation with David Wojnarowicz, which I very much desired and often imagined when I engaged his work, researchers who admire his work and want to touch the remnants of his life have little alternative than to make the trek to his archive. Had Taylor happened into the Fales reading room on the day my gloved hands touched Wojnarowicz’s envelope titled “Sperm, Money, Seeds,” and seen the joy on my face when I opened the envelope with the tab labeled “Pull Here,” he would have witnessed my immense excitement to caress and photograph myself caressing these artifacts. Despite the fact that I was required to submit a request for photograph reproduction form to a Fale’s archivist for approval, I choose to remember this moment, choreographed and directed by archival procedure, through a lens of delight and pleasure.

Photographic remix: Jessica Shumake’s hand with David Wojnarowicz’s “Sperm/Money/Seeds w/envelope.” Request for Photographic Reproduction granted by Brent W. Phillips.

The surprise and pleasure of having about one hundred cut out sperm—emblazoned with clock faces and made from photocopied maps and money—spill out of an envelope and onto the reading room table was immediate and immersive. I made a note in my journal that I could almost hear Wojnarowicz’s booming and resonant voice as he laughed with his artistic collaborator Marion Scemama and instructed her to “Cut the sperm!” (Scemama 128). The contents of the envelope may represent surplus labor on Scemama and Wojnarowicz’s part. These remnants could also be material representations of the artists’ excessive toil and the breakneck pace at which they worked together to prepare for the Sex Series (1988–89) exhibition, in what Mysoon Rizk designates as a phase in Wojnarowicz’s life when he worked with “‘a heightened sense’ of his own mortality” after learning his HIV-positive status. Direct contact with this artifact gave me vital confirmation of a narrative from Scemama that I read as I prepared in the months leading up to my visit to the Wojnarowicz Papers. As Scemama tells Sylvère Lotringer, in an interview:

[W]e were very excited about it [the Sex Series exhibition]. I was working with him night and day. He also did these paintings with maps with little sperms going all over. He would draw them and my job was to cut them out of maps. David loved to make me do those. He was always laughing and saying, ‘Cut the sperm! Cut the sperm!’ It was the most intense time of my relationship with him. (Scemama 128)

The handwritten note from Wojnarowicz on this artifact, which is an envelope made from yellow legal paper, with the instruction “Pull Here,” conveys his humor and reminds me of the last time I was the target of a practical joke from my friends’ son with his pack of gag gum that gave me a jolt of electricity.

I did not anticipate finding an envelope full of swimming sperm, nor did I expect to feel pulled in by this envelope and its contents, which may be leftover from a finished installation or suspended in time as part of an indefinitely postponed art project. I did not imagine finding what could very well be described as an interactive art installation, in a makeshift envelope, in the archive. The peculiar pull of this envelope is not something I can explain beyond saying that it involves those who touch it in a queer logic of desire to shape new meanings through association. Wojnarowicz’s “Sperm/Money/Seeds” instructs the researcher to “Pull Here” and in so doing symbolically confronts the person who tugs with the artist’s absence and a desire to conjure his presence. Wojnarowicz seems to say to tab pullers, “no, no, I’m not where you are lying in wait for me, but over here, laughing at you” (Foucault, Archaeology 17). In this moment I realized that the extension of an artist’s presence requires the researcher’s active participation, or at least discourages a more distanced and dispassionate analytical approach. Wojnarowicz’s “Sperm/Money/Seeds” communicates the importance of pleasure, play, and performance in engaging his archive in the here and now.

As I engaged with what artist and archivist E. G. Crichton calls Wojnarowicz’s “archival surrogate,” over the last several years, I did so with the full knowledge that Wojnarowicz has received almost no attention in rhetoric and composition, if textbooks in the field are a good measure of those who are considered significant. My aim, at least in part, is to create an opening for and a record of identification with queer antecedents in the here and now. Whether embraced by like-minded queer audiences or circulated among critics and public audiences more generally, what is most important is “David’s afterlife—his work getting used” and discussed (Carr, On Edge 309). Nothing pronounces the death of queer archives more effectively than no one caring about them. For my part, the tactile pleasure of engaging Wojnarowicz’s archive is bound up with a fleeting and yet charged encounter with his archival remains.

Archival research as a queer world-making practice takes the form of a visual art project for the New York artist and activist Emily Roysdon. Roydson restages Wojnarowicz’s photographic series Rimbaud in New York 1978–79, by donning a David Wojnarowicz mask. According to Roysdon, “performance and play,” are valuable “tactics” to claim space for queer life-worlds (Carlomusto and Roysdon 674). Douglas Crimp puts pressure on Roysdon’s reclamation of Manhattan’s Hudson River sex piers in her project titled Talk is Territorial (2007). Crimp describes Roysdon’s work as an interesting project for a woman given that the piers were a space of “recreations enjoyed almost exclusively by and between men” (Burton 201). For Roysdon, her identification with Wojnarowicz and masked reenactments of the Rimbaud in New York series led her to feel she has a stake in reimagining the West Side piers and the bodies that inhabited and circulated within that space.2

Roysdon restages Wojnarowicz’s well-known image of a masked Rimbaud injecting heroin. In Roysdon’s version of the photograph, which is part of her Untitled (David Wojnarowicz Project) (2001–2007), the hypodermic syringe goes not into the sitter’s vein at the inner elbow, but into the upper thigh (Roysdon). Roydson’s masked reinterpretation suggests a testosterone injection, which positions her series as a transgender and queer intervention. In an interview Roysdon describes her photographs in terms of her “desire to work with David, stitch myself into bed with him, turn myself into a fag. Yes, turn myself into a fag, allow my desire to move my body, change my body, to make something that gets me closer” (Carlomusto and Roysdon 673–74). When Roysdon discusses her motives for reimagining the West Side piers in Talk is Territorial, she extends similar concerns about queer lives and desires that remain largely invisible:

I am interested in reclaiming the piers as a much more diverse queer space where there were women . . . I am challenging both the idea that there were no women as well as the idea that most of the people there were white . . . I am interested in that story as much as I am in the photographs Alvin Baltrop shot there for twelve years, which were never exhibited in his lifetime. He would walk into galleries and his work would be refused . . . If you look at Alvin’s archive he has hundreds of pictures of people sitting out on the piers alone reading. There were all kinds of things going on there and I am more broadly interested in the fact that queers chose, and it was a choice, to go there. (Roysdon and Motta)

Roysdon centralizes the question of why queers who went to the piers for leisure reading and people watching were excluded from the prevailing account of the space as primarily occupied by white gay men who frequented it for public sex. When she challenges the excision of women, transgender people, and people of color through the lens of Alvin Baltrop’s camera, she constructs a nuanced understanding of the piers as a much more heterogeneous space.

It goes without saying that archives are not only places of pleasure and play in the here and now, but also complicated repositories for lost opportunities and missed connections. One way for curators and researchers to guard against overvaluing some artists and cultural workers is to be aware of the tendency to pay undue respect to some while slighting and undervaluing others. Osa Atoe, a musician, writer, and activist, like Roysdon, focuses on Baltrop’s lack of reception during his lifetime to reveal the impact of white privilege on the reception of his work.

According to his [Baltrop’s] close friend and assistant, Randal Wilcox, gay galleries were the most unreceptive to the late photographer’s work . . . ‘Many of these people doubted that Baltrop shot his own photographs; some implied or directly told him that he stole the work of a white photographer.’ . . . If Baltrop’s photographs had little value to those people during his life, why would they then begin to have value after his death? Why is a Black, poor, queer artist’s work only valuable after he is dead? (Atoe)

Atoe’s point, regarding the rush on the part of white gay gallery owners to collect the now-dead Baltrop’s photographs as commodities, is to acknowledge the potential for Baltrop’s photographs to lose their creative and critical vitality when they are offered for sale to the highest bidder. Atoe is also concerned that when Baltrop’s photographic archive is publicly and posthumously displayed, his photographs may lose their power to testify to the complexities involved in remembering the artist’s contribution to documenting the varied experiences and practices of pier-goers. For Atoe, it is crucial that curators display Baltrop’s photographs in ways that call attention to his lived experience of racial prejudice by foregrounding the fact that his labor went unrecognized and life’s work went uncelebrated during his lifetime.

Ethical engagement with and display of Baltrop’s archive must include attention to the embodied and material circumstances of his labor. Baltrop’s reception by curators and gallerists, all of whom refused to display his photographs while he still could have enjoyed the recognition, is too disgraceful to forget. Alongside Baltrop’s oeuvre, Wojnarowicz’s legacy and the attention it received during his lifetime feels hyperbolic and unjustified. One factor in Wojnarowicz’s access to the art world was the mentorship and encouragement he received from photographers Arthur Tress and Peter Hujar (Carr, Fire 96). In the absence of mentors who could have opened doors to gallery exhibitions and helped Baltrop advocate for the value of his work, his art went unrecognized and in some cases was outright stolen without attribution or compensation (Atoe).

When we frame archival research as a queer practice, in Heather Love’s words, we can aim to “do justice to the difficulties of queer experience” by developing a “politics of the past” (21). What are archives, then, if not spaces to forge new associations between the past and the present for the here and now? Perhaps the biggest implication for the composition classroom is the creation of opportunities for students to experience how archives are rhetorical, material, and affective spaces. I have designed and taught composition courses in which my students worked with special collections archivists to practice research on and writing about cultural artifacts. Students not only wrote museum labels for artifacts to provide special collections visitors with information about the objects and images in an exhibit, but also engaged in primary archival research on student scrapbooks from the early twentieth century and other historical sources. Indeed archives and the sources of information housed within them both preserve the past and help those who engage them become writers and scholars in the process.

Foucault’s archival findings at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, which he describes in his essay “Lives of Infamous Men,” reveal one queer and poetic method I recommend for teacher-scholars who desire to facilitate their students’ engagement with archival kindred spirits. His research practice has a serendipitous quality akin to a kind of archival cruising: “Nothing made it likely for them to emerge from the shadows, they instead of others, with their lives and their sorrows” (Foucault, “Lives” 163). Foucault’s conjuring of various individuals, who otherwise would have languished in dust and darkness without a trace, is a random process with the exception of a few rules he sets for himself. Chief among these rules is the restriction that the archival figure to whom he attends must “form part of the dramaturgy of the real” (Foucault, “Lives” 160). The vagabond monks, cruel women, sodomites, and oddballs to whom Foucault is most drawn are those who touch him in ways he says he “might have trouble justifying” (“Lives” 157). I believe that Foucault’s attachment to these obscure figures in the archive, specifically through his disclosure of how they make him feel, combined with his ethical recognition of the dignity of their lives, enables him to bear witness to lives constrained, lives worthy of engaging, if only by forging meaning in its equally plausible absence.

Notes

1I thank The Writing Instructor special issue editors Aneil Rallin, Trixie Smith, and Rob Koch for their valuable suggestions.

2I thank José Esteban Muñoz for recommending Roysdon’s work to me during his visit for the Miranda Joseph Endowed Speakers Series at the University of Arizona’s Institute for LGBT Studies in Mar. 2012.

Works Cited

“Access.” nyu.edu/library/bobst/research/fales/abouttest.html. Fales Library & Special Collections. Web. June 11, 2011.

Alexander, Jonathan, and Jacqueline Rhodes. “Queer Rhetoric and the Pleasures of the Archive.” Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture 13 (2012). n.p. Web. Jan. 22, 2013.

Atoe, Osa. “Alvin Baltrop: Colorlines News for Action.” Applied Research Center: Racial Justice through Media, Research and Leadership Development. 24 March 2009.n.p. Web. Sept. 17, 2012.

Burton, Johanna. “New York, Beside Itself.” Mixed Use, Manhattan: Photography and Related Practices, 1970s to the Present. Ed. Lynne Cooke, Douglas Crimp, and Kristin Poor. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2010. 187–227. Print.

Carlomusto, Jean, and Emily Roysdon. “Radiant Spaces: An Introduction to Emily Roysdon’s Photograph Series Untitled.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 10.4 (2004): 671–79. Print.

Carr, Cynthia. Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz. New York: Bloomsbury, 2012. Print.

—. On Edge: Performance at the End of the Twentieth Century. New Hampshire: UP of New England, 1993. Print.

—. “Portrait in Twenty-three Rounds” Fever: The Art of David Wojnarowicz. Ed.Amy Scholder. New York: Rizzoli, 1998. 69-89. Print.

Colucci, Emily. “The Dirty Scene of Downtown New York: An Interview with Marvin Taylor.” Hyperallergic: Sensitive to Art & Its Discontents. 10 Aug. 2012. n.p. Web. May 20, 2013.

Crichton, E. G. “Lineage: Matchmaking in the Archive, A Collaboration between the Living and the Dead.” College Art Association Annual Conference. Chicago, IL. February 2010. Unpublished Manuscript. Web. May 12, 2013.

Danbolt, Mathias. “Touching History: Archival Relations in Queer Art and Theory.” Lost and Found: Queerying the Archive. Eds. Mathias Danbolt, Jane Rowley, and Louise Wolthers. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Contemporary Art Center, 2010. 27–45. Print.

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Chicago: U Chicago P, 1998. Print.

Faunce, Rob. “Teaching Querelle in the Composition Classroom.” Pedagogy 12.2 (2012): 343–52. Print.

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge & The Discourse on Language. New York: Tavistock Publications Ltd., 1972. Print.

—. “Lives of Infamous Men.” Power: The Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984, Vol. 3. Ed. James D. Faubion. Trans. Robert Hurley. New York: New Press, 2000. 157–75. Print.

Love, Heather. Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2009. Print.

Morris, Charles E., III, and K. J. Rawson. “Queer Archives/Archival Queers.” Theorizing Histories of Rhetoric. Ed. Michelle Ballif. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2013. 77–89. Print.

Pietz, William. “The Problem of the Fetish, I.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 9 (1985) 5–17. Print.

Rallin, Aneil. “Taming Queer.” Symplokē 13 (2005): 152–57. Print.

Rizk, Mysoon. Nature, Death, and Spirituality in the Work of David Wojnarowicz. Diss U of Illinois, 1997. Print.

Roysdon, Emily. “Untitled (David Wojnarowicz Project) 2001–2007.” emilyroysdon.com. Web. Mar. 28, 2012.

Roysdon, Emily, and Carlos Motta. “An Interview with Emily Roysdon.” wewhofeeldifferently.info. We Who Feel Differently: Interview by Carlos Motta,

Apr. 15, 2011. Web. Jan. 16, 2012.

Sekula, Allan. “Reading an Archive.” Blasted Allegories: An Anthology of Writings by Contemporary Artists. Ed. Brian Wallis. New York: MIT P, 1987. 114–27. Print.

Scemama, Marion. “Marion Scemama.” David Wojnarowicz: A Definitive History of Five or Six Years.Ed. Hedi El Kholti, Chris Kraus, and Justin Cavin. Interview by Sylvère Lotringer. New York: Semiotext(e), 2006. 122–41. Print.

Wojnarowicz, David. Rimbaud in New York 1978–79. Ed. Andrew Roth. New Haven, CT: PPP Editions, 2004. Print.

—. “Sperm/Money/Seeds w/envelope” in Series XI, Box 19, Folder 21, David Wojnarowicz Papers, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University, undated. Print.